Jonathan Griffin on how to read the work of an artist’s short career, and life

Facts and suppositions about Ree Morton’s life might not be so integral to our reading of her art if she hadn’t died in 1977, aged forty, having started late, leaving behind just six or so years of work: a compact oeuvre of sculpture, drawing and installation that acquires an almost unbearable poignancy when framed by the knowledge of its sudden ending.

Nowhere in The Plant That Heals May Also Poison – the survey that originated at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, in 2019, and now concludes at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles – do we learn how Morton died. Even in the catalogue, presumably to avoid sensationalising her narrative, it’s not revealed until page 64 that she died after being injured in a car crash, then never mentioned again.

As with any artist who died young, Morton’s narrative is burdened by pathos; in the loosely chronological hang at the ICA LA, the work accrues a gathering sense of doom. The earliest works, such as the wall-mounted Wood Drawings (1971) made from scrap wood, pencil and felt-tip, combine the expansiveness of mapmaking with the humility and simplicity of Agnes Martin’s drawings. Over time, text and appropriated content enter the work, and along with it hints of Morton’s wry humour and sharp sense of irony. There’s no escaping the feeling that a sickly presence was growing inside the work, despite its often upbeat aspect: her preference for pastel colours, always slightly muddy; the toxic-looking, malleable plastic known as Celastic that became her trademark material; her motifs of drooping, soggy bows and thick-petalled flowers; her use of weak yellow lightbulbs, forever on.

In fact, art for Morton was a route to self-realisation, celebration and joy. In exhibition notes, ICA Philadelphia curator Kate Kraczon and ICA LA curator Jamillah James handle Morton’s story with sensitivity, detailing the revelatory evening drawing classes she attended during the 1960s while living in Jacksonville, Florida, with her three children, and what they describe as ‘the happiest summer of her life’, spent with them in Newfoundland, Canada, and which inspired the maplike pencil Newfoundland Drawings and the wood, canvas and acrylic sculpture Souvenir Piece (both 1973).

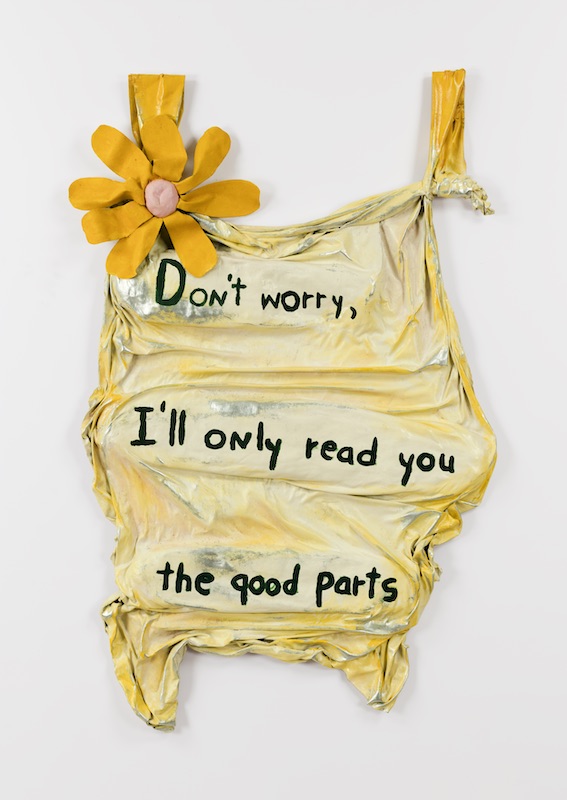

As her work developed, Morton increasingly exploited the visual clichés attached to her role as a woman and mother. In a typed funding application from 1976 (found in one of two vitrines of photographs and print ephemera), she describes wryly her ‘classic housewife / mother with unsympathetic husband situation’, noting that her children are now living with their father while she concentrates on her work in New York City – ‘an exciting phase of ripening ideas and images’. The corner installation For Kate (1976) includes two twisting Celastic streamers that loosely bracket a smattering of sticky-looking sculpted roses and a painting of more roses that resembles an old-fashioned tea tray (the title possibly refers to Morton’s grandmother). In Don’t worry, I’ll only read you the good parts (1975) – perhaps the most heartbreaking work in the show – the titular promise is painted on a wrinkled sheet of Celastic that resembles a drying animal hide, accompanied by a cartoonish yellow flower. It is a promise that, though lovingly sincere, seems wrapped in the knowledge of its inadequacy.

Morton paid tribute to the people, places and things she loved in artworks that are, in many cases, rather hard to love. It was almost as if she was testing how far deep and true sentiment could carry forms that were not – and are still not – conventionally beautiful. It takes time to fall in love with the things Morton made, and that seems to be how the artist wanted it.

Ree Morton, The Plant That Heals May Also Poison, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 16 February – 14 June 2020

From the April 2020 issue of ArtReview