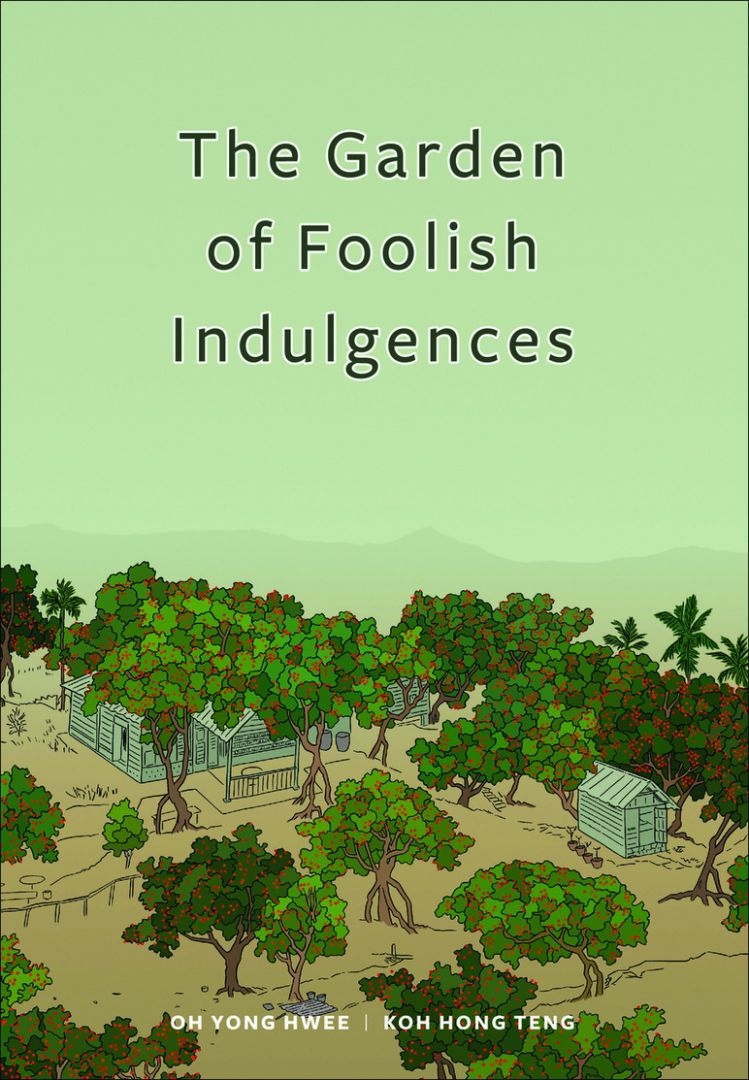

The garden in question in Oh Yong Hwee and Koh Hong Teng’s new graphic novel is Singapore. More precisely, it’s the multiple ways in which people have imagined the island over the years; how generations of immigrants have cultivated this land – both real and imaginary – and continue to do so today. Of course, there is also a literal garden: an orchard that thrived in early-twentieth-century Singapore. Owned and tended to by Han Wai Toon, a Chinese immigrant who came to Singapore to seek his fortune in 1915, the orchard attracts the attention of a present-day migrant, Ye Feng’an, a journalist with a Chinese-language magazine targeted at other recent migrants like himself. He and his wife, Yuxuan, have moved to Singapore’s English-speaking environment to give their young son a leg-up in the world. These two parallel stories of migration, set almost a century apart, bring into relief the stark differences, and some resonances, between various waves of Chinese migration to the city-state.

Han’s garden became a cultural institution for an emigré scene of Chinese artists and writers, drawn to Han’s cultivation of a refined, genteel space in the middle of the harsh tropics. As Feng’an digs into Han’s life and times, his own family is facing a minor crisis. Singapore isn’t turning out quite as they’ve expected: their son is picking up more Singlish than English; every day they face xenophobic microaggression; and they’re not crazy about the food.

This is where the novel is at its weakest: as a depiction of migrant realities. Poorly developed, the present-day characters drift blandly through their lives, and the reader, too, watches them passively, with little insight into their struggles and personal crises. Often, Feng’an and Yuxuan are rhetorical mouthpieces for the questions the novel is asking about migration. And that’s the main problem here: the novel lulls the reader into a bland social-realist drama, when it is really an exquisitely poetic meditation on the shifting meanings of Singapore over several generations. Through a complex series of motifs and metaphors, both literary and visual, the novel reaches a layered understanding of the island as an ongoing, constantly shifting patchwork of personal projects of nostalgia, homemaking and private aspiration.

This web of ideas resists the easy nostalgia that attends to cultural production around Singapore’s lost heritage. You’re reminded that even as we lament the passing of this rich space, the orchard was in itself a nostalgic, ultimately hollow reproduction of another way of life. A century later, Feng’an treks into the heart of the jungle, only to find a single, fruitless rambutan tree and a latrine.

There’s a similar critical intelligence to the artwork. Koh’s strategy is a clear and deliberate stylistic contrast between the present-day and twentieth-century narratives. For the most part, he opts for a simple, ‘talking heads’ style for the contemporary passages. It’s in the Han sections where the artwork blooms – the panels become richer, each frame filled with painterly strokes and details. It seems a predict- able pattern at first: something about the past feels richer, feels more real. But near the novel’s end, after Feng’an concludes his investigation into Han’s life, and deep uncertainty sets in about whether or not his family will remain in Singapore, Koh flips the script. There’s a sublime, silent series of panels set in a cold Singapore subway station. Angular escalators and stairways spread out like cold, grey foliage, with odd bursts of colour – a mural, a colour-coded subway map – catching the eye. Here, progress and development, the big enemies of nostalgia and heritage, melt into the same meaning-making exercises that have, the novel suggests, for a long time now, worked like complex algorithms at the heart of the city. There’s something moving in these moments: all change is part of a human impulse to work the land, to make it arable. Whether it’s Han’s tilling of the soil to give birth to poetry, or Feng’an’s family seizing on the opportunities of Westernised modernity, or the government’s relentless urban development, Singapore is an empty cipher to be constantly repurposed and rewritten.

From the Winter 2016 issue of ArtReview Asia