Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from the 36th Bienal de São Paulo to ‘Global Fascisms’ at HKW, Berlin

36th Bienal de São Paulo: Not All Travellers Walk Roads

Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, São Paulo, 6 September 2025 – 11 January 2026

Faced with the Bienal de São Paulo’s notoriously tricky Oscar Niemeyer-designed pavilion (all wide open spaces, ramps and curves), Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, curator of the thirty-sixth edition, has turned to the idea of estuaries and rivers for inspiration – both in the exhibition’s formal design and concept. He promises as few walls as possible and new commissions from the likes of Ana Raylander Mártis dos Anjos, known for her installations of found textiles, which will stretch the height of the building. The water motif also allows Not All Travellers Walk Roads – the title taken from a poem by Conceição Evaristo – a fluidity in its approach, encompassing art, performance and poetry, in which cultures and contexts ebb and flow against each other. The likes of Frank Bowling, Huguette Caland and Lynn Hershman Leeson will run alongside locals Gê Viana, Manauara Clandestina and Rebeca Carapiá. Not All Travellers Walk Roads follows some of the strongest currents in curatorial thinking (‘the most pressing issues of our time’ Soh Bejeng Ndikung noted): ecology, postcolonialism, a fluidity of personhood, the idea of attention; how the curator navigates these with a new sense of urgency remains to be seen. Oliver Basciano

Okayama Art Summit 2025: The Parks of Aomame

Various venues, 26 September – 24 November

“Things are so convenient for us these days, our perceptions are probably that much duller. Even if it’s the same moon hanging in the sky, we may be looking at something quite different. Four hundred years ago, we might have had richer spirits that were closer to nature,” observes a dowager in conversation with Aomame, a fitness instructor who moonlights as an assassin, in Haruki Murakami’s 2011 novel 1Q84. This longing to reconnect with nature seems to have inspired ‘The Parks of Aomame’, this year’s Okayama Art Summit for which Phillipe Parreno is artistic director. Drawing a semi-fictional path for visitors, the summit, which ‘is not simply a visual art exhibition’, will unfold across the city’s urban parks and overlooked spaces. Aomame, who finds strength and clarity in her solitary encounters with the natural world, becomes a guiding spirit for this project, and just as she finds comfort in reminding herself of her existence between sky and earth amid the concrete jungle of Tokyo – a means of anchoring herself as she navigates parallel realities – the summit reimagines Okayama as a site of balance between the organic and the constructed. Over 30 international artists, architects, musicians, writers, scientists and thinkers (including Shimabuku, Rachel Rose, Mire Lee, Holly Herndon & Mathew Dryhurst, Sou Fujimoto and Mariko Adabuki) will form a ‘guild’, transforming Okayama into a ‘laboratory’ where imagination and daily life coexist. Expect to find subtle changes to the city’s infrastructure and street furniture, and even ‘character-inhabited zones’, that suggest a slippage between parallel realities – where ‘the line between art-event and daily life will become blurred’. Fi Churchman

Hayv Kahraman: Ghost Fires

Jack Shainman, New York, 11 September – 25 October

As a teenager in the early 1990s, Hayv Kahraman fled the first Gulf War in Iraq and arrived in Sweden as an undocumented refugee. In the mid-2000s, she went on to study at the Academy of Art and Design in Florence, Italy. There, immersed in the work of the Old Masters, she picked up a visual vocabulary that she would combine with techniques from Persian miniature painting to craft a body of work centred on an iconlike female figure. At the start of Kahraman’s career, this figure represented what the artist called ‘a colonised body’, one that was ‘taught to think and believe that… white European art history was the ultimate ideal.’ Since then, this body has evolved to encompass a wide range of expressive forms, which Kahraman employs to explore memories and feelings of difference and alterity. In Ghost Fires, her fifth exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery, her icon appears again in oil and acrylic paintings on linen, both alone and in legion. Here are tempests of marbled paint raging around a tribe of larger-than-life women, entangled in each other’s hair and entrails, their bodies athletic and unabashedly sensual, their limbs at once supple and disarticulated. In response to the recent Los Angeles wildfires, Kahraman – who now lives in the city – has opted to ‘burn’ away the irises and pupils of these figures, leaving a sheen of electric white in their place. But she makes fugitive eyes reappear like offerings in some open palms. Jenny Wu

18th Istanbul Biennial: The Three-Legged Cat

Various venues, First leg: 20 September–23 November

The 18th Istanbul Biennial, Lebanese curator Christine Tohmé’s The Three-Legged Cat, opens the first of its tripartite editions – or ‘legs’ – later this month. ‘Resting on three legs from 2025 through 2027,’ the statement goes, ‘the 18th Istanbul Biennial is thoroughly feline. It secures its footing by stretching in time, following a rhythm nourished by conversations, gymnastics, and incessant news streams’. Just like my cat does. Tohmé’s opening exhibition is, thankfully, packed with talent and particularly that of the Global Majority – from Haig Aivazian and Mona Benyamin to Riar Rizaldi and Natasha Tontey. There’s Marwan Rechmaoui’s cod-scale models of urban settings and cartographic landscapes, upending the idea of doll houses or domestic rugs respectively. Or Merve Mepa’s metallic installations which present like archeological sites of computer hardware networks, steel poles snaking above heads and down to join behind moving-image screens like nodes. And Ola Hassanain, whose The Watcher (2025; currently on view at Kunstinstituut Melly) fills one side of a room with a mud-bank, held in place by tarpaulin bulging taught under the weight. Spatial translation, across all, would appear to hold the key. Given that the biennial’s organisers – Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (İKSV), who made a dog’s dinner of the curatorial election process – were met with resignations and boycotts, they’ll be happy to get on with showing some actual work. Whether The Three-Legged Cat can claw back its reputation, is another question. Alexander Leissle

Global Fascisms

HKW, Berlin, 13 September–7 December

The use of the term ‘fascism’ has become a commonplace in recent years. It’s an accusation that’s increasingly thrown at those right-wing politicians and political parties who have turned to forms of nationalist populism; with voters in Europe increasingly turning to the parties of the right – often those campaigning on anti-immigration and Culture Wars platforms – the label is being bandied about with abandon, none more so than in Germany, where the right-wing AfD continues to draw voters away from the old parties and faltering political consensus. Where such right-wing populists are in fact ‘fascists’ is a matter of debate, since the clearest examples of actual fascism are those of Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. And yet, while totalitarianism might not quite have arrived, many on the left and centre of politics see growing authoritarianism, ideologies rooted in ideas of ethnic exceptionalism, the use of executive power by autocratic leaders to sideline both the rule of law and parliamentary democracy, as tendencies that set alarms bell ringing. ‘Is Fascism Coming to America?’ screamed a Newsweek headline last year. If it quacks like a duck, then…? And if those are the criteria, then maybe they’re not just Western, but probably global; is Narendra Modi’s India tilting towards fascism? Is Iran an Islamo-fascist state?

Into this confusion steps HKW’s Global Fascisms, a fifty-artist international group show whose declared aim is to ‘understand fascism not only as a historical phenomenon, but also as an ongoing global threat… manifesting in diverse political, cultural, and social contexts today’. The focus, it seems, will be on how political attitudes find aesthetic shape. So from the artists so far announced – including Maria Lassnig, Rooee Rosen, Jane Alexander, Mimi Ọnụọha and Chulayarnnon Siriphol – one might expect a fair few works grappling with questions of patriarchy and gender conformism, the individual versus the collective, technologically-driven surveillance culture, and how to make art in contemporary societies still marked by censorship and repression. Whether all that adds up to fascism or not, it all sounds bad enough. Art, HKW’s notes state, is ‘not only a medium for reflection, but an active force in challenging authoritarian aesthetics and ideologies’. Let’s hope so. The downside of this, though, might be a lack of real reflection on why so many voters appear to have rejected the old political consensus, what their motives might be and how artists might engage with them. It will be interesting to see if Global Fascisms can meet that challenge. J.J. Charlesworth

Lee Bul: From 1998 to Now

Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul, through 4 January 2026

From the 1990s, a score of anime releases in Japan put the transformation of the female body centreplace. For example, Sailor Moon – in which seven teenage girls channeling the energies of the solar system battle dark forces of the universe – sees these girls transform into lethal weapons, dressed up as they are in heels and miniskirts and immaculately applied cosmetics. And whereas Sailor Moon reached mainstream popularity, works like Battle Angel Alita (1992) and Ghost in the Shell (1997), the latter based on Masamune Shirow’s manga, started to gain a cult following: both featuring women that had undergone biotechnological mutations and cybernetic upgrades in cyberpunk dystopia-fashion. It is on these waves that Lee Bul rides her well-known Cyborg sculptures (1998–), and it’s this series that marks the entry point to her mid-career retrospective Lee Bul: From 1998 to Now at Leeum Museum of Art. In the series, white silicon figures, adorned with mechanical gears and dressed in tight bodysuits, have smooth limbs cut short, heads absent and hourglass torsos truncated, at once idealised and deformed. At the centre of the exhibition will be the installation Mon grand récit, an ongoing project Lee has developed since 2005, comprising miniatures of spiraling highways, neon billboards and buildings cascading from a towering, crystalline mountain, evoking a futuristic post-apocalyptic metropolis. There will also be more recent work like Willing to Be Vulnerable (2015–16), a monumental, zeppelin-shaped balloon covered in thin metal foil, that hints at the fragility of lofty ambitions; in 1937, the Hindenburg disaster saw a hydrogen-filled zeppelin burst into flame, killing 36 people, and putting an end to the era of commercial airships. Yuwen Jiang

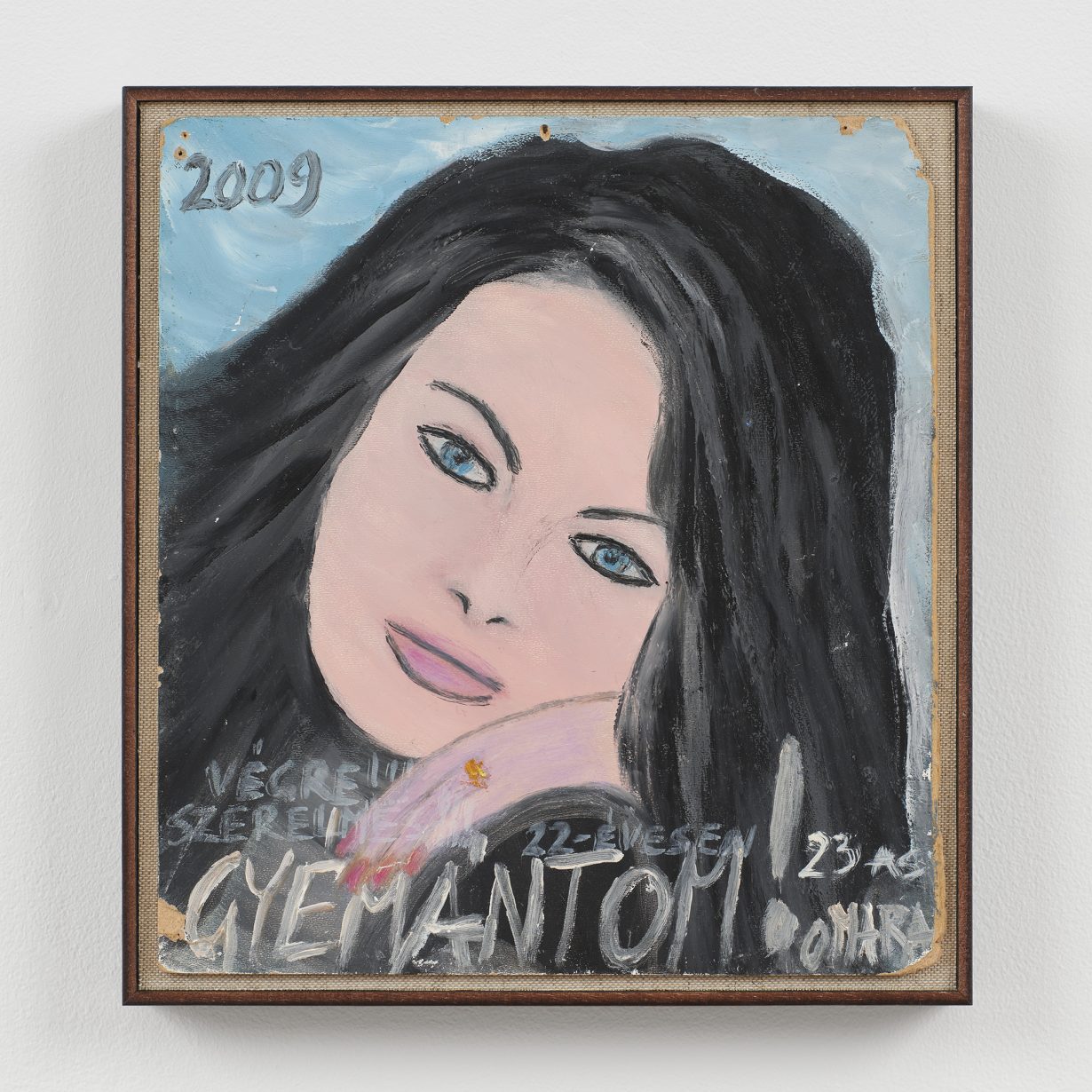

Omara Mara Oláh: Guess what, I’m still here

Margot Samel, New York, 5 September – 4 October

Guess what, I’m still here, the first US solo exhibition of works from the estate of the late self-taught artist Mara Oláh (also known as Omara), draws its cheeky title from an eponymous 2009 self portrait in which Oláh throws us a piercing look over her right shoulder. In this painting, the artist flaunts kohl-lined eyes and rouged lips, and the blurring effect of her brushstrokes create a visage reminiscent of 1990s glamour shots. This is the self-portrayal of a woman who, by the time she began making art at age 43, had been well-acquainted with poverty, prejudice and grief, belonging as she did to the Roma community in Hungary, a community that was and remains strained by the intergenerational effects of segregated schooling, housing discrimination and lack of access to medical care. Oláh’s work at Margot Samel includes paintings and photographs; the artist intervened in both mediums using bold handwritten text. On an oil-on-fibreboard portrait of her daughter, she wrote, ‘Végre!!! Szerelmes!!!’ (‘Finally!!! In love!!!’), while a gold engagement ring runs around the young woman’s finger. Also included in the show are framed arrangements of paintings on fragments of cigarette boxes – a miniature seascape, the slurry bodies of lovers melting into an embrace – each signed ‘OMARA’ in confident capital letters. Before she passed away in 2020 at the age of 75, Oláh made a name for herself not least by exhibiting in the first Roma Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale and opening the first museum dedicated to Roma artists in her Budapest apartment. Jenny Wu

Mika Tajima: Anthesis

Pace London, through 4 October

Mika Tajima’s sculptures and wall-based works complicate the sensory imagination. At her latest solo exhibition, this will include Pranayama (2024), a jagged lump of rose quartz sat inelegantly on a plinth; look closely at one of its faces, and you’ll see a small, glass valve has been cut into the surface – it’s the shape of a Jacuzzi jet nozzle. There will also be a series of abstract wall-based colour works, the Art d’Ameublement series (2011–), titled after Erik Satie’s 1917 ‘furniture music’, which present slushy-like gradients of sugary pinks, purples and yellow acrylic sprayed beneath supersmooth thermoformed plastic sheets. So far, so good-vibes promised. But what will we actually be looking at? The title Pranayama (2024), for example, is a term referred to in translations of the Bhagavad Gītā as the process of breath control – perhaps that’s what the valves are for? The Art d’Ameublement works are each named after locations – Telok Sebrang, for example, shares a name with a fishing village and beach resort in Malaysia. So looking at them might perhaps be a process of de-abstraction, of assuming or imagining form. A new series, Negentropica (2025), is said by Pace to feature iris flowers arranged in carved black marble boulders, illuminated in ultraviolet light and preserved by chemicals. All together, Tajima probes an unsettling notion, that stillness – which we increasingly pursue in life – is also a kind of trap, a sterilisation of the natural world, a death. Alexander Leissle

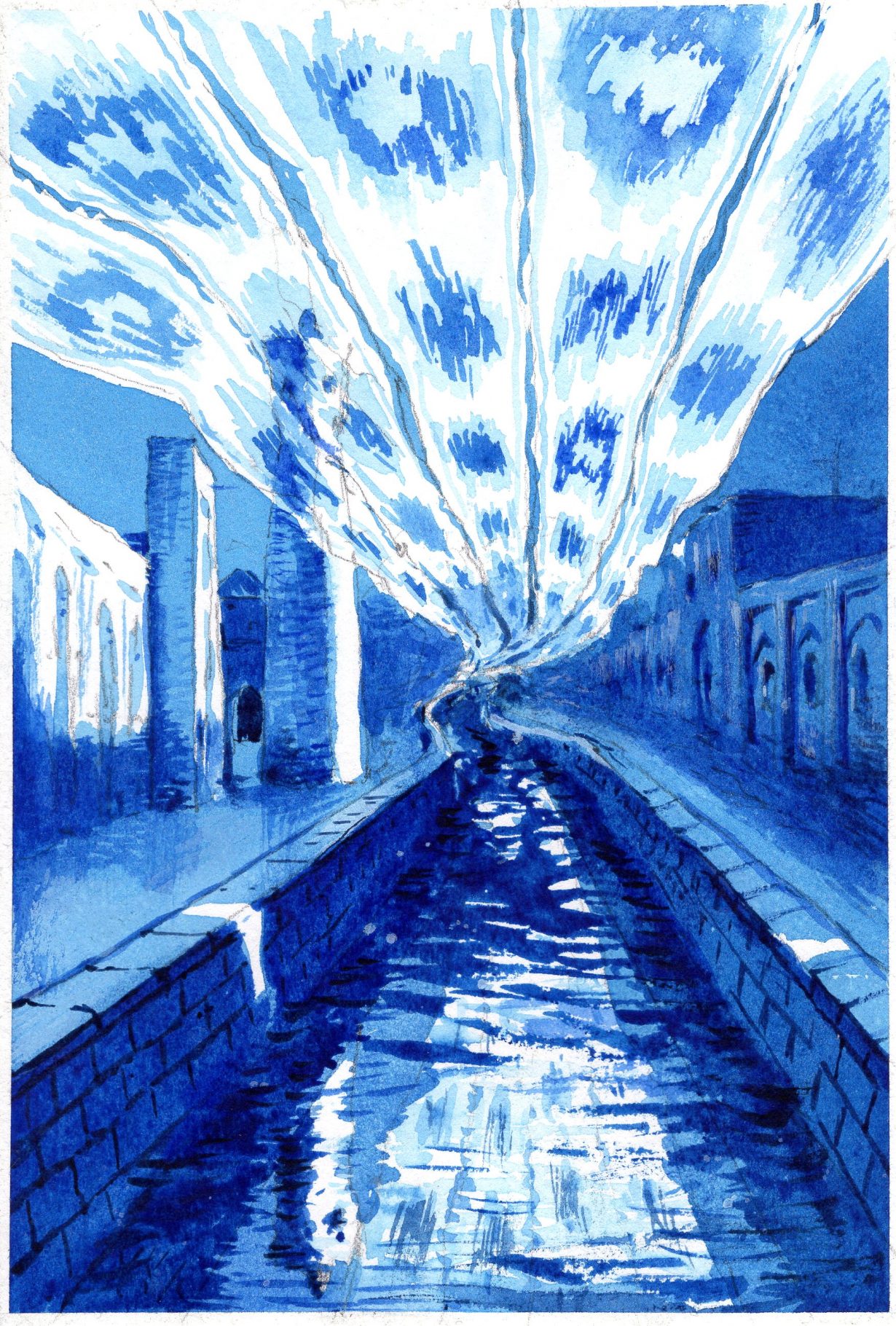

Bukhara Biennial: Recipes for Broken Hearts

Various venues, 5 September – 20 November

The healing power of food has a long history. In Greek mythologies, ‘ambrosia’ (the food and drink of the gods which some scholars consider to be honey) is said to possess cleansing powers and confer immortality upon consumption by humans. And in Chinese the saying goes that ‘there’s nothing a meal of hotpot can’t fix’ (although this was only viable after chili peppers were introduced to China from the Americas by the Portuguese). My personal favourite after a rough day is miso soup with garlic bread. Recipes for Broken Hearts, the theme of the inaugural Bukhara Biennial, curated by Diana Campbell, takes inspiration from the country’s own legend of culinary therapy surrounding the tenth century polymath Ibn Sina, who is said to have invented the staple Uzbek rice-based dish, palov, to mend both the body and the heart of a lovelorn prince. Unfolding throughout the city and its restored historic sites, the exhibition comprises some 70 site-specific projects, each conceived through collaborations with local artisans, to explore the movement of food, legacy of the region’s spice trade and dining as a communal and emotional experience. Among these are Slavs and Tatars who pair with local ceramicist Abdullo Narzullaev to present an installation that celebrates the Central Asian melon, and Mexican artist Delcy Morelos who has worked with spice merchant Abdulnabil Kamalov and will show a woven sculpture made from spices, earth, desert sand and clay. There’ll also be a series of culinary events taking place weekly at the biennial’s Café Oshqozon (literally ‘vessel to prepare food’ in Uzbek, aka the stomach). On the opening and closing weekends, for example, the menus will be prepared by chef and Buddhist nun Jeong Kwan, for whom food, as well as nourishing and healing, is a meditative experience. Yuwen Jiang

Eyewitness

Sainsbury Centre, Norwich, 20 September 2025 – 15 February 2026

True crime podcast aficionados, rejoice! The fascination for the morbid is being legitimised by cultural institutions. Art and literary history, after all, provides an undeniable record of humankind’s longstanding craving for macabre storytelling: think gory mythologies, classical tragedy and religious martyrdom. Do such works expunge us of our passions, fuel our thirst for blood or is it all just a byproduct of our inherently violent societies? You can ask the policymakers (still) arguing about violent video games. Or the Sainsbury Centre, that is now packaging the thrill of homicide and cruelty-at-large from your favourite classics into ‘a new exhibition asking why people across the world are so fascinated by the dramatisation of killing’. The exhibition is part of a larger group of shows at the Centre pleadingly titled, Can We Stop Killing Each Other? Expect tholu bommalata shadow puppets from southern India, woodcuts from Edo-period Kabuki theatre, paintings rendering popular British dramas like Macbeth and contemporary video works borrowing from Hollywood film. The bottom line, I guess, is that if there’s one thing that unites humanity, it’s that we’re a nasty bunch. Mia Stern