The Swiss artist invites us into his living room as he makes his latest tribute to Simone Weil

By Mark Rappolt

It’s 2 April 2020 and Thomas Hirschhorn is at home. So are we. For a moment – for ten minutes and 55 seconds – his apartment is ours. We don’t know this immediately, however. At the beginning we’re looking out of his window down onto a Paris street corner. It’s sunny, but no one’s about. We see what he sees. We’re inside, looking out. Not outside looking in. The psychology is genius. It’s as if a Vulcan mind-meld has happened. He probably doesn’t have time for Star Trek, though. And before we have time to wonder if we’re being manipulated, Thomas has manipulated his phone.

We hear his hands fumbling around its case. A flash of something pinned to the wall, a skid past some bookcases. And then we see him. He’s got his phone raised above his head so that he looks up into the camera. Just enough to make it appear that all this is as uncomfortable for him as watching his video is easy for us. And to further promote the notion that the viewers are in control. As if.

“We have to stay at home,” he says in a tone (his usual one) that is so dry it’s hard to work out if that was a statement of fact or a command. He tells us that while he has been at home, he has been at work. Not lolling about watching other people’s lives on video. (That last bit is implied, but not said btw.) More precisely, he’s been making a ‘Simone Weil map’ in honour of the French philosopher, mystic and activist. We can see a part of it from our elevated position. Over his shoulder. In the middle of the room. Occasionally he pronounces her name in the German fashion, where that first ‘e’ is not silent.

The map’s big. Occupying most of the floor. His life is full. So full he barely has any room for trivialities such as living space. And so, presumably, was Simone’s. Seeing as it’s her life that’s actually cluttering up his floor. Why are we here? Don’t we have things to do? We’re here so that Thomas can explain his working process, he tells us. Thank God.

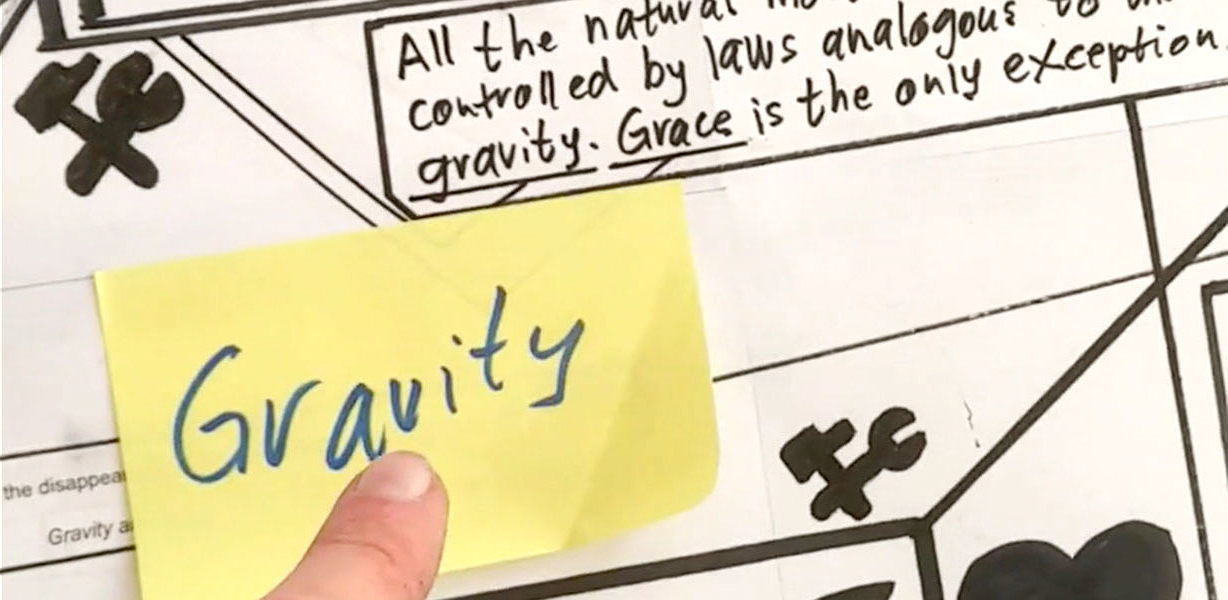

The map’s so big he has to walk on it so that he can show it to us. Barefoot. We’re touching the artwork, using the artwork. Partially naked. It’s intimate. It’s great. We’re back to the Hirschhorn-eye view. Occasionally a toe pokes into shot. We pass a litter of books, Post-its, marker pens, sticky tape – tools. And tools are evidence of work. Fresh work. We don’t have time for shallow thoughts, like where he got his sofa from. I was admiring a particularly nice Habitat shelving unit over the shoulder of Peter Saville last week, while he was part of a Zoom conversation about working with the British band New Order. It was particularly nice because I have the same model. So I became curious as to what other products the graphic designer had assembled to match. And whether or not I had any of those too…

“I do a map because it permits me to understand, to learn more about the work of Simone Weil,” Thomas barks. I don’t know much about her work. I’m opening another window to go on Google. And another one to update my Amazon wish list. On which the Weil books now sit, just above something that may or may not be Peter’s lamp. The words ‘WORKER’, ‘GRAVITY AND GRACE’ and ‘THINKER’ flash past on the map. In the shouty block capitals I’ve reproduced and that are a signature of Thomas’s work. The map is structured of linked boxes containing text and image that suggest, when the drawn links are many, a structure of diamonds and prisms. The point is this: like much of Hirschhorn’s work in the collage/mapping vein, it looks like science; it smells of facts.

“Everything on this map is important,” he says, as if on cue. He can read minds too. “Everything counts. Everything that needs to be on this map is on this map. Nothing is not important.” As GRAVITY AND GRACE comes into view, he shows us the book itself. In the original French. La Pesanteur et la Grâce. He doesn’t really say why the languages are changed. Perhaps it’s because he’s Swiss. Or because the gallery that’s hosting this video (Gladstone) is based in the US. Perhaps he’s just showing off. But there’s no time for worrying about any of that. He’s found some powerful sentences. He wants to share them with us.

I close the other windows. And won’t open the next until the video ends and we’re back where we started, staring out of his. By then he will have convinced me that Weil is really important, as is plotting your thoughts in relation to those of others. And then I’ll really be ready to map out my bookshelves, my library and the rest of my life. Screw Peter’s lamp.