The late Kalaaleq artist’s works in Arctic Hysteria at KW Berlin both preempted and inaugurated a new era for Kalaallit art

In 1995, in the Explorers Club, New York, a private club for exploration frequented by scientists and a wealthy elite, the Kalaaleq-Danish artist Pia Arke stumbled upon a file titled ‘Pibloctoq – Arctic Hysteria’. Inside was a photograph showing a nude Inuit woman seized by white male colonisers. Unfamiliar with the term, Arke found it to be a supposed mental condition that explorers had diagnosed in Inuit women; its symptoms including fits of rage, unpredictability and an insensitivity to the cold. When Arke, who based a large part of her practice on archival research, requested permission to use the picture, her application was denied. Instead, she proceeded to recreate it in Arctic Hysteria, a 1996 videowork that also gives name to the current exhibition at the KW Institute in Berlin, the largest Pia Arke solo exhibition outside of Scandinavia and Kalaallit Nunaat (what settlers later called Greenland).

In the video, we catch a glimpse of an almost bare room, before the camera zooms in on a black-and-white photograph of a snow-covered coastline. Initially, we see hands, then the artist’s full body, unclothed, crawling on top of the large outspread print. She moves gently at first, stroking the print, smelling it. Exploring the coastline, she seems to search for her own place in the scenery. However, her delicate, almost erotic movements turn increasingly restless: she squirms on top of the panorama, twisting and turning, never stationary. Eventually she makes a tear, a cautious one. Her tearing becomes increasingly ferocious, before finally ripping the representation of the landscape to shreds all around her in a perfect mess.

Born in 1958 on the northeastern coast of Kalaallit Nunaat to a Danish father and a Greenlandic mother, Arke described herself as having been born into a silence. A silence surrounding the ties between her homelands, and a silence that even today prevails. Kalaallit Nunaat has been claimed as Danish territory since 1814, yet Kalaallit citizens only became Danish citizens in 1953. Granted home rule in 1979, Kalaallit Nunaat’s autonomy was expanded in 2008. Still, Denmark remains in charge of foreign affairs and monetary policy, though the countries’ interrelation takes up almost no space in Danish public discourse.

Looking back on my schoolyears in 2000s suburban Copenhagen, I can only recall a single time Kalaallit Nunaat featured in a lesson: a geography class where we were taught that if you added its territory to ours, Denmark would count among the largest countries on the planet. Growing up I knew nothing about Kalaallit Nunaat’s history. I knew nothing of the 1952–53 forced relocation of the residents of the city Thule by the Danish government in order to clear space for a US air base; nor of the hundreds of children who, from the 1950s to the 70s, were adopted under dubious circumstances by Danish families; nor of the thousands of girls, some as young as thirteen, who, in the 1960s, for the sake of lowering birth rates and costs to schools and welfare schemes, had birth control implanted by Danish doctors without their knowledge or consent.

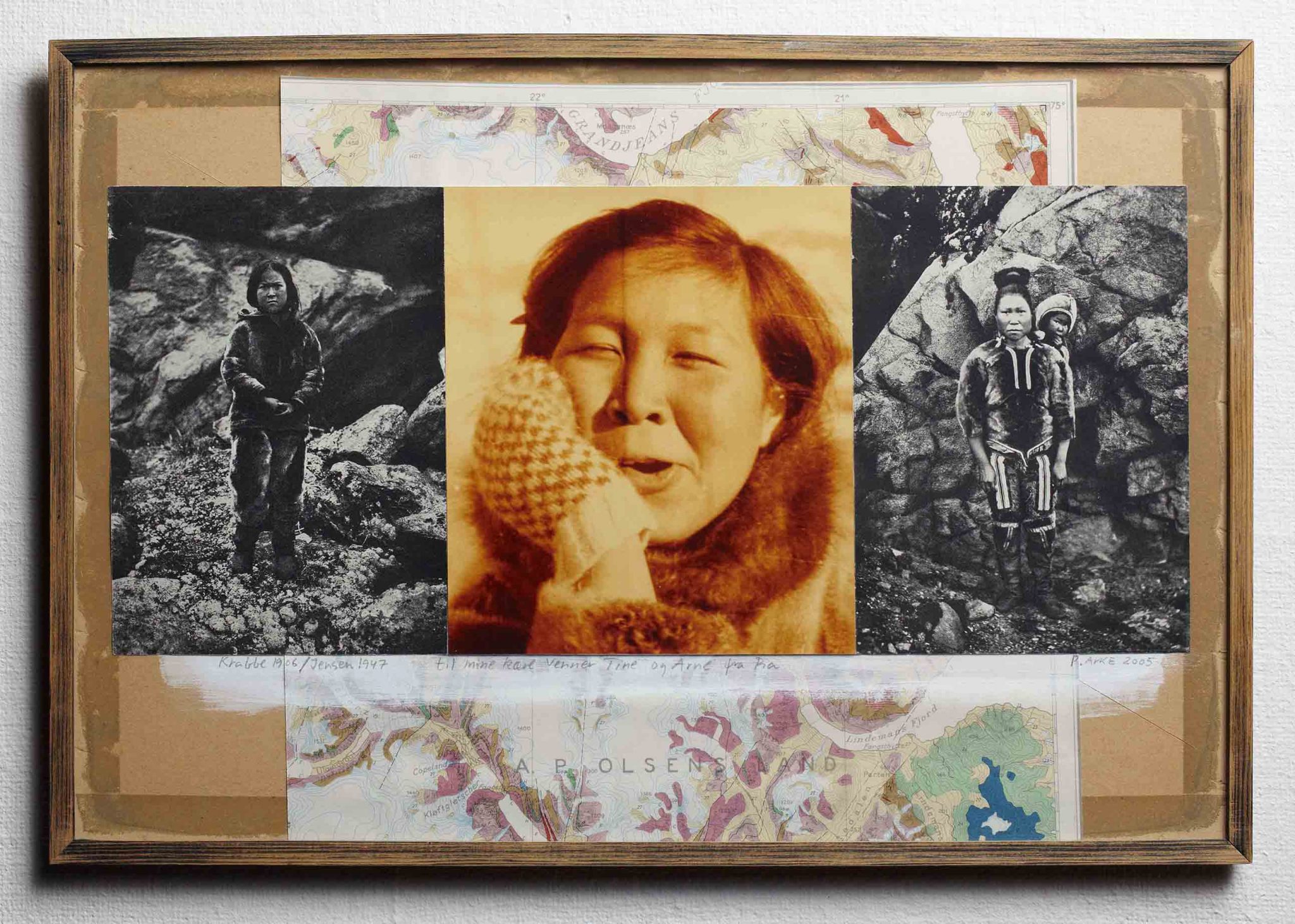

Spread out over two floors and featuring over a hundred works, the KW exhibition demonstrates the range of Arke’s short but prolific career (she died from cancer in 2007 at the age of forty-eight), spanning photography, performance, text, collage, sculpture and video. There is the performance in Arctic Hysteria (1996); the tender, yet brutally honest photographs such as of Arke’s friend Susanne with her upper body uncovered, revealing a removed breast, a prosthesis resting on her leg, in the series Perlustrations I–XI (1994); as well as the collage series Legend I–V (1999), where Arke affixed old explorers’ maps with photos of Kalaallit people, including her young mother, and ornamented them with oats, coffee, rice, flour, tobacco and sugar, colonial goods imported to the Danish colonies in Kalaallit Nunaat after 1837.

Originally accepted into the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen in 1987, Arke was supposed to study painting, but abandoned it to pursue photography. The exhibition text tells us that she would often describe herself as a mongrel, due to her Danish-Kalaallit background. Indeed, Arke saw her shift away from painting as natural, considering that photography too could be said to be the mongrel of the art disciplines. She wanted to create art that was neither Danish nor Kalaallit, challenging the notion of art as adhering or relating to nation-states. For this purpose, she came up with what she called an ‘Ethno-Aesthetic’, a term reappropriated from Danish art historians who employed it to describe Kalaallit art. As the writer Stefan Jonsson wrote in 2021 for a publication on her work by the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, ‘The concept testified on the one hand to how cultural power relations had placed her on the periphery as an ethnic, on the other hand to how she now used her imposed ethnic identity as a starting point for an aesthetic critique of the norms that expected her to cultivate her “Greenlandness”, for example by painting polar bears.’ Rather, Arke elected, in full earnestness and playfully, to paint camels in snowscapes.

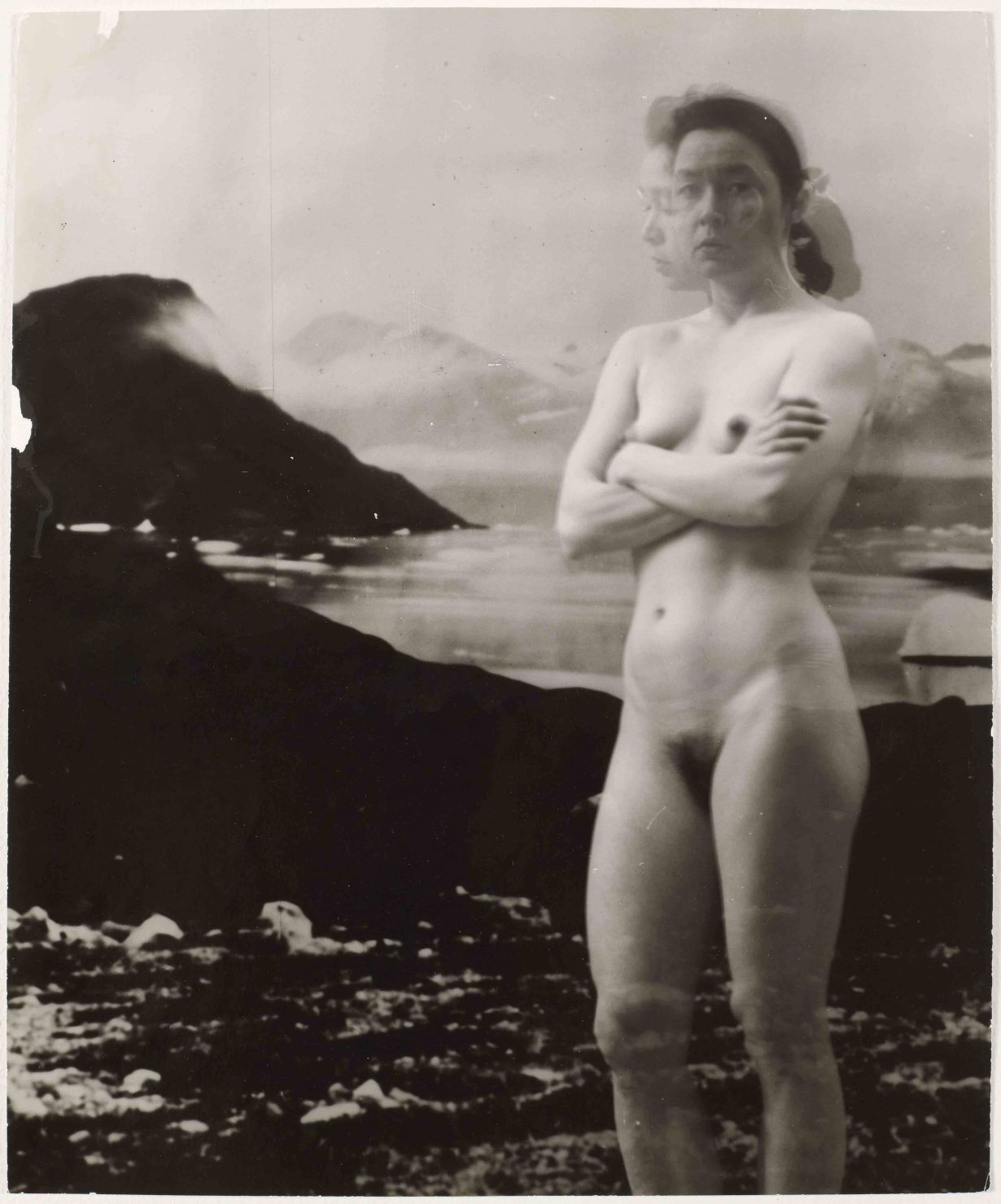

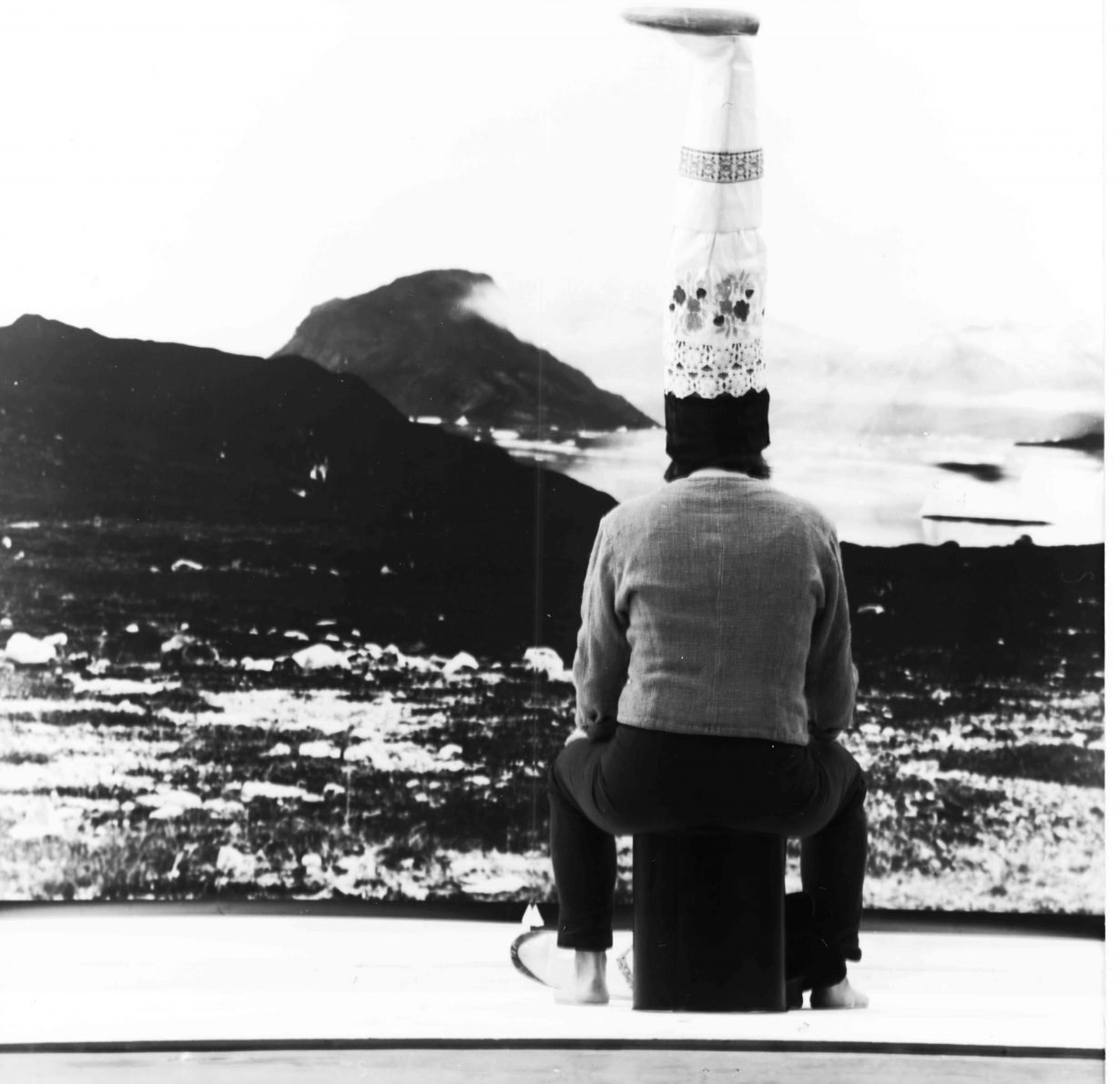

Ever a restless experimentalist, Arke constructed her own camera obscura, present at the centre of the KW exhibition. The size of a small shed, with white walls and a vault to climb in through, the camera itself was built to fit a human being, merging artist and apparatus. Once, Arke managed to ship it to Kalaallit Nunaat, where she took a panorama of the Nuugaarsuk coastline. This image would be part of several important works: either with paint blots or scribblings on it; or with Arke posing or performing in front of it, such as in Self-Portrait (1992), a double exposure nude self-portrait before a photostat of the panorama, in which the artist is facing the camera while also looking away; or as the backdrop for a photo, Untitled (Put your kamik on your head so everyone can see where you come from) (1993), where she is seated with her back to the camera, wearing a traditional Inuit boot on her head, the title instilling a grim humour to posing as a disobedient colonial subject. In many of her works is a sharp and funny critique of the expectancy of ‘Greenlandic’ artists to showcase ‘Greenlandness’.

In this year’s Venice Biennale at the Danish national pavilion, ‘Kalaallit Nunaat’ is spelled over the word ‘Danmark’. Inside is an exhibition by Inuuteq Storch, a photographer drawing heavily on archival material, and the first ever Kalaaleq artist to represent Denmark. Sadly, Arke was not alive to witness it. But her fingerprints are there to be found today. Greenlandic artist Jessie Kleemann describes her (in the publication accompanying the Louisiana show) as a pioneer: ‘She put into words what so many of us felt: that the colonial gaze still affected us’. Moreover, breaks in the silence have started to emerge. Following last year’s controversy surrounding politician Aki Matilda Høgh-Dam’s insistence on speaking Kalaallisut (or Greenlandic) in government debates, the right to speak Kalaallisut and Faroese in the Danish parliament has since been enshrined in law. Additionally, Denmark and Kalaallit Nunaat have agreed on an investigation of the countries’ relation, and just last month a number of illegally adopted children sued the Danish state. It is this context that underscores the vital timing of the exhibition at KW.

Arke was Kalaaleq and Danish, though also neither. In her art she searched for a third space, and from this place she created a language for postcolonial artmaking that was at once critical, emotionally charged, humorous, honest and optimistic. Perhaps more than any work in the Berlin show, the black-and-white photoseries titled The Three Graces (1993), referencing a motif from Greek mythology, demonstrates her method: her focus on the female Inuit body, criticism of Western art history and its patronising views of Kalaallit art, and the use of performance. Posing in front of the photostat of the Nuugaarsuk shoreline, the three women – Arke, a friend and Arke’s cousin – stare straight down the lens, serious-looking, united, as if protective of the land. In another photo, they carry stereotypical Kalaallit objects, such as an Inuit mask and a sled dog whip. Before, lastly, in the final photo, turning their backs to the outside gaze, seemingly merging with the landscape.

Arctic Hysteria at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, through 20 October