T. Richard Blurton’s new book ranges from palaeolithic tools through to contemporary works of art

‘Colour is one of the most obvious, insistent and frankly delightful elements of South Asian culture.’ That’s just one of the banal and trivialising comments in this book, in which ‘India’ is actually South Asia – spanning Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. This act of generosity is, on the face of it, laudable: it allows the author to insist on an idea of ‘India’ or South Asia as multilingual, multireligious and home to a variety of cultures, in contradistinction to, say, the recent Hindu-fundamentalist reconstruction of the Indian nation. But the India/South Asia business is not framed as a political statement;

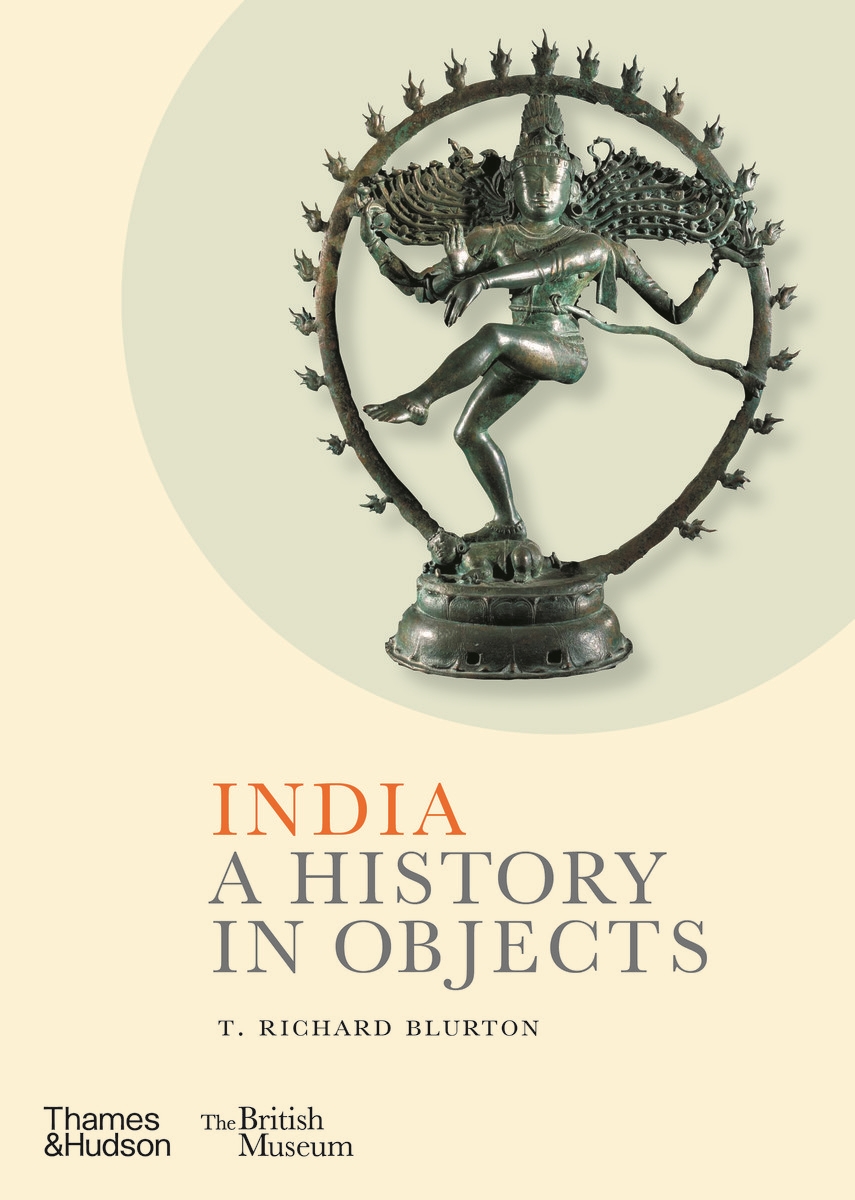

in fact, the book is introduced as not being about South Asians at all. ‘Without understanding cultures other than one’s own, we are reduced. With South Asians – both in Asia and today dispersed on every other continent – making up a fifth of the worlds’ population, it is essential to undertake this task,’ T. Richard Blurton concludes in his introduction, leaving the reader with the lingering thought that this book is for non-South Asians who need to understand South Asians, because sooner or later they’re going to be overrun by them. Unless that intro is simply an advert for the importance and value of Western museums, and their continuing to hold objects that came from someplace else. The objects here ‘come’ from the British Museum.

They span Palaeolithic tools (from about 1 million BCE) through to contemporary works of art by the likes of Bharti Kher. Blurton gallops through that timeframe at breakneck pace, pausing, usefully, to explore the relationship between the urban empires of the plains and the more freewheeling upland areas, as well as evidence for South Asia’s historic cosmopolitanism thanks to its trade networks. And pausing too to explain the key figures who shaped the continent – among them the Buddha, Mahavira, and the Buddhist emperor Ashoka (who ruled from c. 268–232 BCE). But while Blurton points out that Ashoka’s iconography can now be found in the new Indian republic’s iconography (a contemporary banknote is displayed as evidence), he doesn’t really explore the extent to which, until the nineteenth century, it was buried beneath a Hindu ascendency. The focus on what was dug up or unearthed conceals the reasons some of these things remained hidden.

Similarly, many of the objects displayed are accompanied by credits to the Western collectors and archaeologists who either dug them up or donated them to the British Museum: Beatrice de Cardi (an early-twentieth-century archaeologist) Collection; the Bridge family; Sir Harold Arthur Deane, etc. The colonial era, or ‘the British period’, as it is stated here, is downplayed – ‘by the 19th century, painters were demonstrating a mastery of European perspective’, Blurton states, without fully going into the reasons why; a sword looted following the eighteenth-century sack of Tipu Sultan’s capital, Seringapatam, is presented without much discussion of how it ended up in Britain. It comes to a head in the author’s discussion of ‘Company painting’ – works that captured the flora and fauna, peoples and customs of India, by local painters for British clients. But here introduced without a clear link to their relationships to the cataloguing, exploiting and pigeonholing that define the colonial impulse. Perhaps, then, objects alone can only tell us so much.

India: A History in Objects by T. Richard Blurton, Thames & Hudson, £30 (hardcover)