Camille Henrot at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, through 7 January

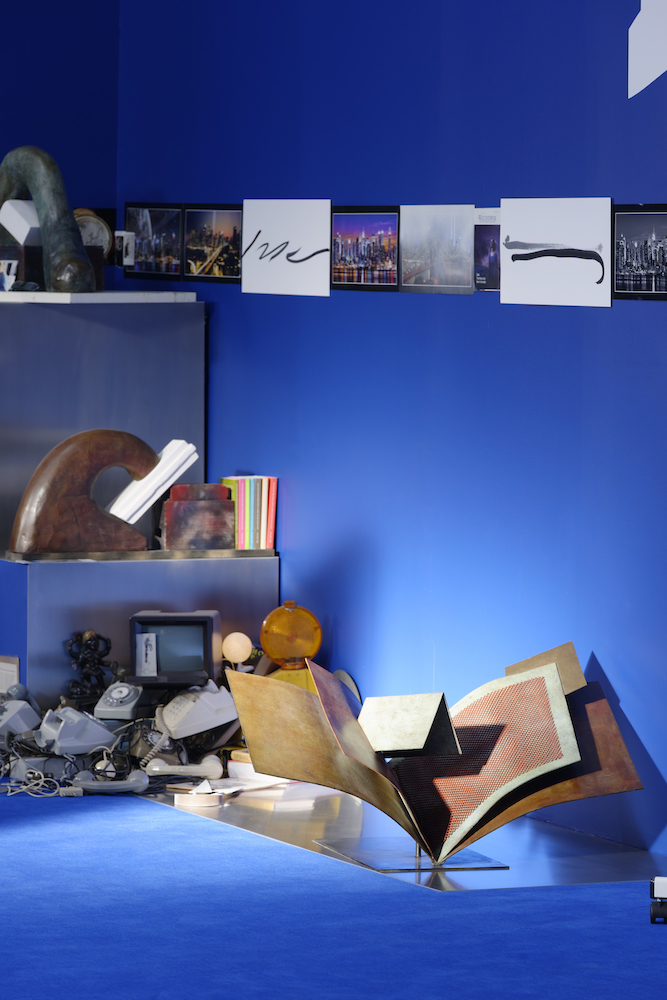

Since she began exhibiting in 2005, Camille Henrot has frequently highlighted shaky structures of knowledge: how we apprehend reality through self-invented means, from museums to the perfidious swamps of the Internet, to notions of time. Her signature work remains the dazzling video Grosse Fatigue (2013), a narrative of the universe’s creation unfolded via documentation of diverse historical collections appearing as a cascade of pop-up windows, and rapid-fire spoken word by poet Jacob Bromberg. For the New York-based French artist’s show last year in Rome, meanwhile, bronze sculptures – a sad figure from a Boticelli, a losing athlete, a drooping figure weeping while staring at a smartphone – embodied the disorderly and downcast qualities we associate with Monday, most people’s least-loved day. Now, taking her turn in the Palais de Tokyo’s ‘Carte Blanche’ strand, Henrot takes on a full week while doubling down on the digital undertow.

Split across seven spaces in the Palais’s cavernous interior, Days are Dogs also divides into seven ‘days’. The week, unlike the year – though we’re leaving out a fair bit of Egyptian and Babylonian inventiveness here, admittedly – is a manmade device built on dodgy foundations, not quite consonant with the Gregorian calendar, and seamed with residual mythology. In Henrot’s update, each day gains a presiding hashtag and each room mixes and recombines works by her and her artist friends, so that – for example – Wednesday becomes less the day consecrated to Woden or Mercury, or more lately ‘Hump Day’, and more associated with whatever contingent objects and images she and her coterie have assembled there. The Palais de Tokyo, please note, is closed on Tuesdays.

Toyin Ojih Odutola at Whitney Museum, New York, through 25 February

Anyone suspecting, in the light of Henrot’s project, that one primary role of artists today is to purposefully falsify might next turn to Toyin Ojih Odutola’s show at the Whitney, To Wander Determined, where the Nigerian-American artist’s sumptuous lifesize portraits in charcoal, pastel and pencil – with particularly virtuosic renderings of black skin – depict two aristocratic Nigerian families who never existed, framed in aspirational interiors. Ojih Odutola is notable in part for her hypermodern career path: she’s come up using social media, has been championed by musicians like Solange, and had her work featured in the background of the TV show Empire. But she’d be a standout figure for her drawings alone – pointedly presented here in a free-entry area of the museum – which deftly contest clichés of black servitude and reanimate the notion of the artwork as conversation piece, not least due to the ambiguities that swirl around her group portraits.

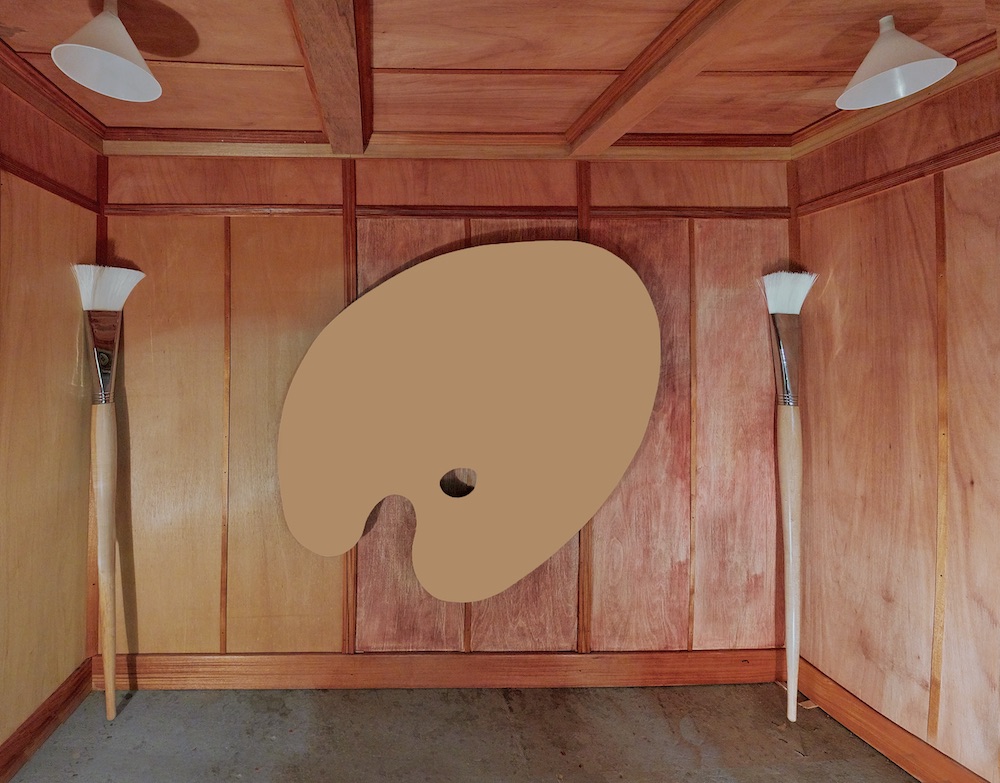

Andrew Grassie at Maureen Paley, London, through 7 January

More true lies: since he left the Royal College of Art in 1990, Andrew Grassie’s painterly approach has evolved from sedulously copying his own juvenilia, to painstakingly rendering gallery spaces, to the seven paintings in this show, which initially appear to be documentations of artists’ studios. Certainly they’re based on photographs, and certainly Grassie’s eye-straining facture in gouache suggests verisimilitude. But the wry Scot in fact set up these workspaces in his own studio before documenting them, presenting them as the lairs of a succession of imaginary artists: spaces in which, ironically given the man-hours Grassie puts into rendering them, no work appears to be going on. A surface truth, then, yet the epistemological ground beneath is weak. Part of the pleasure when Grassie debuts a new series is in the traditionalist thrill of his art’s high-grade fidelity; part of it is surprise, since he’s an artist who seems to design cul-de-sacs for himself and then, somehow, always reverses out of them (if only into a new one.)

Jessica Jackson Hutchins at Boesky East, New York, through 22 December

Jessica Jackson Hutchins’s ‘sloppy craft assemblages’, as the authors of her Wikipedia page calls them, have long linked to her life: she’s repurposed her old couches, and homely ceramics, and, when she became a parent, her children’s clothes started showing up in her art. That she’s now occupied with stained glass might naturally be traced to her biography therefore; and sure enough last year Hutchins visited an abandoned Christian Science church while location scouting for her participation in the 2016 Portland Biennial. She ended up filling in three missing panels in the church’s glass oculus, after which she took up a residency at a glass studio in her adopted hometown of Portland. Yet this show, The People’s Cries, with its brightly coloured, semiabstract and, yes, sloppy fused-glass pieces – including two 12m-long skylights – is also tinctured with the daily in other ways. Sandwiched between a multicoloured glass distension and its ceramic base is the written phrase ‘General Strike’, while further works (and the show’s title) refer to punk, upraised fists, and opposition movements both historical and contemporary. Hutchins’s everyday, then, is the same fissuring one we’re all grinding through, though maybe she sees it in brighter colours.

Lesley Vance at Xavier Hufkens, Brussels, through 16 December

Lesley Vance began as a painter of still lives whose process was gradually to work towards abstraction, closing down figurative references in taut, modestly scaled canvases until the image ceased to register, the painting a record of its mutation away from depiction. During the last three years, though, the forty-year-old Milwaukeean appears to have had a revelation: hey, why not just make abstractions in the first place. As her third exhibition at Xavier Hufkens showcases, Vance now freely improvises awhile and then responds to that, leading to luminous, looping compositions in jewel-box colours: viewers wanting something to grip onto might note allusions to a wealth of earlier painters, from Hans Arp to Georgia O’Keeffe to Hilma af Klint, while those who need narrative can try tracing back Vance’s intricate conundrums to the chancy place where they began, and those who want sheer lyrical complexity can proceed without caution.

Richard Jackson at Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, Paris, through 23 December

Contemporary art history, of course, brims with little eureka moments like Vance’s. For instance, to make a painting one doesn’t need a canvas or any kind of flat support, or a brush. One just needs paint. Richard Jackson, who as his French gallery puts it ‘considers that the nice couple made up of the paintbrush and the painting is a commonplace’, and whose rebarbative antics inspired a generation of West Coast artists, has demonstrated this since the early 1970s. He’s used windscreen wipers to apply paint; also doors, and a Vespa’s wheels. He’s made sculptures from painterly apparatus and sprayed and thrown paint onto all manner of objects – including, in his impishly monumental series of Bad Dog works, the facades of museums, over which said Clifford-sized canine is seen splashing piss-yellow paint. Now, following (apparently) several years of ‘consideration’, he’s reconstructing the Saint Germain bar La Palette – the name being not irrelevant, nor to its curvilinear shape – in an ‘homage to the old and kitsch world of the painter and his easel’. The bar is mechanised, and randomly sprays paint around the gallery; the title, delineating the act, is The French Kiss.

11th Bamako Encounters in Bamako, through 31 January

At this point, we realise we’ve been banging on about painting for much of this column. We’re not sorry – painting’s the best – but let’s switch media. Over in Mali, the Bamako Encounters is opening its 11th edition since 1994, which means photography, and in this case photography under the rubric of Afrotopia, aimed at countering the Westernisation of Africa by focusing on cultural contributions arising from within the continent. Expect, then, a monographic show for octogenarian London-based Ghanaian photojournalist James Barnor, who – aside from pioneering work documenting Africans in the UK – went back to Ghana and introduced colour processing there. Other projects include Justin Davy’s exploration of African music since independence, and Nigerian curator Azu Nwagbogu’s show dedicated to Afrofuturism.

Otto Berchem at Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam, through 23 December

You can learn a lot of arcana about codes from Otto Berchem. Did you know that American hobos had a set of signs for each other, eg a triangle meant a homeowner had a gun, a circle with two parallel arrows meant ‘scarper, hobos not welcome’? The Connecticut-born, Bogota-based Berchem used this language for a 2005 work in the Istanbul Biennial, and the interest in hierarchy wasn’t a one-off. Earlier this year he made a work with Amalia Pica, Mobilize (2017): a punning sculpture rendering a midair cascade – basically a mobile – of falling coloured papers that, neatly, could be read as relating to either of their codified practices. It recalls Pica’s interest in painful bureaucratic processes and turns an earlier video work by Berchem – Revolver (Universidad Nacional) (2013) – into a sculpture, while the title points to the politics underwriting the latter’s work. A while ago, Berchem created a chromatic alphabet, drawing on sources including the writings of Jorge Adoum and Vladimir Nabokov (who had synaesthesia), and Peter Saville’s sleeve designs for the first three New Order albums. In his fifth show at Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Dive for Dreams, Berchem partly continues a project of recoding iconic artworks through this alphabet, but his project isn’t a quixotic one. As an American living in Bogota, Berchem is concerned with centre and periphery and lopsided power structures, and his revisions might be seen as a symbolic claiming of agency; when, as here, he takes a well-known work like André Cadere’s multicoloured sticks and recasts them as brooms, he at once activates the political-metaphorical meanings of the cleaning implement – new broom, sweeping away corruption, etc – pointing, à la ‘mobilise’, to the necessity of dissent and of reshaping the balance of power, while, as ever, filtering it through eye-catching aesthetics.

Shaun Gladwell at Tel Aviv Museum of Art, through 24 February

A red thread through Shaun Gladwell’s career has been ‘horse substitutes’ – cars, motorbikes, skateboards – as well as heroism, masculinity and war. The Australian artist has, among other projects, spent extended periods in his country’s desert to make his series Maddestmaximus (2009), which involved Gladwell car-surfing, ie riding on the outside of a moving vehicle; and, for the 2016 video Skateboarders VS Minimalism, commissioning pros to skate on exact replicas of minimalist artworks (to a Philip Glass soundtrack, naturally). Now, though, Gladwell’s dealing with actual steeds. 1,000 Horses, being shown in Tel Aviv, appropriately links Israel and Australia, referencing the century-old Battle of Beersheba, in which the 4th and 12th Australian Light Horse Brigades, and the Allies, defeated the Ottomans – an event that triggered the British rule of Palestine, and is thought to be the last major battle involving soldiers on horseback. The works here, though, focus on the horses: videos and virtual-reality photographs of the horse’s life-cycle, and a 3D print of a damaged Roman equestrian sculpture, shifting the emphasis – appropriately, given Gladwell’s outlook – from domineering warrior to sacrificial equine.

Maria Hassabi at K20, Düsseldorf, 9 December – 21 January

And lastly, from galloping to, well, not: we all get slower as we get older, but Maria Hassabi has ambled ahead of the curve. After debuting in early-to-mid 2000s New York with performance works that consciously tapped the residual energy of the downtown scene (graffiti backdrops by Dash Snow’s crew, a focus on fashion), the Cyprus-born artist has since decelerated wildly. Nowadays her works, performable anywhere from theatres to Wall Street to the atria and staircases of MoMA (for PLASTIC, 2016), constitute successions of glacially morphing poses, barely mobile tableaux vivant; and indeed Hassabi’s central interest is in the relationship between the body and the image. (Alongside, clearly, the fact that we all move too fast and don’t stop to smell the roses.) At K20, smartly matched to the cool gratifications of the museum’s concurrent retrospective of Carmen Herrera, she’s presenting a variant on STAGING (2017). Initially performed at this year’s Documenta, it’s a solo of movements by Hassibi subsequently imparted to a quartet of dancers who, art historian/critic Rachel Haidu has written, ‘multiply her, fracturing a solo into multiple parts that can now touch one another, repel or entwine’. What’s being ‘done’, here, is sometimes no more than breathing – which, incidentally, is what Duchamp said he was ‘doing’ for the latter part of his career (even if it wasn’t quite true). Any sluggards looking to defend their inertia, here’s your line.

From the December 2017 issue of ArtReview

Learn to solve the Rubix Cube with the easiest method, memorizing only six algorithms.