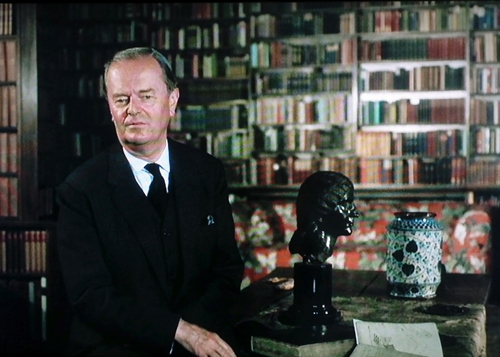

The art historian, author and popular television broadcaster Sir Kenneth Clark, was born in 1903. He was the youngest-ever director of London’s National Gallery, taking up the position in 1933 at the age of thirty. In 1969 he wrote and presented the tv series Civilisation, which described the history of Western civilisation through its surviving monuments of art. He received many decorations, including a life peerage. He died in 1983.

ARTREVIEW

TV’s very different since you made Civilisation. In fact anyone can make films now and they don’t even have to be on tv. Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore is considered a great inspiration to the YouTube generation.

Sir Kenneth Clark

Compared to today’s typical documentary films on mainstream TV about art and culture, that video is a relief. No motiveless laughter merely to put the audience at ease or presenters repeatedly exclaiming the word ‘extraordinary’ in front of an artwork instead of working out a point to make about it.

AR What did you like positively about Leckey’s film, though, on its own terms?

SKC Well, I wouldn’t go that far. Anyone who’s been in a TV edit suite knows that if you put images with sounds that don’t fit, it can create an eerie effect. I think his film is beneficial for artworld professionals. They like to feel there’s something important that they’ve discovered. We’ve all got to feel good about ourselves, however fatuous the reasons we come up with. Leckey provides a service, supplying delusional importance to a system that needs to keep pumping out exactly that product to a public happy to swallow it.

AR Was it hard work making Civilisation?

SKC Not really. I thought out the themes and then we went and did the work. I read my material from an autocue. When I was first making notes for the series, I assumed it would be lectures from a studio with slides. But the director gradually got the idea we should go round the world for two years and film things for real. Between us we invented by accident the authored TV documentary. It was enjoyable to make, and then it was surprisingly successful. It kept being shown at the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, DC, at lunchtime screenings for 300 people; on the first day 24,000 showed up, including Jackie Onassis and half of President Nixon’s cabinet. I went to an event to honour me there, and the mass hysteria was disturbing. I had to go in the toilet and have a weep at one point. I was primitively howling for 15 minutes.

AR Why?

SKC Confusion at the adulation: it was like there was a plague and they thought I was the doctor. I suppose the success of the series in the States was due to the reassurance it gave to bourgeois values. On the other hand it was just as successful in Poland and Romania, which in those days were socialist countries.

AR You were in your late sixties by then. Did you think the world was about to be overrun by socialism and it was important to round up all the beautiful cultural treasures for one last sigh of reverence before they were swept away by barbarians?

SKC Yes, something like that. I was always worried about things breaking down.

AR What’s the best fun you ever had at an art exhibition?

SKC Oh without doubt soaking up the Bellini show in Venice in 1949. I really thought I was in the company of a dear friend. I went again and again, day after day for three weeks. At every point he restored my faith in mankind. Almost alone among the greats he is optimistic. He knew tragedy in his youth, of course. But in middle age he came to look for those things in life that are calm and life-giving. Men, landscapes, buildings, all take on this feeling of natural goodness. When I was coming from the hotel one day on the way to visit the Bellini show, I could see through the doors of a private gallery, on the corner of the piazza where I was staying, and I made out large canvases in there covered in scrawls of paint. No greater contrast to the comfort of Bellini could be imagined. They screamed from the back of a banal modern interior. But in the end I went in, and recognised it as the work of a genuine artist. The rhythms, the control, the surprise and the unity – it was overwhelming. At first I’d been horrified; now I felt a genuine connection to the experience I’d been having every day with Bellini, and was about to have again in a minute. It was the first European exhibition of Jackson Pollock.

AR What happens with an autocue?

SKC You write something and the words get transferred onto a contraption by a technician, and then you read them as you’re being filmed, in a location.

AR How do you get it to sound like you’re not reading?

SKC Well, it’s a knack: you just have it. I’d been lecturing for 40 years. You usually have to repeat it a few times, so the crew and the director can arrange the camera moves. You rediscover the spontaneity that was there when you wrote the material in the first place, which, again, is a matter of rhythm. You’ve done it yourself, haven’t you?

Gentile Bellini, Procession in St Mark’s Square, 1496, tempera and oil on canvas, 367 × 745 cm

AR Very little, and not at all on any of my own programmes; occasionally if I presented live from a TV studio. I found it constraining. When you wrote a book about Piero della Francesca in 1951 was it hard to think of things to say?

SKC No, there wasn’t anything else on him at the time except a brilliant but in some ways obscure work by Roberto Longhi from 1927. For me it’s Piero’s quietness that compels. In the hands of one who uses it creatively, the word ‘colour’ means almost the reverse of its connotation in popular speech. There it means number, variety and contrast. But colour used to reshape the world as part of a consistent philosophy must be restricted to those colours that are on easy terms with one another. Shouting will get them nowhere. It is only in quiet discourse together that a new truth may emerge. La vérité est dans une nuance. The relationship of colours in Piero corresponds to a similar relationship of forms. The impact on one another of his slatey blue and ochre, or porphyry and serpentine, has the same degree of resonance as the impact of the arcs, spheres and cylinders that constitute his form world. Both are muted without being deadened. Anyway, to get the work done I drove around in Florence to the Piero sites, which I’d known intimately for years. The boss of Phaidon had some scaffolding put up in the cathedral at Arezzo, so photos could be taken of the frescoes. I sat in a café every evening starting at 4.30pm, overlooking the bustling Piazza di S Francesco, and wrote my notes. On other days I was in the café on the square in Sansepolcro, which was much quieter, because no one ever visited that town then. I stayed at Bernard Berenson’s place. The Phaidon boss had never heard of him. In fact he hadn’t heard of Piero when I initially proposed writing the book. I introduced him to Berenson. I told him Berenson’s best works were the collected four prefaces to his lists of authentic paintings. It turned out this had only sold a few copies, as it looked a bit boring the way it was designed and laid out. So the Phaidon boss made an agreement with Berenson and reissued it with an attractive redesign and it immediately sold 60,000 copies. You had a bit of success like that with This Is Modern Art, didn’t you, Matthew?

AR Yes. But I don’t think the reason was the layout. Rather, it was assumed to be a book that forgave ordinary people for being naive. As art was just beginning to become a consumer product during the 1990s, something to be enjoyed as entertainment, readers were grateful for what they thought of as a guide to how to do it. When you watch tv documentaries on art today, what do you get from them?

SKC Generalised enthusiasm with a few historical markers of a very simplified kind.

AR Do you think art is explained helpfully to a wide audience on these programmes?

SKC It depends what you mean by helpful. The audience has been conditioned by the cultural dumbing-down process, which was itself the result of marketing requirements, to think of art as a certain thing. Civilisation was frequently marred by windbaggery. Nevertheless I occasionally gave the impression during the series that I thought of paintings and sculptures as having been consciously structured, the result of a series of conceptual and visual decisions. This is now unknown on TV. You’re supposed to talk about art as if it’s a branch of fantasy, not a class of objects. I’m planning not to be in the vicinity of a TV during the run of the planned remake of Civilisation. Communicating to a mass audience about culture no longer involves getting ideas across that you’ve had yourself about a particular subject. A massive machine of producer interference ensures that all ideas that eventually make it into the programme support a primary and overriding single corporate aim of unctuously sucking up to an imagined audience that furiously rejects all knowledge unless it already more or less possesses it. That’s why TV programmes about art are a form now pervaded almost entirely by clich.s. There are exceptions: Jonathan Meades’s reflections on architecture, for example. But if you get involved in mass-audience communication about culture, and you have anything peculiar to say – peculiar in the new mass-audience placatory terms I just outlined – it’s a very neurotic and awkward struggle. And the presenters on these programmes at the moment rarely show any evidence of wanting to engage in it.

AR In the artworld in the States now, everyone’s going on about the art market bubble and flipping. What do you think of all that?

SKC Marketing in itself is not necessarily a problem. But it can get out of hand. One disturbing result when commercialism overwhelms all other considerations has already been mentioned, the crushing of intellectual content on TV. Another one, not unrelated, is that the utterances of art advisers and dealers – who, after all, are only snake-oil salesmen – enjoy the status, on social media and in online art publications, of actual thought. There are many different levels of criticism and analysis today, and much genuinely insightful work by experts goes on with some of it making its way into art books for the general public and articles in art magazines, but still that is for a relative minority. It’s unfortunate that the stuff that is most widely consumed is by depraved sickos calling themselves advisers, and so on, whose only motivation is profit. These conmen paint a distorted picture of those who hire their services as healthily adjusted types: they say their clients’ motivation in art speculation is never profit alone. Rather, there is the faint and barely consciously registered awareness of a future possible profit, but this is far outweighed by a sheer love and passion for art. Now, if you gently mention there might be something self-serving about this characterisation both of the client and by inference the noble adviser, they reply that you are a kneejerk whiner and a h8-er and de-friend you.

This article was first published in the May 2015 issue.