From Carol Rhodes’s cool aerial views to the voyeuristic animal fantasy of Amanda Moström, our editors select shows to see during London Gallery Weekend

Harley Weir: The Garden

Hannah Barry, through 13 September

Harley Weir got her start as a teenager after posting photographs on online photo sharing platform Flickr. Her images of friends and family were taken on cheap analogue cameras and often featured accidental light leaks and colour bleeds. It was here that she was spotted by creative directors from the fashion industry, keen to capitalise on her youthful perspective and arresting engagement with the materiality of her medium. Yet alongside her high-profile editorial work of the last two decades, she has maintained an intimate artistic practice that upholds and expands the formal experimentation of her early days. Weir takes the exhibition’s title as a site of fantasy, in which she reckons with the life cycle of flowers, plants and trees as a metaphor for the ageing human body. In one photograph (Function, 2017) a baby sucks at their mother’s breast, shot under artificial lights at such close range that each goosebump upon the stretched skin is plain to see, while in another a nude figure lies stretched beneath a taut and translucent sheet (Birth, 2024), disturbingly suggestive of both extreme beauty treatment and a shroud. In ongoing project Sickos, she fuses bodily fluids and supplements – blood, sperm, vitamins, contraceptive drugs, egg freezing hormones – with photo developing chemicals to chemically alter the make-up of the resulting images. Weir demonstrates how both the body and the camera can be manipulated and transformed, cosmetically enhanced and broken down to their core elements. Louise Benson

Amanda Moström: Douglas

Rose Easton, through 28 June

A set of staged portals and peepholes greet you in the gallery, four doorway-shaped sculptures hanging from the ceiling. The yellow beads of Set about it like a girl inspired (all works 2025) create a large keyhole shape, casting the show as an elicit peek into some locked room. Though what we see inside is more like a surreal dreamscape, with a streak of long black horse hair trailing from the front of a metal floor fan (this is the eponymous Douglas), while the fragmented image of an oversized, fluffy yellow chicken is printed across the dozens of CDs dangling from Enough muscle. Three stools of varying sizes are propped in a corner: one enables you to peep through the eyeholes carved through the wooden slat of Pouty lips and dark doe eyes; another to fit into the hanging arch of sandy-coloured horse hair of Pouting, as if an exaggerated wig. Go try it on, take part in Moström’s playfully subdued and voyeuristic animal fantasy, as she nudges you to be the animal you’ve always dreamed of being. Chris Fite-Wassilak

Polyphonies

Ames Yavuz, through 26 June

If you know London’s art scene, you’ll know that summer only means one thing: group shows. If you must see one, then make it Polyphonies. Ames Yavuz opened its new London space in May, and its sophomore exhibition sets out to ‘challenge the intrinsic hierarchies and biases of language’. Yet, as the title suggests, this will inevitably encompass sound, frequency, concepts of recording and receiving. First Nations artist Betty Muffler’s ngangkari (or healing) paintings work against the generational trauma of an her ancestry, the Pitjantjatjara Yankunyjatjara people, whose land was the site of atomic testing by the British forces in the 1950s and 60s. Comprehension and healing can go hand in hand. Then there’s Thania Petersen’s pictorial embroideries, largescale storybooks traversing empire and postcolonial distortions. (Her 2022 installation Rampies Sny, a wall of perfumed organza satchels filled with botanical cuttings, inspired by a Cape Muslim tradition, was a highlight of Zeitz MoCAA’s Indigo Waves and Other Stories.) And there’s Ana Bidart’s Calendar (2025), a durational work which stamps an open canvas booklet with a wedge of pigment, connected by a piece of string to the gallery’s front door. Every time someone enters and exits, an inky stamp is marked with an ironic thud. Alexander Leissle

Kayode Ojo: An angel is just a messenger

Maureen Paley, through 8 June

It’s not every day that you see an item’s full description from amazon.com listed in the materials of an artwork. Yet Tennessee-born Kayode Ojo’s sculptural configurations of readymades are built upon precisely that unglamorous history – both digital and physical, commercial and personal. Clothing (typically bought from fast fashion online retailers) is hung by the artist from IKEA-made knock-offs of mid-century furniture and music stands, or else draped with novelty jewellery, toy handcuffs or bootleg handbags. In the accompanying inventory for Absinthe Robette (Bree) (2023) – an absurdist figure fashioned from a slip dress and delicate music stand – a set of glasses is given the description ‘Cheers Champagne flutes for Wedding Party Anniversary Christmas Vintage Pattern Embossed Premium Glass’. Rather than conceal their origins, Ojo adopts the floridly commercial language of the online marketplace to place front and centre their journey from the internet to the gallery. Oh, and to the club too. He frequently gravitates towards the crystal and rhinestone-encrusted shimmer of wearable items seemingly designed to exist solely under the artificial lighting and mirror ball of the nightclub, echoed in his photographic archive of images taken at close quarters at parties and on nights out. He is interested in the tension between fantasy and reality, and between the real and the artificial, as captured through the design and circulation of objects. Louise Benson

Carol Rhodes: Sites

Alison Jacques, through 9 August

Imagine you are flying. As a genre, landscape painting always takes a point of view, that of the individual painter located in the physical world, looking upon a vista that is more natural than it is urban. Feet on the ground, the painter tends to look out and up – to mountains, rivers, woods, hilltop villages, whatever. The Scottish artist, who died in 2018, quite literally took a different angle. From the mid 1990s, she painted views of the land as if seen from a great height. Pale, shadowless expanses of field and forest, lake, cliff and shoreline, bisected by and overlaid with the various forms of human habitation and industry; roads and roundabouts, motorways and intersections, factories, housing estates, airports, car parks. This cool, taxonomic view is annotated in canvases made up of spare, slow brushwork, which toy ironically with abstraction, even as they draw us to consider the landscape unsentimentally and in the third-person, to see human society as a set of systems and machineries, exchanges and flows, of people, places and materials. Piles of aggregates waiting to be shipped, the slag heaps of mining and the scars and gouges of open quarries are equally part of Rhodes’s attention, suggesting an ecological subtext. But however you might interpret Rhodes’s impassive, seemingly objective eye, it’s impossible to ignore her care for design and the pleasure of composition – in the way the curves of roads, the contours of topography and the punctuations of buildings come together as balanced, architectonic ensembles, rendered in the painter’s palette of pale pastels, earthy tertiaries and tarmac greys. Maybe rooted in her earlier years spent in feminist and left-wing activism, there’s a utopian edge to Rhodes’s art: her paintings and drawings seem to make an analogy between the composition of painting and that of society, as if human civilisation might itself be a work of art. J.J. Charlesworth

Gala Porras-Kim: The Categorical Bind

Sprüth Magers London, 4 June–26 July

Last time I spoke with Gala Porras-Kim she was busy trying to contact the dead. Her precise communication method was ‘encromancy’, an early form of ink divination, and she was trying to reach the first-century BCE citizens of Shinchang-dong, an area of present-day Gwangju (or at least their spirits), to ask if they were happy in the knowledge that their material remains were on show in the city’s National Museum. This is the Colombian-born, US-based artist’s modus operandi, a kind of institutional critique, specifically dealing with issues of museum ethics, operations, ownership and restitution, in a practice that is never dry or hectoring. It has won her fans, especially in the museum world, precisely because she is dealing with many of the thorny issues that museum workers are themselves thinking about. For her current solo exhibition at Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome (though 1 October), she interviewed the institution’s curators as they handled the object they felt closest to; the resulting videoworks leaves only the hands (with the objects and the rest of the interviewee’s bodies removed) to create portraits of care and intimacy. In another current solo show, this time at Carnegie Museum of Art (though 27 July), she turned her attention to the museum inventory, questioning how objects are labelled and categorised, how some are regarded as art and others ‘artefacts’. For her first solo show at Sprüth Magers, expect similar challenges to epistemological conventions. Oliver Basciano

Arthur Jafa/Mark Leckey: Hardcore/Love

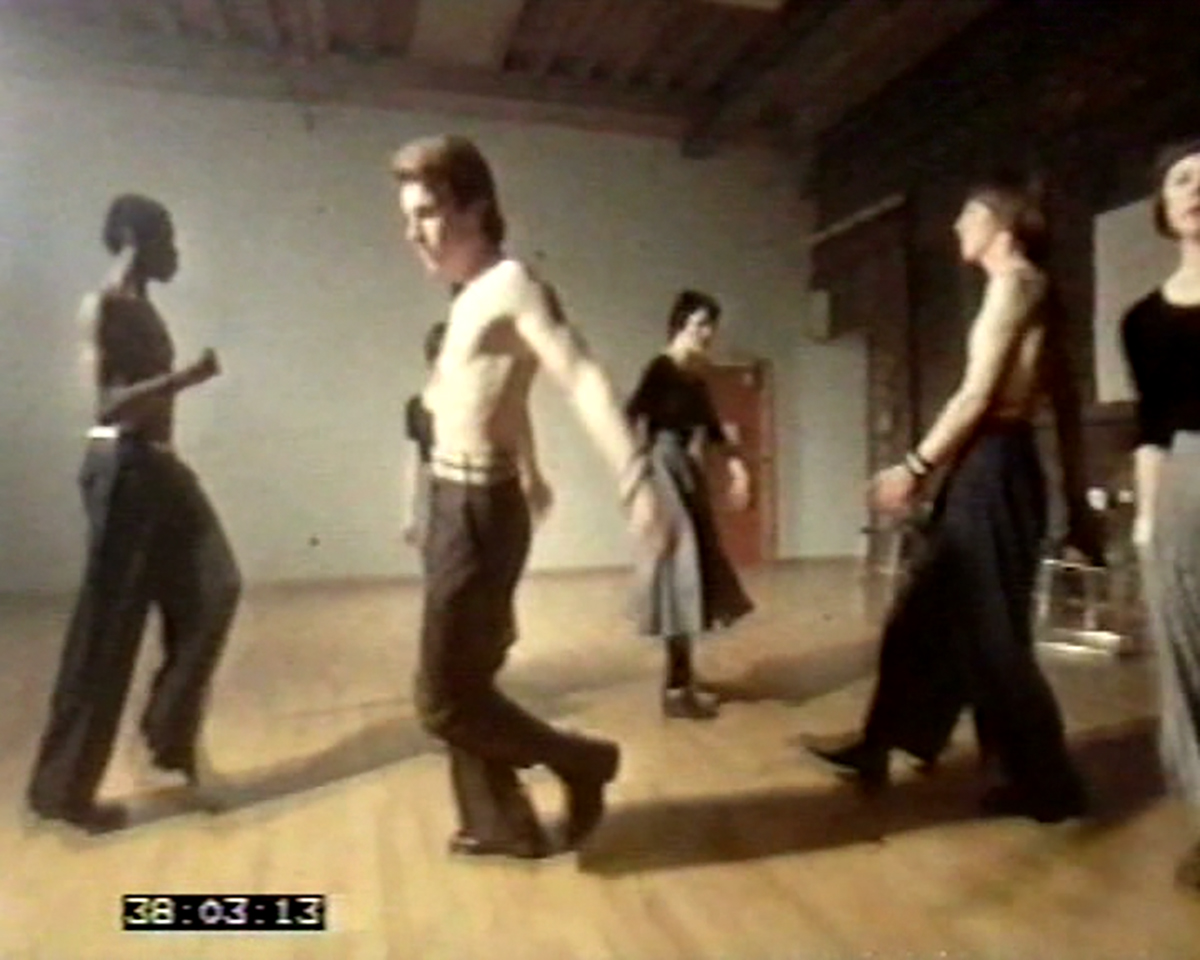

Conditions, Whitgift Centre, Croydon, 28 June–10 August

Mark Leckey once claimed that the most exciting art form was the music video. In the age of infinite scrolling, Leckey’s perspective on the creative potential of new media has proven prescient. In 2025, it is telling that his 1999 film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, with its spliced video footage of nightclub revellers and amalgamated sound, feels strikingly contemporary. In typical Leckey fashion, the work pairs joy with a pervasive sense of melancholy – what the artist has called ‘sweet-sadness’ – and a heightened awareness of the inevitable march of time. It is that same sweet-sadness that runs through Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016), a fast-moving progression through a succession of images and short clips from a swelling, hugely varied range of sources – from silent films to phone footage of police violence to the artist’s own home movies. A reflection on the African-American experience, Jafa expands the music video format (the work is accompanied by Kanye West’s ‘Ultralight Beam’, 2016) to reflect the often-fragmented experience of the digital age, when humour and crisis can exist side-by-side. That the two works will be screened together for the first time this month at Conditions, an artist-run project space and studios located in a shopping centre in Croydon, points too to the mutability of the music video, moving easily between the television, the phone, the gallery and, yes, even the mall. The exhibition is the idea of art dealer Gavin Brown, a longtime friend of Leckey’s (it was to Brown that Leckey proclaimed the artistic potential of the music video; Brown responded by asking him to prove it, and Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore is the result, or so the story goes). Louise Benson