The exhibition is at its best when artworks appear to disrupt the event’s sweeping therapeutic narrative

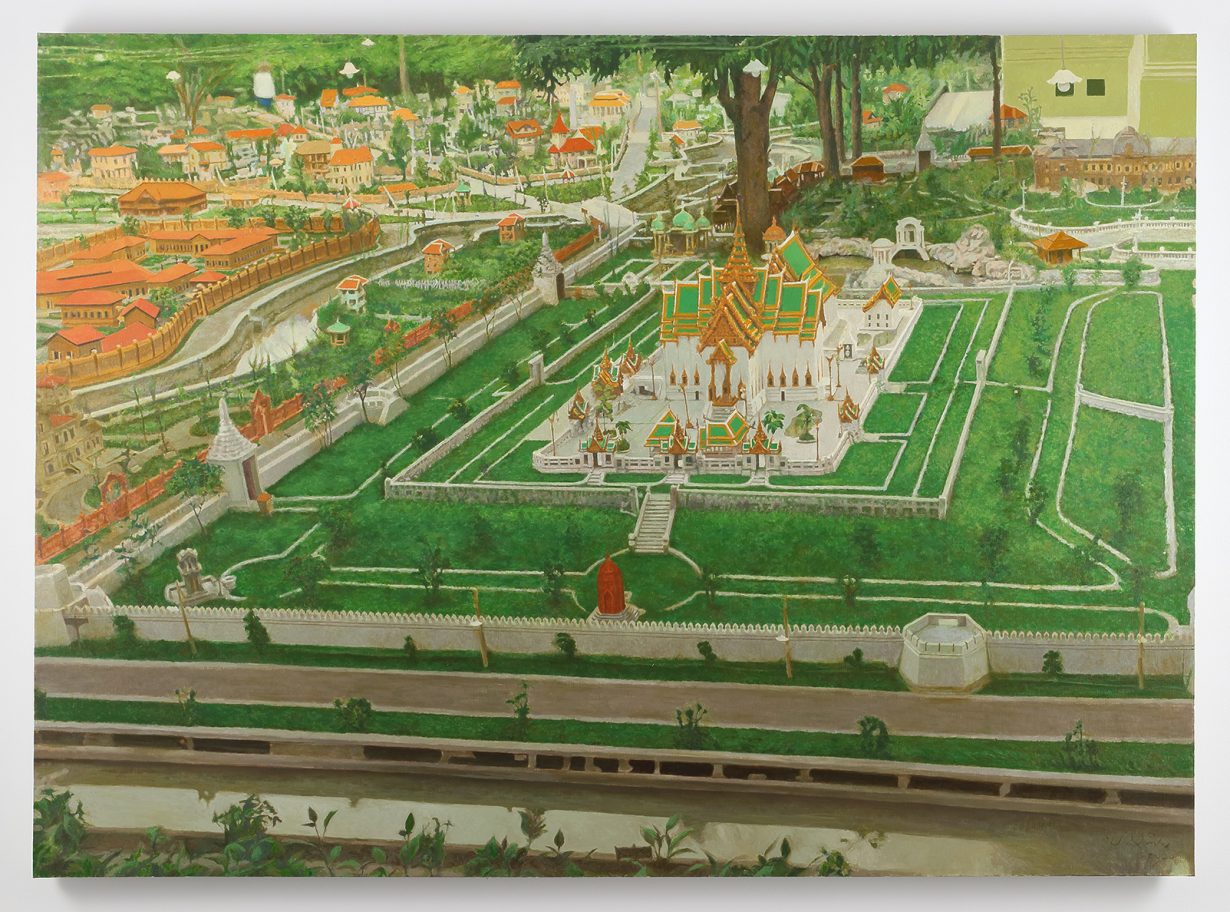

The Thai Kingdom is, for once, a picture of civic health. Tucked away in one of the second Bangkok Art Biennale’s ten venues, Prateep Suthathongthai’s photorealistic painting Dusit Thani Province 1 (2020) depicts a pointy-roofed Thai temple hemmed in by neat lawns and white crenellated walls. Just beyond lie the pintsize, European-style buildings that made up King Rama VI’s Dusit Thani, a miniature model city that served as his proof-of-concept playground for the principles of democracy, complete with party elections, a constitution and even a daily newspaper, back in the 1910s. Suthathongthai’s carefully hand-rendered recreations of archive photos are joined by large-format UV prints of the project’s original blueprints, while projected on the floor is drone footage of a dusty northeastern Thai village built by the government for former Communist Party members – failed fighters for a very different utopia – during the 1970s.

The work hangs in The Prelude, a marble-hewn show-suite for One Bangkok: a 167,000 sqm, ‘game-changing district’ being built, just steps away, by a sister company of BAB 2020’s key sponsor, Thai-Chinese drinks conglomerate ThaiBev. Upon completion, this US$3.9-billion development will be ‘a new global landmark on the world stage’, replete with ultraluxury condos, office towers, retail precincts and culture spaces, not to mention prices likely to keep nearby slum dwellers at arm’s length. Emerging from The Prelude, I am met by the clanging of its breakneck construction, and struck by the poles of inertia, subjugation and progress that Suthathongthai brings into question: true democracy still remains a Thai fantasy of sorts, yet profoundly inequitable urban gentrification schemes sprout as if by magic.

After the inaugural edition in 2018, several academics concluded – in contrast with a heap of positive media coverage – that BAB’s artists had been co-opted by an ungainly spectacle. This mega-event aimed at belatedly branding Bangkok as a city of art affirmed both the neoliberal agenda of its backers and the charismatic careerism of the esteemed curator helming it, all while saying next to nothing about the political woes afflicting the country and seeming wildly out of step with the unruly, anti-institutional urges of many emerging Thai artists and events. For the most, I agreed with these counterhegemonic critiques – but Suthathongthai reminds me that things aren’t so cut and dry. Bringing the iniquitous character of the country to the fore, subverting the dominant hegemony, his work shows that critical artistic practices can, to paraphrase political theorist Chantal Mouffe, ‘disrupt the smooth image that corporate capitalism is trying to spread’.

Scaled back but only slightly humbled, BAB 2020 is at its best at moments like these: when the platitudinous ‘hope’ and ‘survival’ rhetoric of artistic director and BAB mastermind Apinan Poshyananda’s ‘Escape Routes’ theme – spurred initially by the knottiness of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals but since amplified by the pandemic – finds little sanctuary; when works seem to misbehave by offering up something richer and more rooted than the event’s sweeping therapeutic narrative and hubristic attempts to remake the world would seem to allow.

At the city’s ailing kunsthalle, for example, Thai auteur Pen-Ek Ratanaruang’s short film Two Little Soldiers (2020) follows two squaddies as they fish and talk by a forest-fringed pond in a Thai army camp. In this sketch, lifted from a forthcoming feature inspired by Guy de Maupassant’s short story ‘Deux Amis’ (1882), a crackling radio reports news of violence on the streets of a remote Bangkok as they idle, leading us to ponder the extent of their complicity. Another video, at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC), the BAB’s main venue, I-na Phuyuthanon’s Harmonimilitary (2020) explores strife in Thailand’s deep south simply yet affectingly: dressed in a flowing turquoise burka, she ambles around a lush village where separatist violence has been met with public vilification and peacekeeping operations. On an upper floor at The Parq – a sparkling new office building also linked to ThaiBev – a painting by Yuree Kensaku, Bleu Blanc Rouge (2020), raises the spectre of republicanism with a cartoonish send-up of Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830), complete with a Tricolore-waving chicken. And nearby, relative newcomer Rungruang Sittirerk’s The Metamorphosis (2020) is an installation of 1,997 clay works – a reference to the year of the Tom Yum Kung financial crash – located beside a window overlooking the Klong Toey slum, source of much of the city’s cheap labour.

If this selection implies a certain bias towards the local contingent, it merely reflects facts on the ground. BAB 2020 has dual missions: introducing 31 Thai artists to a globalised international contemporary artworld on one hand; bringing works by 55 of that world’s artists to Bangkok for its citizenry’s betterment on the other. It excels at neither but proves far more accomplished at the former: while most Thais contribute new commissions, most of the international contingent – Ai Weiwei, Yoko Ono and John Akomfrah among them – deliver old works that serve to dilute rather than reinforce. Many, especially the glut of photography, seem entirely decoupled from their counterparts, immediate context, even their place in time. Why are they here? Most appear to have been selected simply because they were at hand, or easily executable mid-pandemic, or help summon the star power to which Poshyananda is clearly so in thrall.

He is BAB 2020’s biggest enigma. In the runup, he revealed that the decision to go ahead largely rested on a calculated desire to capture some of the attention that would have been directed at the better-established, cancelled competition (this was later confirmed in a press kit underscoring the ‘big opportunities to gain much more share of voice in international media’.) In the opening days that raw opportunism was replaced by a careful defensiveness, as he fielded questions about the government’s heavy-handed suppression of the recent student protest-movement, and the 25 BAB artists who had issued a letter railing against it. (An official written statement in support of the protesters never materialised, but Poshyananda tried to burnish the BAB’s reputation – ThaiBev’s symbiotic ties to the palace, government and military be damned! – by claiming solidarity.) Ever since then, the impression of a one-man show, an auteurist affair, ‘smooth image’ personified, has been hard to shake. In every talk, video tour and media interview, he appears every inch the smart-casual showman: repeats his ‘Escape Routes’ lines and opines on the logistical challenges overcome. Littered with references to power-mongers, pollution, greed and plagues, his BAB 2020 writings, meanwhile, continue a long Poshyananda tradition of emphasising art’s conciliatory and cathartic role, only to retool that schtick for the geopolitical and epidemiological shitshow that is now.

All this posturing aside, there are rewarding moments. A strong vein of ecologically minded work runs throughout – fitting at a time when Bangkok’s PM2.5 levels are slowly killing us. There is also a peppy section at the BACC where fantastical visions from across the Middle East and Asia collide. This includes, among other works, Kubra Khademi’s gouache drawings of eviscerated female bodies (The Birth Giving, 2019); the chimera-filled Mongol Zurag-style paintings of Nomin Bold and Baatarzorig Batjargal; and Chantana Tiprachart’s beguiling tone poem in Lai Torn (2020), a video in which a boat decked with candles for the Lao-Thai Naga festival slowly burns. And winning the prize for biggest showboat is Anish Kapoor’s Push/Pull (2009). Hearing someone compare this round monolith of soft, cinnamon-red wax to a giant Babybel quelled only some of its ferocity; it springs, like a blood-curdled sledge sent screaming from one of the 16 levels of Buddhist hell, out of the marble floors of the famous Wat Pho temple’s sermon hall. Speaking of hell, his assistants apparently endured two weeks of hotel quarantine, as did performance artists such as Melati Suryodarmo and Miles Greenberg, so the show could shuffle on. You have to admire such dedication.

Still, such pulses of pleasure are always tempered by a nagging sense that audience and artists alike would be better served by an event that smacks less of spectacle-led short-termism. In a press conference last October, BAB was blithely repositioned as a national saviour, as a ‘prototype event’ that will help recalibrate and revive the country’s decimated tourism industry (it failed dismally, through no fault of its own). But, from my vantage point, its own long-term fate looks even more questionable: it has revealed no collecting urge, no nurturing instinct, no memory beyond its duration, no clear sense of mission and no roadmap beyond its next edition. This lack of focus is doubly alarming when you consider the core sponsor’s fixation on the numbers (allegedly, 3 million Thais and foreigners visited, and over 4.5 billion baht was stimulated, in 2018) – and the fact that those numbers have now, surely, all but collapsed.

The net result is all-too familiar: a biennale no greater than the sum of its parts, an expolike gathering that talks a good game but, in actuality, offers up only random ‘discoveries’ – a bit of art from here, there and just about everywhere – as its intellectual prize. As for the near future, the escape route to better global art pastures that Poshyananda has built for Thailand could well vanish as soon as 2023: the year his and ThaiBev’s commitment ends and, conveniently, its dream city launches.

Bangkok Art Biennale: Escape Routes, various venues, Bangkok, until 30 April