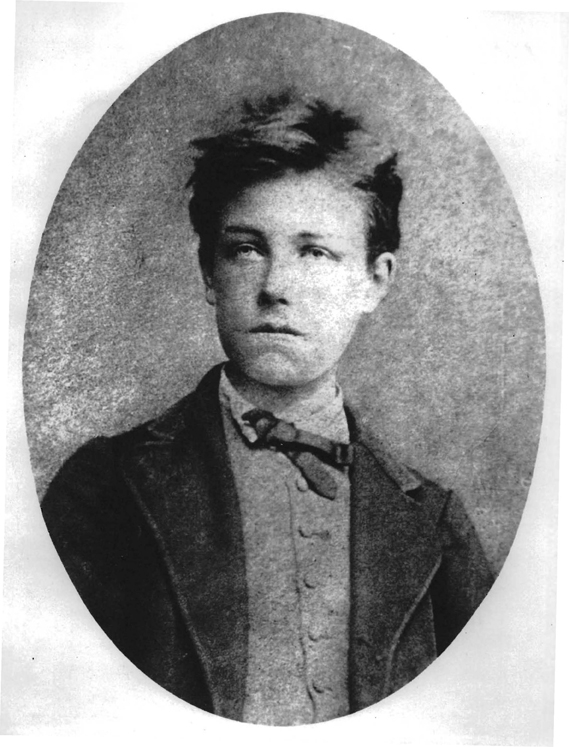

Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud was a French symbolist poet. His work was barely noticed in his own time but profoundly influenced the Surrealists during the 1920s. Because of his reputation for antisocial behaviour, he became an icon of youthful revolt. He was born in Charleville, northern France, in 1854. By the time he was twenty-one, he had stopped writing poetry and spent most of the rest of his life in Africa working as a commercial trader. He died at thirty-seven in Marseilles from cancer.

ARTREVIEW

You made a statement about your work that has gone down in history: ‘I is an other’. What do you think of artist statements today?

Jean Nicolas Arthur RIMBAUD

They are a bureaucratic form relating only to the monetisation and capitalisation of art education.

AR It’s a much more helpful kind of language, though, isn’t it? I make these objects and I have these ideas.

JNAR A feature of it is that objects seem without substance and ideas are interchangeable. An artist says he or she takes a critical view of social, political and cultural issues; they mention an idea that they know will sound important from their experience of the professional sphere in which they seek to advance; it’s for the same reason that they inserted such ideas into their work in the first place. They say things like: I am arranging familiar visual signs into new conceptually layered pieces.

AR Statements by Mondrian or someone are hard to fathom, most people find.

JNAR A statement for Mondrian, as it is for myself, is always a polemic. He writes to a friend in 1943: ‘Only now I become conscious that my work in black, white and little colour planes has been merely drawing in oil colour. In drawing, the lines are the principal means of expression. In painting, however, the lines are absorbed by the colour planes; but the limitations of the planes show themselves as lines and conserve their great value.’ He highlights relationships that are concrete but extremely narrow. The insight itself is narrow; he wants it to be noticed that an apparently confined mere set of visual proposals is actually doing something.

AR Well, OK. On a different track: what’s it like being the model bohemian artist-rebel?

JNAR In some minds I’ll always be the evil, teenage genius and great corruptor.

AR What did you corrupt?

JNAR Poetry; art: the whole thing. You know, Paul Verlaine was a great poet, and his letters to me had memorable lines such as, ‘I am your old cunt ever open’. His wife burnt most of them. She had about 40 and she was going to produce them in court for the divorce she wanted on the grounds of his disgusting relationship with me. But she got the divorce anyway, for his physical cruelty, and didn’t need to show the letters.

AR What do you think about that kind of language now?

JNAR I think it’s fine. I thought Étienne Carjat, who took the famous photo of me age seventeen, was an old cunt too. It’s a different usage, but context is all, it’s obvious what is meant: he was a cunt who took a photo of me that I couldn’t care less about. With Verlaine’s letter to me, the meaning is clear – I can always use him sexually – but also perverse – he’s got an arse, not a cunt. And he also brings in the sense in which I viewed Carjat as nothing but an old cunt, because Verlaine was besotted with me, but he knew I would betray him, the old cunt.

AR You sound absolutely horrible! What did you think of London when you lived there?

JNAR How can I describe the dull daylight of unchanging grey skies, the imperial effect of these buildings, the eternally snow-covered ground? Here, with an odd flair for enormity, are reconstructed all the wooden wonders of classical architecture. I visit exhibitions of paintings in halls 20 times the size of Hampton Court.

AR Ah I see, you’re feeling you’re there right now: what exhibitions in particular did you like?

JNAR In a daze we found ourselves face-to-face, in a show of French art, with Fantin-Latour’s group portrait of poets round a table, including Verlaine and me. Ourselves looking out at us in London: “Fantin forever!” Verlaine yelled, because we were drunk, as we always were.

AR Do you go to shows much today?

A black, E white, I red, O blue, U green: vowels. One day I’ll tell your embryonic births…

JNAR I just saw Jonathan Meese at Modern Art, and then I walked a long way to the Chisenhale Gallery and saw Caragh Thuring. At first I said to myself: these shows are good followed by bad: good fun and energy followed by meek obedience that just makes one glaze over. Then I thought the opposite: the first was tedious in its obvious masculinism and the second good in its visual sophistication and impressively minimalist design. A black, E white, I red, O blue, U green: vowels. One day I’ll tell your embryonic births…

AR Are you hallucinating?

JNAR Painted masks beneath a lantern beaten by cold nights, a stupid water nymph in shrieking garments deep in the riverbed.

AR You wrote most of your poetry in a four-year period starting at the age of sixteen. Where did it come from?

JNAR At first it was a rocking of existing conventions, and then it was something genuinely new, based on exploring subconscious realms, which I did partly by a logical derangement of all the senses, through the use of drugs. I became a seer.

AR How do you mean?

JNAR I got used to hallucinations, pure and simple: I would see, fair and square, a mosque where there was a factory, a drum-core of angels, coaches on the roads in the sky, a drawing room at the bottom of a lake; monsters, mysteries; horrors leapt up before me from the titles of some vaudeville.

AR And that was always the source? Were there any other ways of generating content?

JNAR And then I explained my magic sophisms by turning words into hallucinations!

AR Uh-oh, are you going off on one now?

JNAR The song is very rarely the work of the singer – that is, his thought, sung and understood. For I is an other. If brass wakes as a bugle, it’s not its fault. That is quite clear to me: I am a spectator at the flowering of my thought: I watch it, I listen to it: I draw a bow across a string: a symphony stirs in the depths, or surges onto the stage.

AR What do you think of painting these days?

The song is very rarely the work of the singer – that is, his thought, sung and understood. For I is an other. That is quite clear to me: I am a spectator at the flowering of my thought: I watch it, I listen to it

JNAR I saw The Forever Now exhibition at MoMA. It seemed provincial, and the reviews I read were incapable of seeing any big picture other than mentioning other artists who seem just like the ones who are in the show but lamenting them not being in it. Also a basic premise of the reviews, absorbed from the catalogue essay, that the artists in the show feel at home with painting from the past, seems untenable: from the evidence of the paintings, it’s more that they seem at home with superficial impressions of art of the last few decades only.

AR What’s the difference?

JNAR Painting dealing with light, or indeed with anything in physical reality – for light is only a particularly powerful and immediate way in which the complexity of the totality of physical reality is revealed to us – was foreign to the show. The ‘past’ is not really available to these people as far as is indicated by anything they actually do, only the past from neo-Expressionism onwards. It’s as if they see the whole history of art in terms of Neo-expressionist quotes from it; so they never get beyond manneristic signs. Hardly any reviewer failed to celebrate Rashid Johnson’s referencing of the paintings of Dubuffet. But these politely provocative all-black surfaces, made of soap and wax and titled with the youthful mass-media cliché ‘cosmic slop’ – which had a very different, mind-freeing resonance when George Clinton originated it 40 years ago in the context of funk – really reference the commonest, least interesting or engaging, mere sign of a Dubuffet surface, and maybe a few Fontana surfaces, too. The Johnsons share with everything else in the show the ability to look instantly and simultaneously lovely and completely insulting and sad.

AR In the art community today there’s a feeling that painting is the sell-out medium, and critical art is better. Do you agree?

JNAR Yes. But only if this show is what is meant by ‘painting’. But it is probably more like the kind of painting that sells, so it possesses authority just from being represented a lot in shows and fairs, which makes it likely it will get gathered together in a museum at some point. The artists don’t necessarily elect to be sellable in the way that a critical artist such as that Belgian or Dutch guy who puts on his Enjoy Poverty events in the Congo elects to be critical.

AR Renzo Martens; he’s Dutch but lives in Brussels.

JNAR Yes, it’s not important: him. This is a brilliantly creative and, you could certainly say in conceptual terms, ‘beautiful’ series of artistic actions, endlessly subtle. The painters in The Forever Now by contrast are not at fault for being insufficiently brilliantly critical but for not being of much interest (as yet) as painters. The criticality of painting works in a way that has its own subtlety. Criticality as it is understood in art contexts today is just a mode. Martens’s revelations about all sorts of systems of economy operating in concert are easily found out by other means, by reading books and following what is reported by the mass media. He crystallises such information brilliantly, but only like Monet, in my time, crystallised by visual means information about objects and fleeting light. Monet didn’t discover light. Or even discover that we don’t necessarily see things in reality in the way a basically Renaissance visual structure suggests. He did something in painting that effectively was a response to new ways of seeing that were already in place, and if anything, they were in place because of how ‘seeing’ works in a shared ‘visual imaginary’ (as Rancière would call it, referring to the always altering interactions of politics, society and culture), not because of how painting works.

AR What about Martens again?

JNAR Ultimately Martens isn’t much use on the high-moral-ground terms on which critical art is purported to operate, and that’s because this ground is fictional. In economic terms critical art needs something to compensate for its lack of immediate attractiveness so the myth of actually being effective as revolt is encouraged in the selling of that art. Martens is an artist developing certain themes from the Hans Haacke days, coming up with superb refinements on the concept of complicity. The element of the superb is real. The problem of the painters in The Forever Now is how lost they are in relation to equivalent concepts in their own fields. But if they were more acute, it wouldn’t make them less sellable or more sellable. ‘Art’ has its own peculiar structures that must be respected, as Marx and Engels often stated: these great fellows from my own time; like Monet. In any case, it’s only later Marxists who went a bit mad, such as Lukács, who insisted that art only has value if it directly addresses by conventional means the issue of emancipation.

AR People today love Laura Owens’s paintings because they’re very free about modernist rules. She can paint a flower if she wants, or just brushstrokes.

JNAR The largely abstract paintings in The Forever Now, whether they had free-floating signs of flowers, or perhaps seemed to be bubbling pools of black mud, or were reduced merely to the sign for a man that a child might draw, were not beautiful or effective or successful or meaningful because of how much a flower was evoked, or a mud pool seemed to be right there, or innocence was evoked. If the paintings release us from habits of seeing, or make the world as a totality newly vivid to us – which unfortunately they didn’t much in this show, but if they did – then that emancipatory content would be, effectively, critical. We would be empowered by it, because we’d be temporarily enabled to see ourselves: to see life. But it would happen because the works, in their own language, did something new, that we didn’t already know about, and did it efficiently.

This article was first published in the January & February 2015 issue.