From a recent wave of exhibitions and publications, two broad factors have emerged to explain the critical neglect of postwar art in California: the importance of craft, new materials and techniques often obscured intellectual rigour, and a regime of censorship and repression was carried out by district attorneys and police departments (particularly in Southern California) who saw themselves as cultural enforcers. Falling at the intersection of these factors is this show’s striking suite of nine lithographic prints produced at the end of 1963 by Connor Everts, titled Studies in Desperation. Though charged with an existential angst that was, by 1963, losing favour to a cooler sensibility, Everts’s lithographs leverage the affective power of the human body as well as the ability of print techniques to convey the psychic and political turmoil of the era beyond the relative intimacy of drawing and painting.

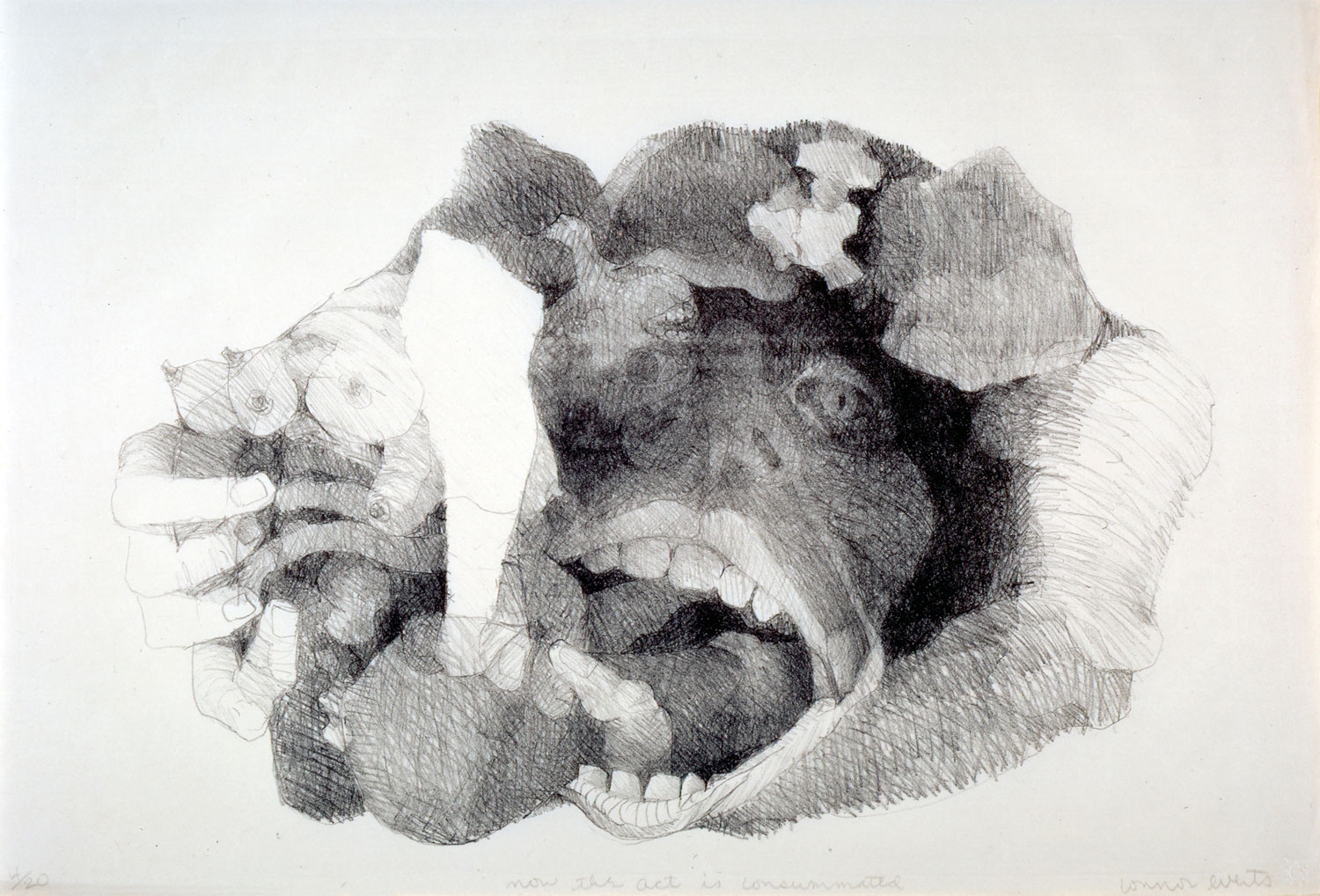

Everts said of his suite, ‘I was thinking about the state of the world and the view of the world from the womb. What if someone looked out from the womb and decided not to be born until it was a better world?’ These comments capture the social implications of Everts’s embodied vision during the era of civil rights, the Kennedy assassination and the onset of the Vietnam War. From the colophon, one Janus- faced figure splits into two, who then grapple and merge with each other until both male and female body parts seem to be cannibalised by a giant face in a print titled Now the Act Is Consummated. In the prints that follow, bones, faces, masks and genitals comingle and contort in a shallow space, offset from one another by dramatic lights and volumetric crosshatching and ribbing. In the final two prints, Dependency, Love of the Lost? and Adjustment Alone as Always, the figures do indeed seem to reinhabit an ovular womb that is not a refuge but repository for a fractured anatomy.

Everts’s images are less obscene than they are grotesque, which is why it is somewhat surprising that they drew obscenity charges from the Los Angeles District Attorney when they were first exhibited at the Zora Gallery in 1964. Coming between the prosecutions of Wallace Berman and Edward Kienholz, Everts’s trial galvanised the community that was then centred on the Chouinard Art Institute (where Everts taught), the Tamarind lithography studio and the Pasadena Art Museum, where he had a solo exhibition of drawings in 1960 (and which became the Norton Simon in 1975). Though he was eventually acquitted in 1965, Everts suffered a beating from police the following year that damaged the nerves in his drawing hand. One wonders if his dissemination of such a raw, personal vision as a lithographic multiple played a role in provoking law enforcement reactionaries; in any case, their efforts seem only to have confirmed the artistic integrity of a medium emerging from commercial associations, and the Norton Simon is a fitting place for Everts’s contribution to receive its due.

This article was first published in the April 2013 issue.