Explore the 2025 Power 100 list in full

What does the annual list actually mean? ArtReview reveals all…

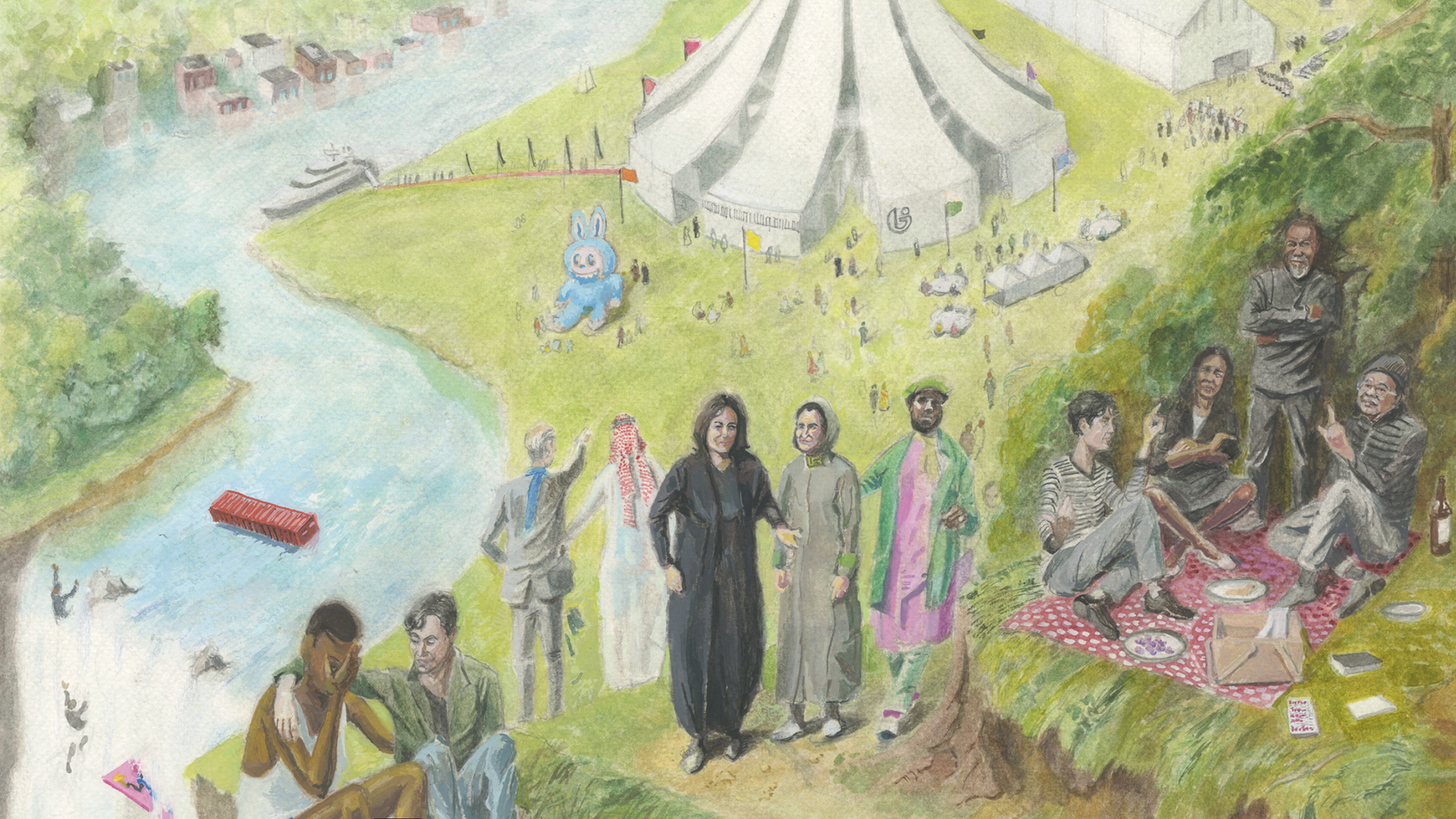

The Power 100 is ArtReview’s annual portrait of power in the artworld. It is an attempt to describe the individuals and groups that have shaped what art has been seen and how it has been seen over the past 12 months (broadly speaking, the calendar year). And yes, that is an indication that ArtReview views the artworld as, essentially, a social structure: a network of relationships that are triggered by the actions of individuals. Although within that you might also argue that different understandings of the network are what triggers the actions. But that could get complicated. And ArtReview’s list exists as a simplification. The point really is that ArtReview doesn’t regard the artworld as a purely economic system (which collectors bought the most expensive art, which galleries sold the most expensive art, which artists made the most expensive art, which museums showed the most expensive art), or an aesthetic one (which art ArtReview and its power panel like the most).

Alternatively, if the above seems too boring, you could look at ArtReview’s list for the gaps and absences it reveals. As a record of who (or what, given that most of those listed represent something more than themselves) is not on the list. As a description of what art has not been seen over the past 12 months. Although – spoiler alert – ArtReview can already tell you that the answer that will give you is ‘most of it’. But, crucially, this list is not designed to be how ArtReview and its cronies might wish the artworld to be; rather it’s an attempt to depict how it is. To find some sort of truth in a field in which subjective opinions, likes and dislikes often rule. And perhaps this is to concede that that’s (the confusing, obfuscating fog of opinions) the price to be paid when you constantly parrot the cliché that art is supposed to be a manifestation of a free space in which people (and sometimes more-than-people) can say whatever they like. All of which is, in a baroque sort of way, why ArtReview started making its list in the first place. It’s Sisyphean of course, because the artworld tends to conceal as much as it apparently reveals.

When it comes to the power players representing something more than themselves, you might read this list as an acknowledgement of the forces, some overt, some less so, that are shaping what art ends up in the public eye. You can quantify money and real estate, but how do you measure influence and inspiration? ArtReview’s way is to invite a panel of around 30 individuals, some of whom might well have been on the list themselves in another year, from across the globe and from all parts of the artworld to suggest the names of those people who have shaped the art that has emerged in their locality over the past year. They then argue, directly and indirectly (ArtReview is the middle-person here), about positions, email enthusiastic thumbs-up emojis, roll their eyes or write densely composed thousand-word analyses, or just sidle up to ArtReview at a poetry reading and whisper in its ear. These comments are collated, with new contributors brought in to test the ideas and prejudices of the rest of the coterie. The criteria for inclusion are: that each person of the Power 100 has had an active influence on the art being made and shown now; that influence has to be active (though thinkers such as Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Catherine Liu, Judith Butler and Fred Moten might not have published books in the last 12 months, their ideas have had tangible effect); and that their presence stretches beyond a local scene (while many act locally, the influence of that local action can reverberate internationally).

As with all lists, there are matters of convenience embedded within it (that’s the price of simplification). For example, on this power stage, all actors are typecast. Assigned roles: as artists, curators, gallerists, museum directors, funders, thinkers. Even though the reality is that many players do not fit conveniently into any single box. Starting with the individual who heads this list. Let’s borrow a line from physics and call this a way of overcoming complementary variables.

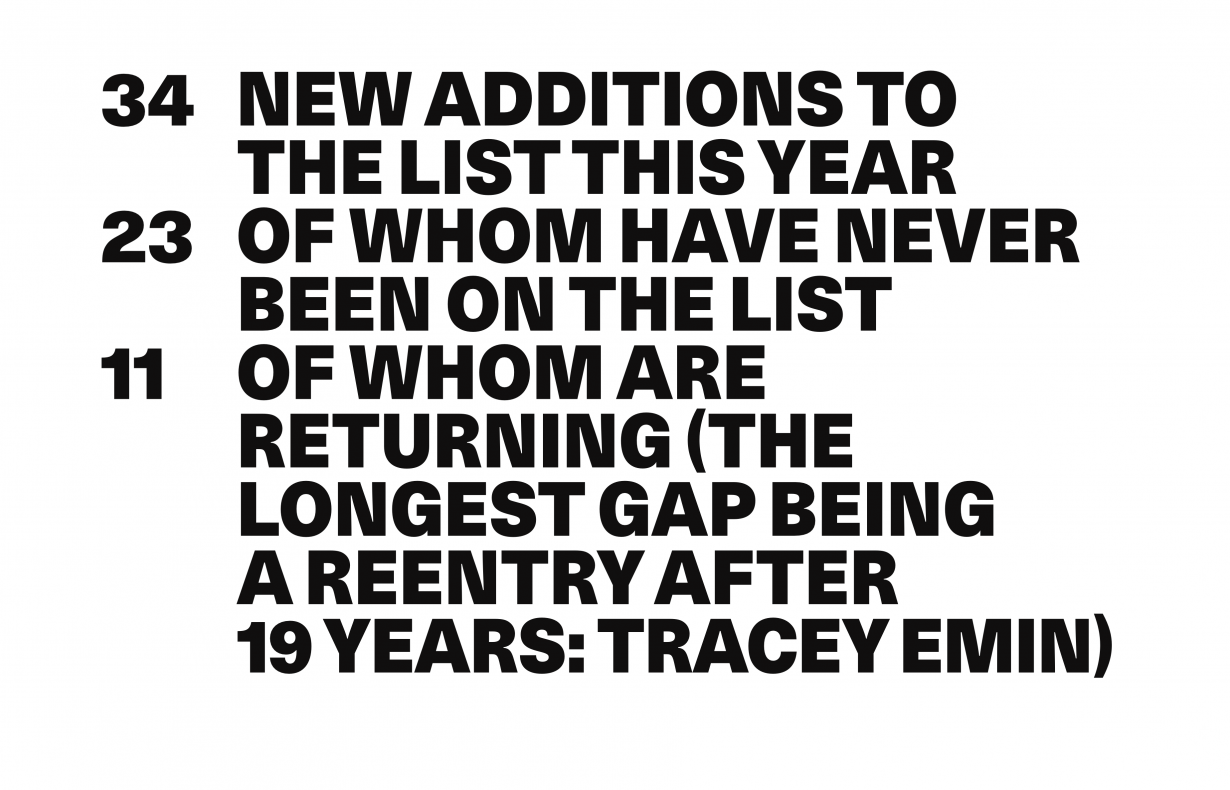

And talking of variables, there are only eight individuals or groups on this year’s list who were also on the inaugural Power 100 list from 2002, and of those eight, only one of those remains in the top 50 of the 2025 list (that’ll be curator Hans Ulrich Obrist). This might tell you that while the artworld is not prone to revolutions (despite its radical posturing), today’s global artworld is in some ways unrecognisable from what it used to be, back in the days when ‘globalisation’ was a relatively new idea. (In other ways, however, the artworld remains resolutely the same.) If our current moment is starting to realise that a globalised world is also a multipolar world, in which power is shifting away from the old centres, then this is a reality whose contours are visible in the artworld too. Of course, that the artworld is acknowledging this fact doesn’t mean that it hasn’t been happening, in the real world, for some time.

It’s tempting to say that Ibrahim Mahama’s placement at number one on this list is a reflection of a geographic shift. To invoke the late curator Koyo Kouoh, who died this year, but whose vision of the artworld will be enacted at next year’s Venice Biennale (and whose impact and influence can be tracked through this list), and to fete some sort of rise of the Global South through the list as a whole. This is what the artworld likes to do. The way it seeks to represent justice. While Mahama is the first person from the African continent to occupy the top spot, this is more the result of what he does than where he comes from. And, in general, the list favours actions over intentions. Beyond that, one might look to Mahama as emblematic of the way in which many artists today are taking control of the means of distribution (of artworks and of finance) as well as the means of production. Wael Shawky is ‘curating’ an art fair, Ho Tzu Nyen is curating a biennale. Perhaps it is a signal that the old ways of doing things – of the structures and systems and habits on which the artworld used to be based – are tired and broken, and that there are individuals doing their best to develop new ways of doing things out of the decline of the old.

Because like Mahama many of the other artists on this list, while still selling their work via galleries and appearing in museums and biennials – the old way of doing things – are creating their own infrastructures, which suggests a desire to bring artmaking closer to artworld-making. This could be by initiating residency programmes for other artists (Yinka Shonibare, Mark Bradford, Tracey Emin), or by building their own art centres and schools (Theaster Gates, Marina Abramović, Emily Jacir, RAQS Media Collective), or by creating new ecosystems though biennials and festivals (Bose Krishnamachari, Sammy Baloji). Many of these operate in locations and contexts outside of where commercial, governmental and philanthropic resources have traditionally been concentrated. Then there are groups like Forensic Architecture, blaxTARLINES and Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise who are reinventing how their work should be distributed and who their audience should be, and who consciously plug the economics (which is to say the wealth) of the artworld into quite different social contexts.

Much of this is altruistic, with redistributive and sometimes decolonial intent. But there is in this shift also a recognition that galleries – the mercantile types who have traditionally kept the whole show on the road by turning art into cash – are in a moment of flux: in many traditional art centres there is alarm about the closure of so many familiar mid-level galleries and many of the blue-chip megagallerists are reporting a dramatic fall in profits (of up to almost 90 percent in some regions according to newspaper reports). But that doesn’t mean that art no longer requires funding; far from it. And instead of embarking on more-or-less-public shopping sprees, the past 12 months have seen many art patrons, to some extent, cut out the former middlemen to instead provide funds directly to artists through their own private institutions (some with multiple venues), commissioning bodies or corporate sponsorship initiatives that go far beyond slapping a logo on a temporary show. Not that ArtReview is claiming that this is something new. Because, in many ways, it seems to belong to an older social order of private patronage spanning from the age of monarchy through the Renaissance through the colonial era and the Industrial Age, through to errr… the age of now. Still, all of the above has meant that most of the galleries that remain on ArtReview’s list (and there are certainly less of them than in the past) do more than simply sell stuff. Zwirner continues to operate a robust catalogue of artist books, zines and republished art historical essays; Perrotin’s been highlighting the porosity of the creative industries by inviting Pharrell Williams to curate a group show, while also playing host to a catwalk during Paris Fashion Week; and Hauser & Wirth, Goodman (not Marian, Americans) and Experimenter, for example, organise education programmes and (in the case of the latter) curatorial workshops, looking to create and represent ecosystems broader than themselves.

If you’re looking for something really new, however (and ArtReview’s PR people keep telling it that you are), one might look to the increasing presence of the Gulf States near the top of this list as they continue to pour enormous resources into arts and culture, both as a means of shifting the emphasis of their otherwise oil-centric economies, as well as recognising the arts as a means of burnishing a national brand. With culture wars and austerity raging in old art-power centres such as the US (where Donald Trump’s executive orders are interfering with the programmes of supposedly independent, federally funded museums), Germany (where cultural-political dictates criminalising how the Israel-Gaza conflict can be spoken about have led to a free-speech crisis in its once thriving arts scene) and the UK (broke and floundering), the Arab world is increasingly becoming a platform in which artists and curators can broaden and expand their practice. If this is a reflection of the more general belief that art has some sort of (soft) power, then you could see it too in the work of curators such as Diana Campbell, whose Bukhara Biennial shone a light on a place that most art lovers couldn’t really place on a map, other than as somewhere they might once have flown over.

On this year’s list are actors with coexisting approaches to what art can be, and what it can do now, and for whom. Some of these are in direct competition, others operate in entirely separate spheres. Recent years have highlighted some of art’s inabilities to face up to the harsh realities of a changing world order. If this list maps the passing of a once Western-dominated artworld, what and how should emergent local scenes share or exchange internationally? Will the decline of once dominant centres simply be replaced with domination by new ones? When seemingly fundamental pillars of art’s familiar hierarchies – museums, galleries and the art market – are beginning to wane, are they simply being replaced by alternate versions of the same old model?

Explore the 2025 Power 100 list in full