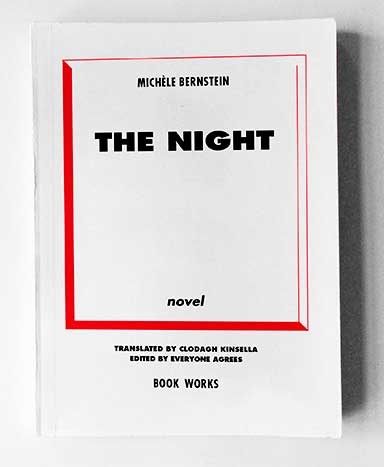

Michèle Bernstein and her first husband Guy Debord have long been figures of fascination for those grooved by the Lettrist and Situationist movements. But interest in the two novels Bernstein wrote half a century ago has grown because the story each tells appears to provide insights into her open marriage to Debord. The second of them, The Night, published in France in 1961, has now been translated into English.

It tells the same story as Bernstein’s first book, All the King’s Horses (published in France a year earlier, translated into English in 2008): the tangled but loving relationships of Gilles, Geneviève, Carole and Bertrand. All the King’s Horses was written in the style of a popular romance, whereas The Night is billed as parodying the nouveau roman. However, Bernstein was too hung up on the strategies a young wife uses to maintain her husband’s love to write a successful parody of the format – or at least in the style of its best-known protagonist, Alain Robbe-Grillet, who used pseudo-objective descriptions to reveal human subjectivity. Bernstein makes no attempt to do this and her burlesque goes little further than using an apparently random and nonchronological ordering of events. What Bernstein does well is produce a paradigmatic example of Lettrist détournement – the hijacking of preexisting cultural material and its redeployment to revolutionary ends. She very successfully incorporates elements from her own life, various films and other people’s books into The Night.

Bernstein has a great sense of humour and sends up the scene to which she belonged in ways it would be difficult to imagine some of its male members doing (particularly those who, like Bernstein, were native French speakers). For example, a silly but amusing parody of the COBRA painting movement: ‘Someone will… explain that their host is none other than the founder of the Python movement, already famous in certain avant-garde circles, and that Python, as few people know, represents the initials of: Paris, Yokohama, Tunis, Hamburg, Oslo and Namur; Ole’s group having members in these six towns…’ . (COBRA, of course, took its name from the initials of Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam.)

Bernstein is clearly very much in love with her husband, Debord (Gilles in the book): ‘Gilles once created, in some art form or another, such a systematically negative masterpiece that he now thought he had the right to ten years of peace if poverty didn’t take him by the throat.’ I assume the ‘masterpiece’ in question is Debord’s 1952 film Howlings in Favour of de Sade, which I view as the high point of his oeuvre. No doubt Debord fanboys will read sentences like the one I’ve just quoted and see them as fostering the untenable anarchist myth of their hero managing to live differently within capitalist society, although the actual message of the book seems to be the complete opposite. Gilles/Debord is/was supported by his wife in both the book and real life, and The Night is probably the most honest account of the banality of everyday life within the Lettrist International precisely because of its status as fiction, which allows Bernstein to present her material both poetically and prosaically.

One strand of The Night concerns a walk, or drift, around Paris on 22 April 1957 during the final days of the Lettrist International – the Situationist International was founded a few months later. In After the Night, a détournement of Bernstein’s book by the anonymous London–New York-based collective Everyone Agrees, this drift is transposed to contemporary London. The text of After the Night was finalised for print on 26 April 2013, and the book references events that took place just a few weeks before it was published. Like the original novel, the rewritten version includes much appropriated material, including this from a piece I wrote about Wu Ming for the April 2013 issue of ArtReview: ‘Strong coffee is a common addiction in British counterculture.’ Despite the obscurity of certain references, Michele Bernstein says After the Night made her laugh out loud. The rewrite has genuinely funny moments, but Bernstein’s mirth also stemmed from the seriousness with which Everyone Agrees treats The Night – never the author’s intention.

This review originally appeared in the September 2013 issue