David Hammons’s monument to Gordon Matta-Clark raises uncomfortable questions about how we define ‘public’

When the piers along the west side of Manhattan came tumbling into the Hudson River in the 1980s, their destruction signalled the beginning of New York’s redevelopment as a capitalist playground. For several decades, as industry fled the city, the sheds had been a different kind of playground, one where men cruised for sex, and the order to demolish them was followed by other measures to criminalise gay spaces at the height of the AIDS epidemic. Lost with them were the many renegade artworks completed in their warrens of mouldering timber and rusted steel, most famously Gordon Matta-Clark’s Day’s End (1975): a series of cuttings from Pier 52, including a monumental lens through which light would flow at sunrise and sunset.

Matta-Clark died in 1978, at the age of thirty-five, and Pier 52 came down a year later, making Day’s End the stuff of legend. That legend now lives on in New York’s largest public artwork, also called Day’s End, by David Hammons, who has traced the outline of Pier 52 in steel over open water. The steel beams, made from the same grade used in nuclear power plants, slot together so they won’t buckle or bend. Although designed to be permanent, the sculpture looks temporary, like the armature for a tent. Light doesn’t pass through it so much as swallow it whole: the work has been buffed so that it gleams in the afternoon sun like the glass condominiums that now line the West Side Highway. In this sense the new Day’s End is an apt symbol for the new New York: shiny and unbending.

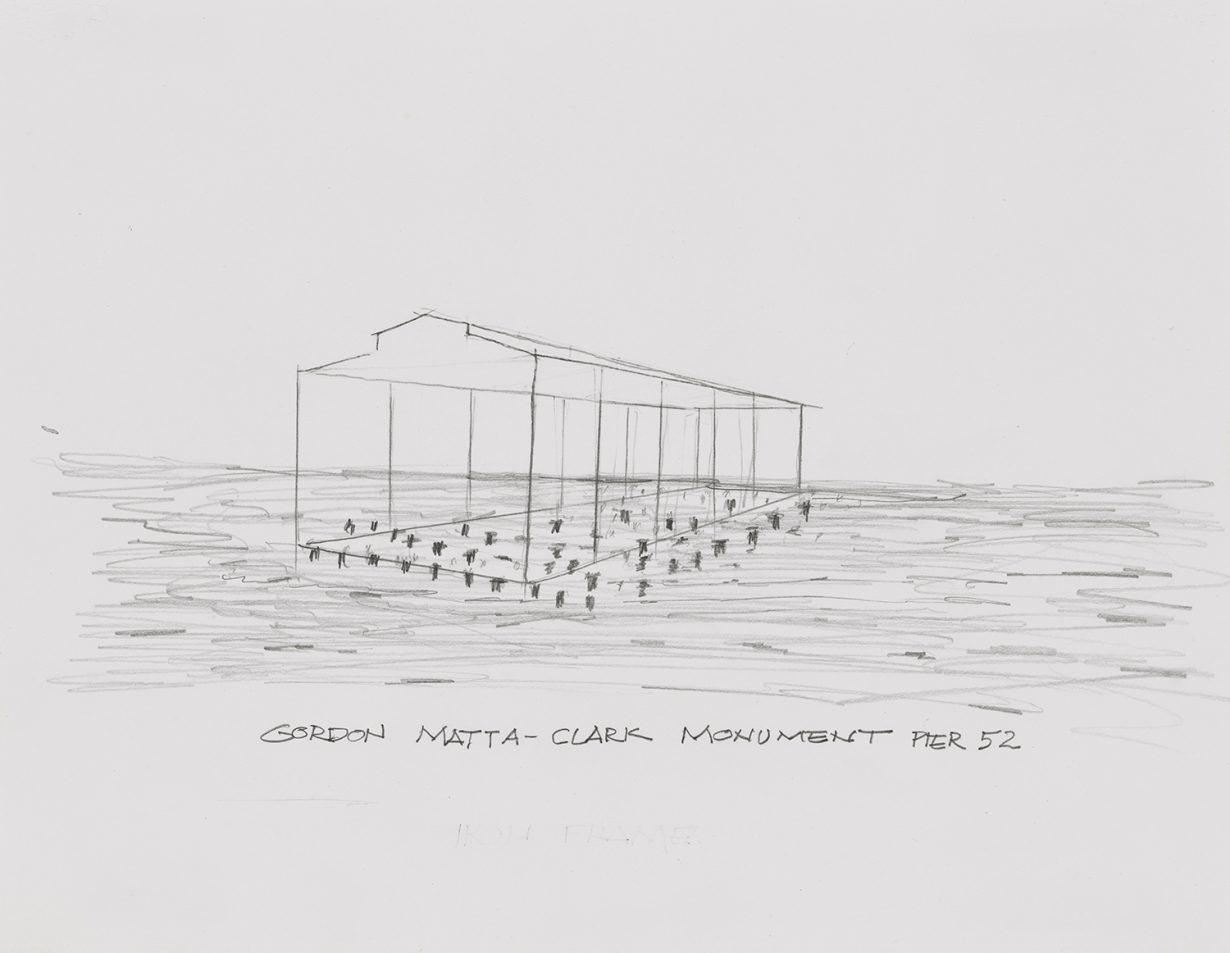

Hammons’s Day’s End is itself a legend in the making. According to Adam Weinberg, Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, during a 2015 meeting with Hammons in the museum’s recently completed building along the Hudson, the artist kept staring out of the window towards the broken pylons of Pier 52. Weinberg noted that the site was where Matta-Clark completed Day’s End. Two weeks later, a sketch arrived from Hammons with the epitaph ‘Monument to Gordon Matta-Clark’. Weinberg threw the full weight of his institution behind its construction with relatively little guidance from Hammons, who noted only that the structure should be as minimal as possible and follow the pier’s original contours.

Few people remember having seen Matta-Clark’s Day’s End, though photographs by the gay African-American artist Alvin Baltrop, who spent decades documenting life at the piers, show lithe young men sunbathing nude beside it. Pier Groups, a 1978 gay porn film, used the work as a backdrop; in Jonathan Weinberg’s eponymous 2020 book, director Arch Brown told the author that he had no idea the cuttings were an artwork. The existing inhabitants of Pier 52 were generally more interested in other things. Matta-Clark, meanwhile, disdained them, locking the building for months while he worked and complaining about ‘menacing characters’ and a ‘sadomasochistic fringe’. Baltrop’s pictures show that, while S&M was indeed part of the sexual culture along the waterfront, most of the queers were just there to find shelter or relax together. (This was certainly more difficult once Matta-Clark had cut the pier in half and flooded it with light.) The plaque adjoining Hammons’s sculpture makes no note of Baltrop or of cruising. Instead, it contributes to the hagiography of a homophobe.

In a 1976 interview with Donald Wall, Matta-Clark described Pier 52 as ‘a special stage in perpetual metamorphosis’, adding that he did ‘not want to create a totally new supportive field of vision, of cognition’ but rather ‘reuse the old one, the existing framework of thought and sight.’ He called this ‘anarchitecture’, imagining renegade adaptations of decaying urban infrastructure as a source of liberation and a response to the threat of climate change. The new Day’s End, however, is a product of immense physical and bureaucratic resources, a framework that is perfect and unchanging. This is less reflective of a flaw in Hammons’s design than of how impossible it is to incise a landscape so thoroughly policed and privatised. The neutered pylons that inspired his sketch were removed to make way for his work; witnesses to the city’s violent transformation, their presence was far more haunting.

Hammons has said little about the public monument, which is full of literal and metaphorical gaps. We can take him only at his word: a title invoking just one history to a contested site. Day’s End thus raises uncomfortable questions about how we define ‘public’. Matta-Clark didn’t consider queers his public; the Health Department didn’t consider his artistic milieu one, either. The joggers and cyclists who pass the new Day’s End may not notice its lack of didacticism. Depending on the angle of the sun, they may not notice the sculpture at all. This could be by design. Instead of history, Hammons’s public may be looking for a mirror.