ArtReview sent a questionnaire to artists and curators exhibiting in and curating the various national pavilions of the 2024 Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published daily in the leadup to and during the Venice Biennale, which runs from 20 April – 24 November.

Yuko Mohri is representing Japan; the Pavilion is in the Giardini.

ArtReview What do you think of when you think of Venice?

Yuko Mohri A bit of a cliché, but I guess it’s “the city on Water” (lol). I have already spent two weeks in Venice in summer 2023 to study the exhibition site, then again this year about a month and a half between late January and February to produce the work. I was surprised to see the traces of the flood damage that occurred in 2019 still visible on buildings throughout the city. Water continues to fascinate us, but we are also at its mercy.

AR What can you tell us about your exhibition plans for Venice?

YM I will be showing two works on the theme of water. Sook-kyung Lee, the Korean curator whom I asked to be in charge of this year’s Japan Pavilion, was the artistic director of the Gwangju Biennale in 2023, in which I participated. The theme she set for this edition was ‘soft and weak like water’, a quote from Laozi. Although neither Korean nor Japanese, Laozi was a Chinese thinker active in the sixth century BC, whose unique ideas are widely known in Asia to this day. The rich tradition of East Asian classic literature reminds us that culture can fuel the political tensions between national identities (Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, Japanese, etc.), but it can also serve as a medium to bridge borders and continue conversations across generations. An artist as much as a philosopher, Laozi of course embodied the latter function. We need to have water on our side. It was the ocean that has separated and connected nations.

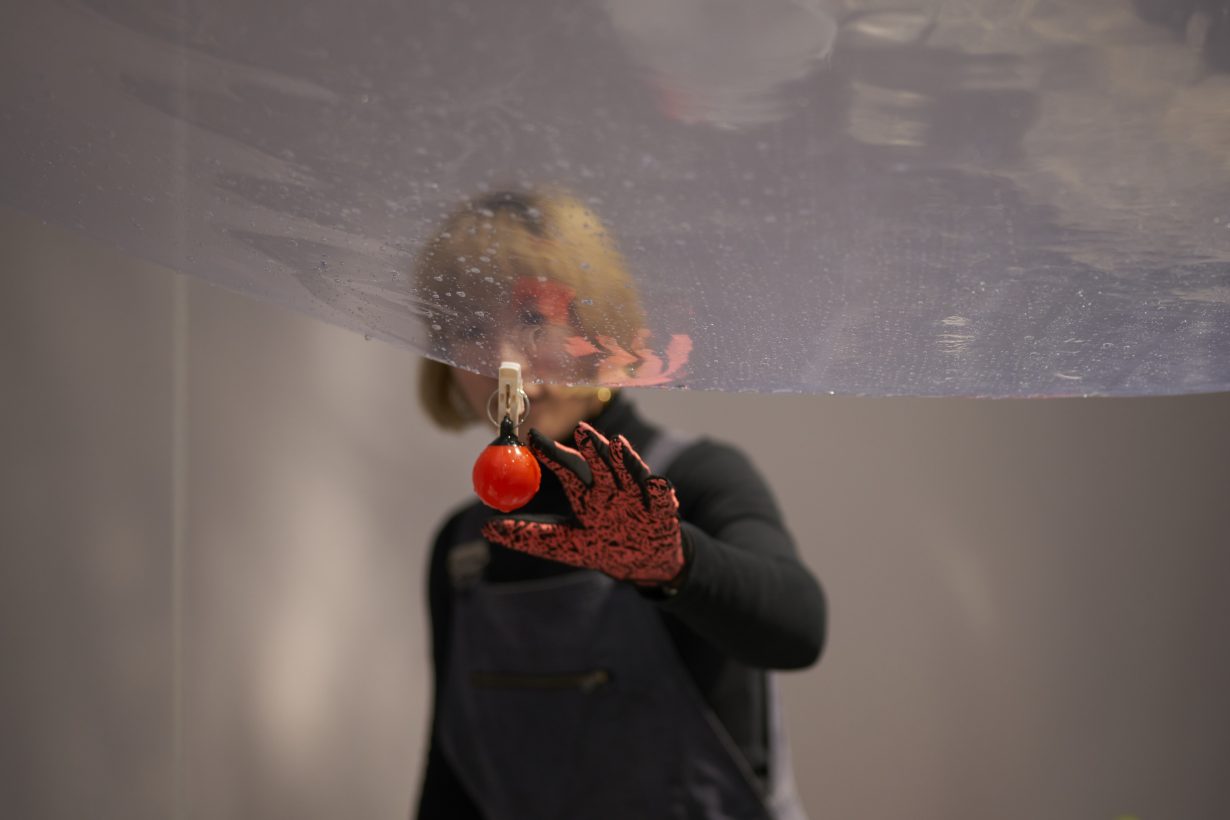

What is unique about my participation in the Venice Biennale this time is that I did not produce the works in the studio and brought them to the site, but sourced all the materials except for the equipment from local general stores, antique markets, grocery stores, and supermarkets. I turned the Japan Pavilion, the venue, into a studio, where I stayed and created the works. It makes more sense, both ecologically and economically, for artists to travel individually and complete their work on-site, don’t you think? Using local common objects also offers an opportunity to learn about the everyday life of the city, an aspect of it that’s different from the Biennale. Besides, it’s always exciting to go out on the town to buy supplies. Whenever I create a site-specific work, I always hope that the use of such materials will reveal something connected to the memories of the local people.

The Japan Pavilion, completed in 1956, was designed by Takamasa Yoshizaka, a student of Le Corbusier. That’s one very distinctive piece of architecture. The marble floor, adorned with a geometric pattern in two tones, black and gray, is beautiful in an old-fashioned way, but the pattern compromises the homogeneity of the space, and the material feels too imposing in this day and age. In addition, the square room has a square hole in the centre of both the ceiling and the floor, which exposes the space to the outside air at all times. Although it’s really not a suitable venue for showing art, I am now on fire trying to figure out how to turn this environment around and make the most of it.

AR Why is the Venice Biennale still important, if at all? And what is the importance of showing there? Is it about visibility, inclusion, acknowledgement?

YM If the Biennale is important, that’s because many people think so, isn’t it? That’s why people still come to Venice from all over the world. I also think the Biennale is important, as a great opportunity to show my work to a larger, global audience (lol).

But we should question what a national pavilion means. To be honest, I have no intention of representing any country, be it Japan or not. For the first time in the history of the Japan Pavilion, I invited a ‘foreigner’ from a neighbouring country, Sook-kyung, to be the curator. We met each other and collaborated in an international context. I accepted to present my work at the Gwangju Biennale in Korea, which she directed, at a historical site where an anti-colonial movement took place during Japan’s imperialist occupation. She accepted a request from a neighbouring country with which her own homeland shares a complicated history. That’s because our relationship is a more personal one of sisterhood, independent from the intervention of the state. For me (and Sook-kyung), every single one of these facts is a statement.

AR When you make artworks do you have a specific audience in mind?

YM Not at all. I welcome anyone, whether it’s a child or a dog. I am especially happy when I get unexpected responses from such beings. I even have works in which birds participate, but you can say that the art I make is intended for humans rather than other living creatures.

AR Do you think there is such a thing as national art? Or is all art universal? Is there something that defines your nation’s artistic traditions? And what is misunderstood or forgotten about your nation’s art history?

YM I personally want all art to be universal. As I just mentioned, that universality isn’t limited to humanity either.

In Japan, however, the emphasis is more on the traditional forms (noh, kabuki, nihon-ga [Japanese-style painting], calligraphy, etc…) or subculture (manga, anime, etc…), with contemporary art being only a minor presence that barely exists out on the periphery of the culture. Although I agree that each of those traditional arts is a rather singular form in itself, it is a major problem that cultural administration and arts education in this country are still largely governed by those forms. In other words, the Japanese government has not been, and probably never will be, supportive of young, aspiring artists at all.

AR If someone were to visit your nation, what three things would you recommend they see or read in order to understand it better?

YM I would suggest taking a stroll in Akihabara, where I go to get electronic parts for my work. Located on the east side of Tokyo, the neighbourhood is now known as a hub of Japanese subculture including manga and anime, or otaku and cosplayers (it was the theme of the Japan Pavilion at the ninth International Architecture Exhibition in Venice). Originally, however, the district was dominated by stores selling electronic devices and components, which still dot the area around the train station. In the 1980s, innovations in electronics linked up with manga to form two new, post-internet visual forms: Japanese anime and otaku culture. Akihabara is a symbol of this development.

Akihabara’s origin can be traced back to the black market held on the scorched grounds in this neighboUrhood just after Japan’s defeat in World War II. The items sold there were diverted from the depos of Occupation Forces. Things not yet officially in circulation in Japan at the time were said to be in abundant supply. Vacuum tubes were one such product. Students at a nearby technical college put together an inexpensive radio with them, which turned out to be a huge hit. This marked the beginning of Akihabara’s Electric Town. In 1950, Japan quickly “saw the opportunity” in the war that broke out on the Korean Peninsula as a “special demand.” Nestling up to the Allies, with whom it had been hostile only very recently, Japan took full advantage of the situation. It thus sold vacuum-tube radios and electronic parts to the forces that had occupied it, for the conflict taking place on the land it once colonized, unabashedly achieving its ‘postwar reconstruction’. Akihabara can thus be seen as an emblem of Japan’s electronics industry, which bolstered the country’s prosperity until the bubble economy collapsed in the late twentieth century.

My work consists in analog tinkering with electrical parts. Fragments of the wisdom and techniques, passed down from the postwar black market to this day, live on in me in the twenty-first century. As I mentioned above, the story was not always clean. I feel a strange destiny here, though, for I entered the global art scene by working with those very knowledge and skills forged in Akihabara within the Cold War structure.

AR Which other artists have influenced or inspired you?

YM Nam June Paik, Takehisa Kosugi, and Shigeko Kubota. All three are artists from Asia, open to electronics, chance, and happenings. Kubota ended up marrying Paik, but the rumor is that she moved to New York to follow Kosugi (even though she got there before him!).

AR What, other than your own work, are you looking forward to seeing while you are in Venice?

YM Trevor Yeung representing Hong Kong. I am also looking forward to meeting and talking to different artists in person, which for me is one of the greatest pleasures of an international show. In addition to the art, I am very excited to cook and enjoy meals to my heart’s content, making my rounds to greengrocers, butchers, fishmongers and wine sellers around Giardini, whom I met during my last stay in Venice!

The 60th Venice Biennale, 20 April – 24 November