When we think of Luc Tuymans, hot colour and humour aren’t the first things that come to mind. For over 30 years the hugely influential Belgian painter has used a washed-out palette to prowl around trauma, locating it in details, peripheral views, seemingly anonymous scenarios. He’s explored a multitude of subjects, often opening onto the dark operations of power – the Holocaust, colonialism, corporate aesthetics, even Disney – while simultaneously querying the vitality, or otherwise, of painting itself. For all their atypical blues and reds, his seven new canvases – a self-described ‘joke on Modernism’ with colonial undertones – are unsentimental, ironic and probing enough to fit right in.

They’re based on stills from the end of The Moon and Sixpence, Hollywood’s 1942 version of W. Somerset Maugham’s novel about painting and death in the South Pacific, a black-and-white film that bursts into bright, redemptive colour in its final stages as it unveils the final work that the roguish painter created. For the mordantly amused Tuymans, Hollywood’s first attempt to fix the image of the modern artist completely misses the point of painting – and of painters. (Notably, he appears in the new paintings himself, if spectrally: a skulking reflection in the TV screen he photographed with his iPhone.)

Yet the septet is also concerned with issues rarely discussed vis-à-vis Tuymans’s paintings: touch, qualities of projected light and foreground vs background. The artist, for all his theoretic rigour, is lastingly concerned with medium-specific issues, but in interviews he usually emphasises his art’s conceptual exoskeleton. Here, as he prepared to bring his new work to London, Tuymans sat over coffee and cigarettes in his sunny Antwerp studio and talked about painting – his anxieties in front of the canvas, thinking slow and painting fast, the medium’s purported ‘weakness’ – and, additionally, about van Eyck, parrots, filmmaking and why he avoids looking at his own art.

ArtReview

What was the starting point for these new paintings?

Luc Tuymans

James Lingwood of Artangel asked me to make a painting for A Room for London [Fiona Banner’s Thames-side riverboat, located on top of the Southbank Centre for the duration of 2012 and modelled on Le Roi des Belges, the boat Joseph Conrad captained on the Congo trip that inspired his 1899 novella Heart of Darkness]. There is a line in Heart of Darkness that suggests Kurtz made paintings. Thinking about that, and about the exotic, I remembered the end of The Moon and Sixpence, starring George Saunders, about the Gauguin-like painter. Not a great movie. It comes across as romanticism, the immoral human absolved in the end by his art [in the film, a stockbroker, played by Saunders, gives up his job and family to become a painter in Tahiti]. Hollywood made the cardinal mistake of going for the humanity in it, whereas being an artist, making art, is inhuman. And when his painting is revealed at the end, it’s all fake Gauguins – extremely kitschy. Painting that, that’s my joke on Modernism.

There’s certainly a strong sense of remove from the modernist moment: we’re looking at a cheap fake, through a screen, repainted. I saw six of the seven paintings recently in Zagreb’s HDLU, where they were shown around the upstairs balcony of the institution’s circular gallery. The colour appeared out of nowhere. As in your forthcoming show at David Zwirner in London, you’d titled the exhibition Allo!…

LT: They’re at once the most and least colourful paintings I’ve ever made. Because they just consist of a couple of colours. Mostly when I work with tonality I need more colours, so it’s a very raw aspect. I also wanted to work with the specific quality of projected light, and with the contrast – normally I start with the lightest colour and adjust the contrast, and here I had to go first into the contrast, then adapt the colours – and with the element of surprise. The title comes from a parrot. There’s a bar nearby where I go where mostly marginal people go – they don’t know me – and they used to have a parrot that would say, when you went in, “Allo!” That’s the surprise. You wouldn’t expect these colours from me.

I wondered, also, how significant Hollywood was to the choice of subject. Your 2010 Corporate show at David Zwirner in New York explored the deep history of corporations; your 2008 show there, Forever, The Management of Magic, considered the iconography of Disney. Do these subjects all hang together – dream factories, power structures, representational fronts?

LT: In a sense they do, of course. Forever came out of a whole line of thought whose starting point was the utopian. It began with Jesuits – which is still utopian as well as religious and humanistic – and out of that came the idea of making something about Disney, the topography of fantasy, determining what Disneyland is now and going into his topic of the ideal city. But the show after that, Against the Day [at Wiels, in Brussels, in 2008], named after the Thomas Pynchon book, dealt with the triviality of ‘now’ insofar as its source images often came from websites that were still under construction and dealing with virtual reality, Big Brother, YouTube. And in the Corporate show, the starting point was actually the light. That becomes more and more important.

In the past your painting practice has been characterised in terms of deliberate weakness, failure. You’re discussing different things today.

It’s more interesting to go beyond this idea of failure

LT: That was a discourse made by people like [museum director and critic] Ulrich Loock, coming out of the Frankfurt School, and the idea that the failure of painting is evident. [Loock wrote, for example, that ‘…his mourning recommences with painterly representation itself, setting about to bring it to an end, constructing its failure’.] But of course it’s not. It’s more interesting to go beyond this idea of failure. And actually not care, because this discourse – that painting would be dead or alive – is very stupid. Painting and photography is no longer an issue: it might have been in the days of [Gerhard] Richter and Vija Celmins, but that’s not interesting. Also my art doesn’t deal with art, it deals with the things I see, and largely comes from reality and from a different branch – a regional one, in the sense that we’ve created the best painter in the Western hemisphere: Jan van Eyck. Nobody could top that. So from the start, as a painter in this country you would be traumatised.

So, ‘painterly representation’…

LT: Representational imagery is my kickoff to make the painting, but that’s not nearly as important for the viewer – that he or she should know what it’s about. I gave the source, always, because I thought it would be wrong not to, but it’s just an accompanying element. There has been so much written about the work that now it’s time to look – to look at its painterly qualities.

So do you feel the discourse around your work has sometimes been unhelpful? Because it means someone might look at a painting of yours – knowing that, say, when you painted a blank-faced figure in The Architect [1997] it represented Albert Speer – and think, ‘OK, this is an anonymous object or subject: I assume it has some grim history attached to it.’

LT: I don’t say it’s negative, because it’s helped people looking at it and helped my career, probably, but that’s not what the painting is about. Visual art works with the visual, and that’s the first element that should be apprehended.

Can you have it both ways, though? You’ve said you’re an extremely conceptual painter, but at the same time you want people to look at the materiality, the facture.

When people ask me why I still paint, the standard answer is: ‘because I’m not naïve’

LT: Look at [van Eyck’s] The Arnolfini Portrait. That’s a highly conceptual painting, but you can also look at how it was made. These things are self-evident. It was always my conviction that painting was the first conceptual art. Go back to Lascaux: those paintings were not for everybody, they were for the initiated: you had to crawl in. It was never naive. When people ask me why I still paint, the standard answer is: ‘Because I’m not naïve.’ When I first showed, I was very aware of the historical moment I was in, and it was with a gallery that specialised in postconceptual art, so the minute the show opened, it had a different audience, and was perceived not as painting but as image-making.

But it seems as though some people have interpreted the way you apply the paint – the scratchy, speedy style – as part of the conceptual armature of the work.

LT: Well, sure, I once said – and it’s true to a point – that once I know what I’m going to paint, I also know how I’m going to paint it. I disconnect those two stages. The stage before doing the painting or paintings – the conceptualising – takes months. Executing the painting takes a day. At that time, I don’t have to consider the idea, the concept. The brain shifts to my hands.

Do your paintings ever surprise you when you’re painting them?

LT: Always, in that I have this extreme nervousness before starting. The first three hours, although I know what I’m doing, are like a blank, like hell. And once the image starts to come together, that’s more than midway in, and that’s where the pleasure actually starts. Why the blank? Because of the element of intentionality. People forget that, and that’s why I stress looking: at the intensity of things. And that has to do with an element that’s highly reduced to timing and precision. There are two intelligences: the brain and the physical one. When the physical one is operating, that’s something no one will ever be able to conceptualise.

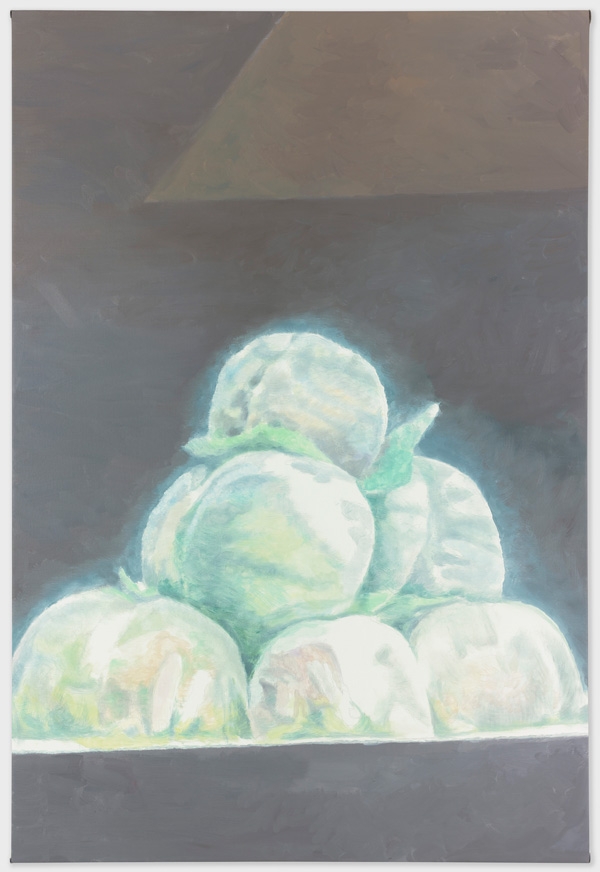

These issues – light, imagistic force – are traditional painterly concerns, whereas your work has been interpreted as self-reflexive critique. Still Life [2001], for example, your huge yet insubstantial ‘response’ to 9/11 in the form of a vast depiction of fruit and a water jug, did seem very much about painting’s inadequacy. Does the way you’re talking about your work now reflect the way you’ve always thought about it?

LT: There are things you can see; I don’t think I have to explain them and therefore I explain the rest. Which was stated very nicely by the first journalists, and then turned back at me – if I don’t speak about my paintings, they can’t look at them. It was perceived as arrogance. So it’s never good.

But you do, in interviews, often sound confident about how your paintings are going to operate: take your 2004 conversation with Julian Heynen, for instance. [Here Tuymans said of one pairing that ‘when the paintings are combined like that, you come right up against the possible banality of the painting and the ‘banality’ of your own ideas. The picture simply cannot be seen as an icon.’]

LT: That’s maybe a little bit of an overestimation on my part, and not a correct one. But of course there is this perception of how the work could basically function. I did a test once. In 1992 I was giving tours of a show: first I had people look at the work, then explained what they saw. In front of Our New Quarters [1986, painted from a postcard of the Theresienstadt death camp that was given to inmates to send home], they saw a depiction of decay, a prison, military colours, Eastern Europe…

On the one hand you have a painting and title like Gas Chamber [1986], on the other, less revealingly, DDR [1990–1], which depicts an athlete who worked as a resistance fighter during the war, and didn’t survive. How do you calibrate how much information to release around a work?

I don’t like the type of art that stands in a corner and then once in a while says something intelligent

LT: I never did that, and that’s maybe one of my problems. I’ve been generous with information because I thought it was part of the service, and also to demythologise things because I don’t like the type of art that stands in a corner and then once in a while says something intelligent. Most of the things should be communicated, then you can actually look.

The problem is that there’s now this culture of reading rather than looking, isn’t there?

LT: Yes, a big problem in the artworld right now, and that’s why paintings are virtually no longer included in real big art events like biennials and Documentas. And when they are, they’re architecturalised in the sense that they can no longer be perceived. And this is a great thing, because that reflects the fact that painting is extremely particular, ultimately visual. So the discourse fails, it puts painting back in an antagonistic position, which was my starting point.

Isn’t it possible that, having made works that seem like they can be unlocked by language, you’ve inadvertently contributed to the shift from looking to reading, encouraged it?

LT: Yeah, well, they’re two separate things and they always remain separate. What I say about my things is just that, and it can be valuable or not; it’s not the ultimate truth. When I disappear, these things will stay around, and a different perception will allocate itself to them. And this can happen now. It depends on the obstinate way a viewer looks at it.

Do the paintings ever change their meaning for you?

If I’m confronted with a work of mine while eating in a collector’s dining room, I’ll put my back to it

LT: Uh [laughs]. That’s an interesting question. It’s quite difficult because I have a very good memory: in front of a painting from nearly 30 years ago, I would still see from the first glance where I started with the first brushstroke and ended with the last one. So in that sense the meaning is the same. It’s also why I don’t keep any of my works, which is not very smart, but I don’t have this fetishistic element in me. I also never kept my toys; I just gave them away to other kids. And if I’m confronted with a work of mine while eating in a collector’s dining room, I’ll put my back to it.

Though much of your work has been inflected by the filmic image – and you’ve made films yourself – the Allo! paintings are arguably the closest you’ve gotten to paralleling cinema in paint. The movement they enact, which progressively shows the figure entering the space where the painter’s works are, and then cuts away to the paintings themselves and to an African statue, is like a camera movement. Do you think that your decidedness as a painter, decisions already made by the time you reach the canvas, comes from filmmaking?

LT: To a certain extent it does. I stopped painting temporarily at the end of the 1970s/beginning of the 80s, because it was too suffocating, too existential, and it didn’t leave room for distance. And then by accident I started to work with Super 8, then Super 16 and in the end 35mm, which is very expensive, so you have to think carefully about what you’ll film. And then coming back to painting, my whole knowledge of the visual was informed by things that are nothing to do with painting: closeups, how you edit an image. The first painting I made after was La Correspondence [1985], which is a highly conceptual image. So, for sure, that’s a big influence.

Can you see yourself ever making another film?

LT: It’s still in my underbelly to do that. It can’t be combined with painting. But then it would be informed the other way around. A young filmmaker recently did an all-night interview with me, and we agreed we’d both be very bad photographers, because photography is in the moment. We would both be decisively too late. With both filming and painting, it’s not about capturing the image. It’s all about the approach.

This article originally appeared in the October 2012 issue.