If all the pearl-clutching pundits could leave their prejudices at the door, perhaps they’d realise that the ICA exhibition Decriminalised Futures is an urgent and vital call to action

‘Hell’s Angels and young men with multi-coloured hair, lipstick and nail varnish.’ ‘An excuse for exhibitionism by every crank, queer, squint and ass in the business.’ ‘Porn-pop art show! Distasteful and unartistic!’ These were just some of the responses across the national press when London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts held a sex work-themed exhibition, titled simply Prostitution, in 1976. The Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn branded the event a ‘sickening outrage […] Obscene. Evil.’ He proclaimed in parliament that ‘public money is being wasted here to destroy the morality of our society,’ and described exhibition organisers COUM Transmissions (led by Genesis P-Orridge and Cosey Fanni Tutti) as ‘the wreckers of civilisation.’ Now, nearly 50 years later, the ICA is hosting another show that delves into sex worker experiences, Decriminalised Futures, people of all genders with multi-coloured hair, lipstick and nail varnish throng the Mall, and…are people still outraged?

Well, unfortunately but predictably, you don’t have to look far for ’70s retro indignation. There’s an echo of Fairbairn’s disparaging tone in The Telegraph review’s headline: ‘an aesthetically and morally bankrupt hymn to ‘sex work’’ (those derisive quotation marks implying the reviewer – philosopher Nina Power – perhaps prefers the outdated language used provocatively by the former ICA show’s title?) Similarly, while it may be lacking the vintage frisson of voyeurism, the Daily Mail’s recent headline – ‘Contemporary art gallery that received £2.7 million in public funding is staging an exhibition celebrating sex workers’ – certainly smacks of the Daily Express’s 1976 scarehead: ‘State aid for Cosey’s travelling sex troupe.’ On this evidence it would seem little has changed in half a century – ‘our’ society and ‘our’ civilisation and ‘our’ tax money supposedly still under threat from immoral forces, and conservatives still getting rubbed up the wrong way by any public acknowledgement of the sex industry. Money and morality: a tale as old as time; older even than ‘the oldest profession’.

If all the pearl-clutching pundits could leave their prejudices at the door, perhaps they’d realise that the exhibition currently being presented at the ICA is not only urgent and vital, but also, in fact, a world away from COUM Transmissions’ controversial show. Featuring extreme performances, pornographic photographs, and props that ranged from a rusted knife to bottles of blood, Prostitution’s heady blend of ’70s punk and art was designed precisely to shock and scandalise – to stick two fingers up to the establishment. In this context, sex work was used as a metaphor, both for a generalised idea of ‘the subversive’ and for the work of the artist within a commercial art market. The poster proclaimed, ‘everything in the show is for sale at a price, even the people,’ and P-Orridge explicitly asserted the exhibition was about how the artist has to sell themselves and their work, declaring ‘one is debasing oneself by selling.’

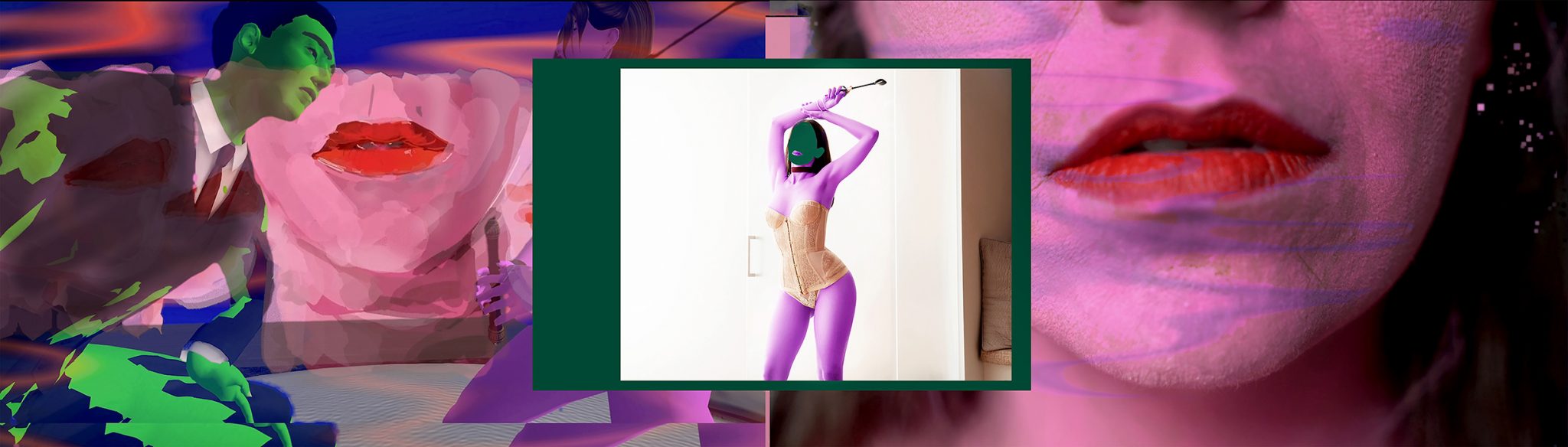

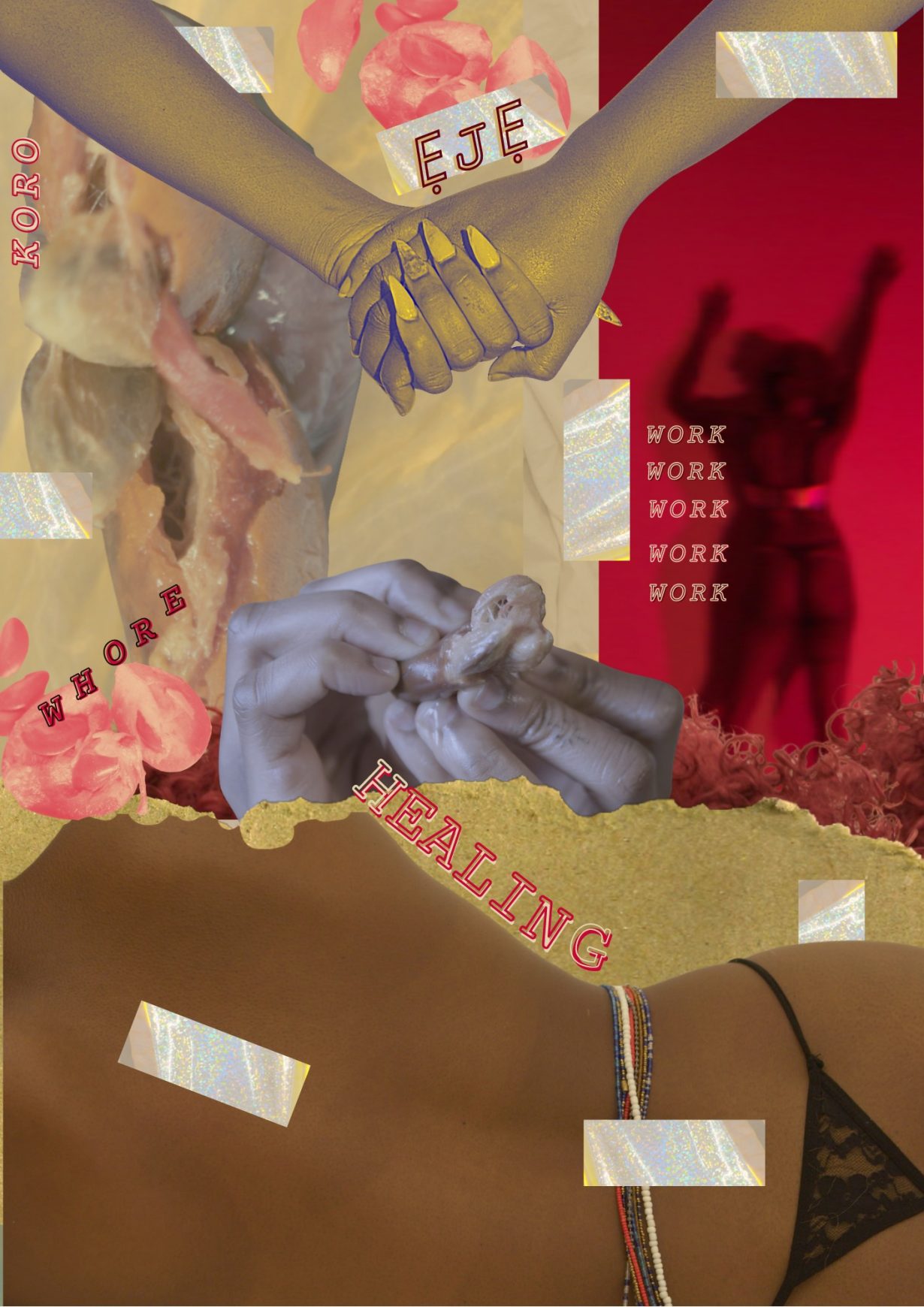

But while the relationship between sex work, art work, and other forms of labour under capitalism is, of course, crucial to Decriminalised Futures, the artists in this show start from a different premise and perspective. Instead of using sex work as a symbol for the indignity – the ‘debasement’ – of all paid labour, here sex work is approached as a lived reality, and a possible source of inspiration in the collective struggle for workers’ rights; for security and dignity. Certainly, the exhibition is polemical, explicit and activist, and features whips and bejewelled dildos. And certainly it aims to rattle some cages (it would be exceedingly strange for a show about decriminalisation and policing not to). But where Prostitution revolved around extremity and violence, Decriminalised Futures centres care, justice and solidarity. Some things have changed in the last half century; Fairbairn’s remarks were always pretty laughable, but P-Orridge’s comments about ‘debasing oneself’ now also seem simplistic, reductive and naive, stemming from an outsider’s gaze on the sex industry. The ‘outsider’s gaze’ is, of course, always potentially also the client’s gaze, and, as Yarli Allison and Letizia Miro’s sublime semi-fictional documentary declares, This is Not for Clients (2021). Instead, the exhibition’s co-curators Yves Sanglante and Elio Sea say, ‘this exhibition is a testament to what can be created when we take politicised sex worker organising as our starting point.’

Seeds, soft fruits, soft furnishings. A crutch, hairbrushes, an embroidered lipstick on an embroidered nightstand. Eating. Dancing. Holding a child’s hand. Many of the artworks in Decriminalised Futures – all of which were selected after an open call to address global sex worker experiences – are deliberately tender, tactile, and domestic; nuanced reflections on space and intimacy. The show opens with Aisha Mirza’s brilliantly titled installation, the best dick i ever had was a thumb & good intentions (2022), which features the artist’s zines, plants and high-heels, in an almost-bedroom space. A mirror hangs on the wall, with a row of whips and paddles and the phrase ‘i am a dominatrix, or, i believe you completely’ above it. Aside from complicating conventional notions of domination, comfort and care, what’s obviously at stake here is solidarity and complicity. The viewer is invited in, asked to look in the mirror, to roleplay. Who are you in that space? Your gaze, your body, your subjectivity is never neutral, the exhibition stresses. As Cory Cocktail’s choose-your-own-adventure dystopian videogame aičhimani (2020) prompts, what will you do next? Or, as one of Tobi Adebajo’s mesmerising films asks, ‘What are you ACTUALLY doing here?’

This constant refrain – this call to recognise your position, this call to action – is the lifeblood of the exhibition, and what keeps the softness and tenderness in the artworks from ever tipping into sentiment or cliche. This might be unsurprising, given the organisations behind Decriminalised Futures are the Sex Worker Advocacy and Resistance Movement (SWARM) and Arika, the political arts organisation that supports projects addressing social change, but it is still remarkably refreshing to have an art space so explicitly take a progressive political stance. On the introductory wall: ‘Sex work is work; Rights not rescue; Nothing about us without us; No bad whores, just bad laws; Decriminalisation now; Someone you love is a sex worker.’ Total decriminalisation is, quite literally, only the starting point – one element of an interconnected and intersectional social justice movement led by marginalised people for marginalised people (but also, of course, for everyone, because that is what solidarity and collective action means).

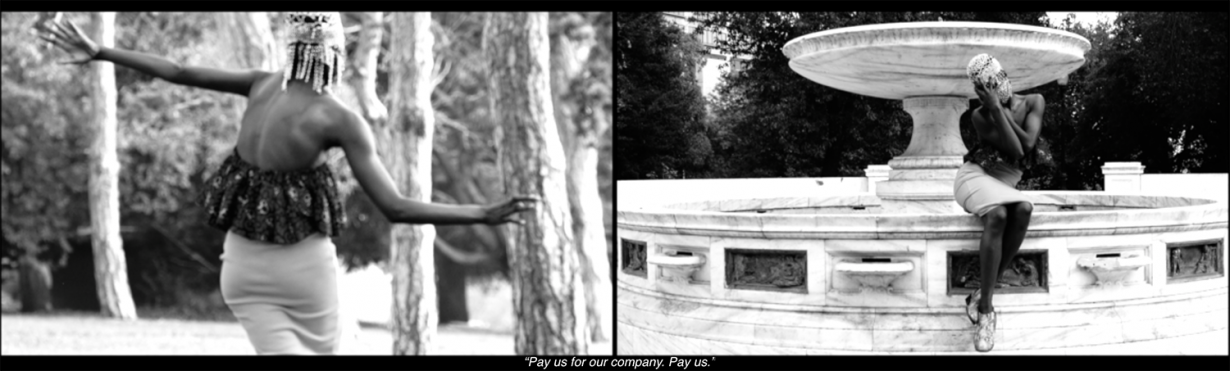

This isn’t to suggest there isn’t darkness, and pain, and anger on display – any exhibition concerning oppression and marginalisation would be remiss not to include these negative affects. Danica Uskert and Annie Mok’s graphic novel Unsustainable (2020) is particularly heart-wrenching, and Yarli Allison and Letizia Miro’s collaborative film – a hyperreal narrative that transmutes Miro’s real-life experiences into a fantasy realm – might be visually lush, but is incisive about the precarity that sex workers face. But this ability to blend economic and political arguments with both melancholy and rage, and hope, joy, and beauty, is ultimately, the exhibition’s biggest strength. Instead of a one-note portrayal – of either glamorization or victimisation – here is multiplicity and a depth of thought and emotion. Upstairs, over Chi Chi and May May’s lush monochrome film of women brushing their hair and dancing in the open air (Stone Dove, 2021), the lyrics ask: ‘why is it never enough? I think I’m more than enough.’ Downstairs, the voiceover to Adebajo’s film rises to a shout: ‘I should not have to prove myself to you. I should not have to prove myself to you! Come on. Let’s overthrow capitalism. Capitalism. DECRIMINALISE. DECRIMINALISE RIGHT NOW.’

What the artists gathered in Decriminalised Futures show is that it’s only when shame, stigma and stereotypes are dismantled – when prejudices are left at the door – that real questions can begin to be posed. What kind of future do you want? What might be possible? What’s necessary? What will you do next? What’s the opposite of an ‘morally bankrupt hymn’? A morally secure cacophony? Sounds good to me.

Decriminalised Futures is on view at the ICA, London, until 22 May 2022.