As cartoons and animated bodies stretch, splat and spin, what contortions of labour are going on behind the scenes?

Animated cartoons are serious tricksters. Not only do they revel in unbounded play and plasmatic possibility, enticing us with fluid acts of transmutation and dazzling metamorphosis, they course with their own dark and deceptive magic while they’re at it, troubling the relation between life and image. I’m not talking about the fundamental spark of animism that enlivens all animation – the irreducible mystery that inspired Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein to gloss so ecstatically on the films of Walt Disney, suggesting that ancient beliefs of a distributed ‘soul’ might reside in the act of bringing drawings ‘to life’ with modern movie cameras – but rather something a little more mundane. A slippery sleight of hand perhaps, or a crude displacement of attention.

While anarchic toons have long waged war for freedom from the tyranny of time and space, reshaping themselves into improbable new forms and punching impressive holes into our fundamental laws of physics, the process of animation itself perpetrates an inverse restraint on the bodies of its animators. Every time Road Runner disappeared into a trompe-l’œil tunnel, Tasmanian Devil evaporated into a scratchy cyclonic gust or Wile E. Coyote rebounded from injury with the immortal elasticity of a bestial Rasputin, you can be sure that something contrastingly static and arduous was happening behind the scenes. For the people hunched over the drawing boards, tirelessly compositing acetates and linking the key frames that bring forth animation’s mesmerising approximation of life, making pictures move has always been a dastardly and tedious procedure, and one often fraught with difficult labour relations.

You’d be surprised to think so while watching Disney’s short documentary 4 Artists Paint 1 Tree, originally aired on US television in 1958. With sorcerous wisdom, Walt introduces his loyal team of animator-apprentices, explaining how their unique styles are merged miraculously in the melting pot of studio cohesion. He’s so keen to prove it, in fact, that he dispatches four of them into the wilderness, tasked with capturing the likeness of a gnarled old oak in styles that range from eldritch expressionism to bombastic vorticist eruption. It’d be a perfectly delightful glimpse into the harmonious environs of Disney’s dream factory if it weren’t for the knowledge that its host was an aggressive union buster and FBI informant, a rabid anticommunist who had keenly reported the indignation of overworked and underpaid animators to the House Un-American Activities Committee during McCarthyism’s Red Scare.

This summer’s biggest animated blockbusters, Sony’s Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse and Paramount’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem, betray just how persistent the turbulent conditions of commercial animation production remain. Both films promised to melt the eyeballs of the entire family with their gorgeous, multilayered and visually complex cartoons. While Spider-Verse’s plurality of worlds required a style so richly textured with lysergic oddness that it risked attaining narcotic status, TMNT’s focus on the tactility of bodily mutation required a joyfully bamboozling technique that left viewers questioning what they were really looking at: thickly daubed 2D crayon renderings or a sculpted reptilian menagerie worthy of Jan Švankmajer’s janky stop-motion weirdness? The human costs of such radical innovations have been widely discussed, with Sony downplaying the demoralising effect of directorial mismanagement that saw animators required to revise or fully scrap intricately rendered scenes, and Paramount approached directly by director Jeff Rowe and writer-producer Seth Rogen to ensure that overwork and burnout weren’t aspects of the filmmaking process for technical staff.

It’s worth asking how these issues scale to the more modest and solitary conditions of art production, a scene in which artist-animators usually work in isolation without the armature of a production studio and creative team. Despite technological advances, intergenerational voices from Lisa Crafts and Sally Cruikshank to Sophie Koko Gate continue to express how painfully involving animation can be, its production placing huge constraints on time and patience in a broader industry metabolised by immediacy and the rapid turnover of content. For Hungarian artist Petra Szemán, a self-proclaimed ‘video gremlin’ whose animated films and videogames poignantly explore the multiplanar transmigration of identity between bodies and screens, it is a practice of mitigating bodily strain with ergonomic ingenuity. “It’s a constant negotiation between my body and the body I’m animating,” they’ve suggested, noting how the use of customised gloves and production tools are necessary supports when meeting the demands of crafting fluidly animated avatars. “My physical body seems to disintegrate the smoother and fuller the animated one gets; pleasing animation and bodily comfort appear to be inversely proportional to one another.”

Perhaps less visible to most of us are the discomforts experienced by the video creators of the digital gig economy who are routinely commissioned by established artists to produce work in game engines and graphics applications such as Unity, Unreal or Autodesk 3Ds Max – the programs delivering that now-ubiquitous, gamelike, cinematic, science-fiction polish. This work carries the desired visual charge of big-budget studio animation, but it often requires its freelance labourers to sacrifice parts of their own budget on outsourced rendering tasks in order to meet tight deadlines and even tighter institutional projection specifications. The units of computational labour purchased in such instances are known, quite macabrely, as ‘render slaves’, and render slaves work – you guessed it – on ‘render farms’. I’m not exactly sure where the ease with which such processes both employ and normalise the language of subjection leaves us, but it demonstrates a dynamic of servitude and hardship that remains integral to the manufacture of the animated image.

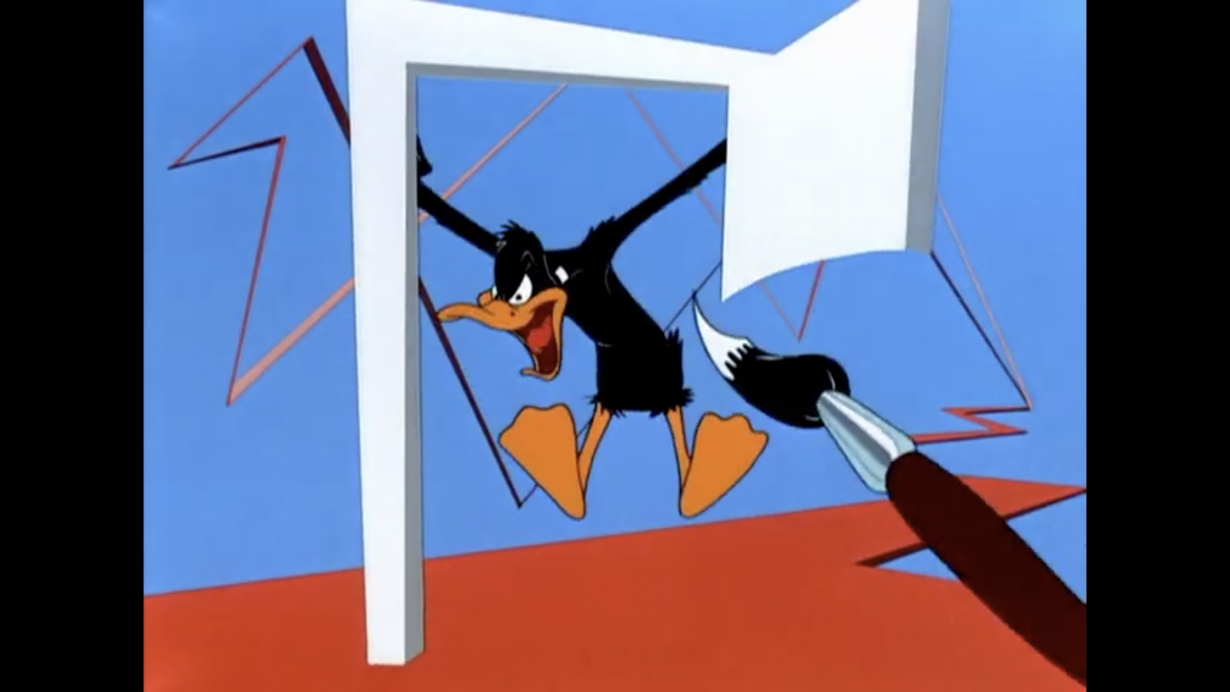

Have animators always been so uneasily tethered to their creations? In legendary 1950s Looney Tunes shorts such as Duck Amuck (1953) and Rabbit Rampage (1955), Chuck Jones would frequently give his unruly characters hell, his paintbrush or draughtsman’s pencil tearing through the fourth-wall into the Technicolor locales of Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, scrambling everything with a playful simulation of industrial sabotage. As animation production evolves, visualising increasingly enchanting and improbable universes, we’d do well to observe the shadow world it leaves in its wake, and hope it’s not one in which animators are pressed into the same impossible contortions as their cartoon offspring.