Shifting social values and non-Hindi films have driven a new golden age in Indian arthouse, but the sociopolitical climate has become increasingly worrisome

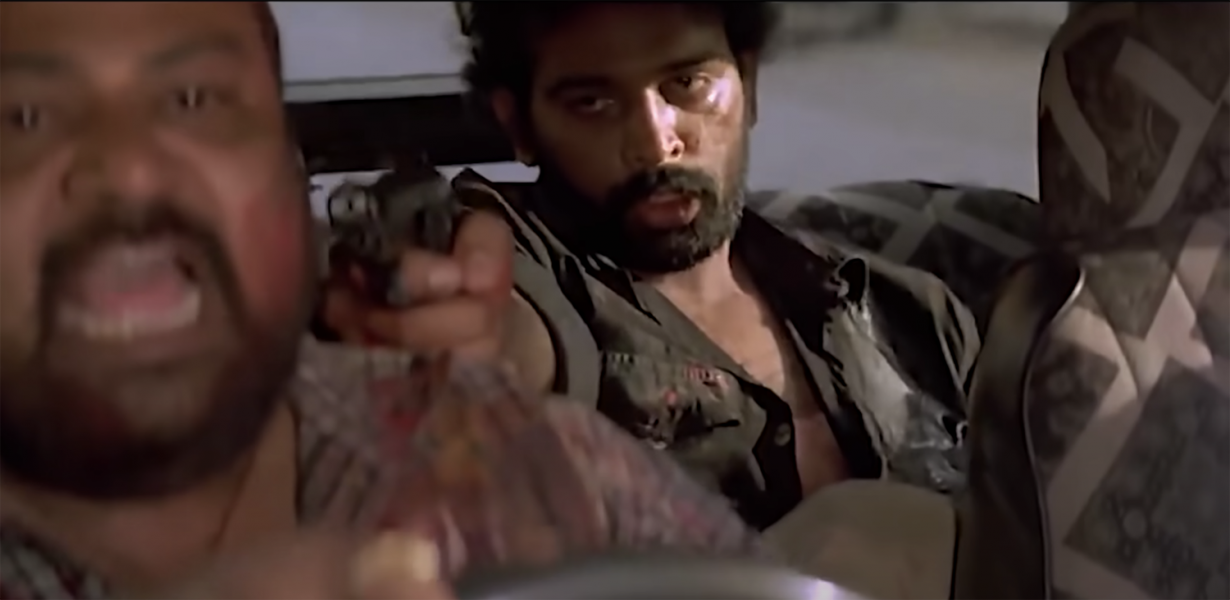

In 1998, the spark for the resurgence of an alternative to mainstream Hindi-language cinema (Bollywood) was ignited by the massive commercial and critical success of Ram Gopal Varma’s gangster drama Satya. Unlike the uber-rich backdrops of most Bollywood films, Satya tapped into the gritty underbelly of Mumbai, which until then had mostly found space in the films of Saeed Akhtar Mirza and Sudhir Mishra, icons of parallel, or new, cinema. Satya’s acceptance by mainstream audiences instilled hope in many budding writers, actors and directors who didn’t wish to tread the beaten path of conventional escapist cinema. One of the brightest talents to flourish post-Satya is its writer Anurag Kashyap, who has been championing novel and high-quality films ever since. With his directorial debut, Paanch (2003), Black Friday (2004), based on the Bombay bomb blasts of 1993, and the political drama Gulaal (2009), Kashyap has given Indian cinema some of its finest films. His Dev. D (2009) and Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) – an epic crime saga spanning several decades and generations – found a fan in Martin Scorsese.

The 2000s also witnessed another exceptional filmmaker, Dibakar Banerjee, who made a mark with his uniquely entertaining films Khosla Ka Ghosla (2006), Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! (2008) and Love Sex Aur Dhoka (2010), which captured the quirks and varying hues of the North Indian middle class like never before. Music composer-director Vishal Bhardwaj took Hindi parallel cinema by storm with Maqbool (2003), an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth set in Mumbai’s criminal underworld. Vishal would later bridge the gap between the mainstream and parallel worlds by employing popular actors in his acclaimed ventures Omkara (2006) and Kaminey (2009). The financial success of these films encouraged major studios and A-listers to back smaller films with rich and innovative content. Arthouse films like Dhobi Ghat (2010), The Lunchbox (2013) and Masaan (2015) perhaps wouldn’t have been able to raise capital before the twenty-first century.

In the previous century, films that strayed from mainstream narratives had to depend on the state-funded National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) for production and distribution. Meagre budgets enforced austerity in the production values of such offbeat films, which were stripped of the commercial tropes of popular cinema, including song-and-dance sequences. Steeped in realism, they came to be bracketed by media and film scholars as parallel cinema, a category also called new cinema. Before parallel cinema snowballed into a wave across all Indian languages during the 1970s and 80s, the roots for its genesis were being put down in Bengali-language cinema by filmmakers such as Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen, who discarded the flamboyance of popular cinema to embrace simplicity inspired by Italian neorealism specifically, and European arthouse films in general. The Indian establishment (government) at the time was also in favour of producing quality films that could match the technical brilliance of international films while at the same time reflecting the social realities and cultural history of the country’s heartland. This support via NFDC led to the emergence of several talented filmmakers who were provided access to funds and a license to experiment with aesthetics, form and style in their work. Among these new auteurs were Mani Kaul, Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G. Aravindan, Buddhadeb Dasgupta and Girish Kasaravalli.

By the mid-1980s, parallel cinema’s flame had begun to flicker owing to the waning interest of producers, distributors and exhibitors in backing smaller films. One significant reason for this was that most of these films continued to mirror the problems of the dispossessed and marginalised, whereas the burgeoning middle-class cinemagoers were in search of stories that resonated with their aspirations and social realities. Additionally, the advent of television had lured many alternative filmmakers and ‘serious cinema’ actors with diverse content and substantial money.

During the 90s, there was a massive drop in the number of films produced by NFDC. However, stalwart directors persisted in making quality films without compromising on their ideals to represent unheard and often suppressed voices from the fringes of society. A few gifted filmmakers like Shaji N. Karun and Rituparno Ghosh also found their feet, and in doing so, helped keep arthouse sensibilities alive.

Today, with the expansion of multiplex theatres across the country and the outburst of OTT platforms a few years ago, parallel cinema seems to have found a new stable home and many takers. Despite Hindi being the most widely spoken language in the country, it is the regional film industries that are spearheading the content revolution in Indian cinema. South Indian filmmakers like Vetrimaaran, Dileesh Pothan and Lijo Jose Pellissery have successfully managed to integrate their brand of realistic cinema into the mainstream. Malayalam-language actor Fahadh Faasil has become a national star by appearing in cult films of the past decade such as Maheshinte Prathikaaram (2016) – an atypical revenge tale that subverts the conventional notions of masculinity so often found in mainstream cinema – and Kumbalangi Nights (2019), in which Faasil’s character, Shammi, is the acme of perverse and pathological masculinity. The commercial success of such films that challenge cultural stereotypes, traditional ideas of gender roles and patriarchal attitudes is a testament to the evolving tastes of the masses.

But for filmmakers who dare to experiment with content, the sociopolitical climate in India has become increasingly worrisome. A draft Cinematograph (Amendment) Bill 2021 empowers the central government to order recertification of an already certified film following receipt of complaints. The film fraternity has come together to protest a bill that would render them powerless against the state. In India, artists and especially filmmakers have always been pricked by censor authorities. Anurag Kashyap’s Paanch never got a theatrical release, as the Central Board of Film Certification objected to the film’s violence, the depiction of drug abuse and crass language. The Indian government this year has also imposed regulations to monitor and regulate OTT content more ‘closely’. With such clampdowns on freedoms of expression, independent filmmakers like Sanal Kumar Sasidharan, Sajin Baabu and Gurvinder Singh might have to rethink their content strategy in the years to come.