Martínez began as head of Basel’s University of Applied Sciences and Arts art department in 2014; she promptly renamed it the Institut Kunst Gender Natur. Here, she speaks about what’s in a name, and the importance of intensity, friendship and providing hybrid models for students

ArtReview: Tell me the thinking behind the naming of the Institut Kunst Gender Natur (Institute Art Gender Nature) HGK FHNW.

Chus Martínez: When I first arrived at the institute, the new campus was about to open. I thought we needed to decide what substances are really transformative to life. I consider art, normally perceived as the production of an experience, as being one such transformative ‘substance’. Within that, I thought we had a chance here to entangle the transformative power of gender and of nature.

I thought we should create an environment where we put this entanglement at its centre. That doesn’t mean that if you’re a painter dealing with formal questions you must now deal with nature, or with gender; it just reflects that, in 2023, the frame in which your formalism takes place is already within this transformative axis, and that you need to understand what it means to participate in it, even if it is to then ignore it. Because there is no way around it.

AR: What does that look like in practice?

CM: We started to include science in this discussion. Can we have a nature-oriented technology? Can we have a nonwhite technology? Is it desirable? Yes. Then one day the campus took another form, where all the design schools or design institutes entered a more, let’s say, conglomerate arrangement, and they needed a different description. The director of the campus suggested putting this curricular process into the name of the school, making it the headline. There were some who argued that to do so would relativise the importance of art. But being next to nature and gender is a fantastic honour, I think. If we really want to be one of the only art schools with these ideas at its core, why not announce it? For us, it’s fundamental not to situate art outside those considerations, whatever form the art takes.

AR: Since giving the institute its new name, have you seen a shift in the people applying?

CM: Many people immediately said, ‘Well, this is only going to attract those really interested in these subjects’, but it didn’t turn out to be true. People who hadn’t related to these issues before found a way of relating to them. Also, to say it again, we are not a nature-studies discipline, and we are not gender studies. We’re not about cultural studies. We practise art. The way that we understand those questions, notions and debates is still practice-based.

Many practitioners are intrigued by it. We have students who apply saying, ‘I was never concerned about questions of gender, but I’m a male painter and I probably should be, I just don’t know how’. They recognise that you cannot avoid these concepts, and we need to accept that. We have less resistance in our groups, but we see resistance growing in wider society. We still frame many social problems in terms of labour rights. In moments of extreme precarity, people can get super-defensive, and they close down to certain transformations they don’t think are primal to their survival.

AR: You mention questions of economy. How does the city or environment of Basel, which is very beautiful and quite close to nature, but also very expensive, affect the teaching?

CM: While it is culturally conservative, it’s a left-oriented city with a strong Green Party. It’s very invested in the arts and has many different structural examples for the students, from the Kunstmuseum and Kunsthalle, to artist-run spaces that are numerous and varied in nature. It’s a great environment for understanding the systems inside the art system. While the Art Basel art fair is located here, the city has very few commercial galleries. In Zürich there are a few more, but the country as a whole is not flooded with galleries. Many artists here, even very well known ones, don’t have a gallery. There is also a large quantity of subsidised studio space provided by the city. I think students, if we guide them well, will see many different models of being an artist that are not entirely dependent on commercial galleries. That there are many hybrids in between. The city provides those case studies.

AR: How do the bachelor course and the master’s programme differ in teaching?

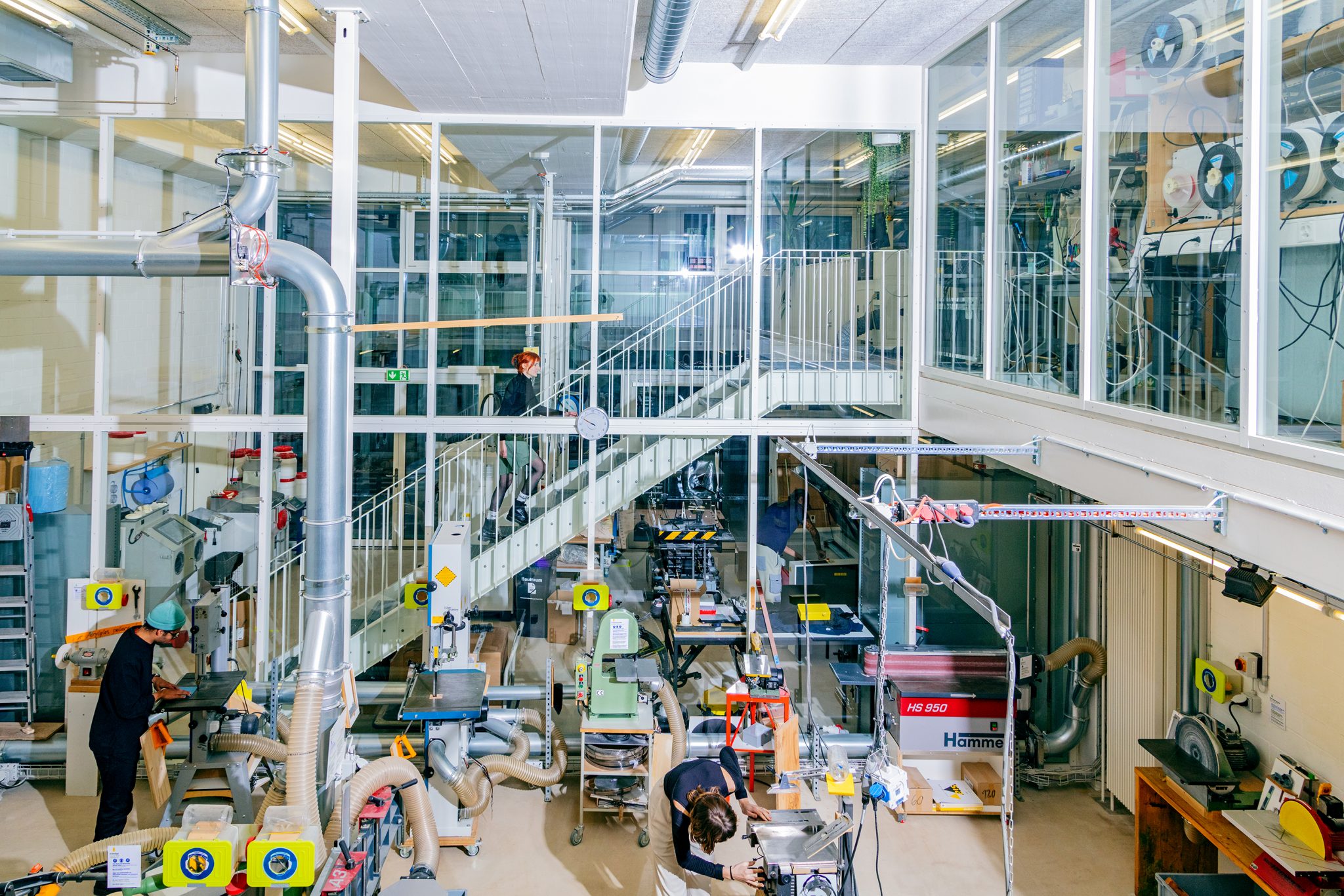

CM: We are a public school, and in the Swiss system we’re not allowed to have thousands of students. We have only 110 students and around 60 teachers. It means that the environment and the closeness are radical. There are enough of us to take care of you. Classroom teaching is performed by three people at the same time. How these three people work together is varied, dynamic and negotiable. Apart from that, we have immense hours of mentoring. I am a former music student, and as a music student you know that you need to practise every day, but you don’t do it. Then you have the teacher on Friday who tells you how bad this is. I’ve been creating a system of mentoring that is similarly dense. It means that you see a lot of people for one-to-one conversations many times. It provides another field in which to negotiate the big questions we’ve spoken about, where you discuss what you have been reading, listening to, working on, cooking. Then there are thousands of micro-personal and micro-collective levels where these questions are renegotiated, reactivated, reinvented, reimagined all the time.

The master’s is a little bit different, but the system is the same. In the MA there is a plenum, which is usually conducted by one teacher, but sometimes more. In the Swiss system, which I think is fantastic, the transfer of knowledge is never just from the individual to collective, but collective to collective. There is collective teaching that’ll collectively transfer to another collective, which is the classroom. It differs from that kind of more German masterclass where a prominent artist transfers onto the group. The Swiss don’t value extraordinary personalities per se. The school is very much designed against that.

AR: What did you study at the conservatoire?

CM: Premodern singing, early music. You were with other people all the time, you needed to listen to others, to synchronise, to adapt. It was a great training. I wanted to bring that to Basel.

AR: What’s the rough international makeup of the students?

CM: In the bachelor programme we have 60 students, and until now they have been mostly Swiss, because it’s a German-language course. It has been changing though: in 2018, after an organisational shift at Corriente Alterna, which began in 1992 as an alternative free school in Lima and was moving to a more commercial model, some Peruvian students asked us for shelter and to be able to finish their degree here. The existing students on the bachelor programme collectively agreed to switch to English to accommodate them. Since the Ukraine crisis began, we have six Ukrainian students in our bachelor programme. The MA, on the contrary, is only in English and is around 60 percent international students and 40 percent Swiss or Swiss-documented students with different backgrounds.

AR: You are known as a curator. How does that affect your teaching?

CM: I don’t consider myself a teacher. I am designing the school, together with my team, very much like a curator. It gives me an incredible opportunity to produce art, but also produce a large conversation. In a certain way it’s much more rewarding, egoistically speaking. For example, if you are producing public programmes in another kind of institution, your audience is far away, you need marketing to fetch them. Here the community is right there. It’s intense, and I like that intensity a lot.

It’s the same with the exhibitions we do at der TANK, a small exhibition space on campus. It’s fed by three types of exhibition. One is commissions. I’m taking care of those, and they are with artists who are dealing with questions of nature. We’ve invited the likes of Eduardo Navarro, Ingela Ihrman, Cecilia Bengolea, Julieta Aranda. We just published a book about all these commissions. Second is a strand in which we revisit work by former students and teachers from the institution, like Sergio Rojas Chaves and Renee Levi, people who many of the present students didn’t even know were connected to us. Then third are the exhibitions self-initiated by students. It’s a super dynamic mini-institution.

AR: How did the pandemic affect the school, has it lefta legacy?

CM: I can only say that during the pandemic I became the Spanish grandmother I am. I decided that we were going to take care of everyone here. We divided ourselves into groups, and I assigned teachers to students so that they were checked in with on a weekly basis. I was offering cooking courses. We were meeting online too, for dance discos and reading groups. It was like Spanish village life: ‘Did you eat well?’ ‘What are you having?’ ‘Do you know how to cook?’ ‘Are you taking care?’ ‘Do you know that actually eating pasta every day is very bad?’ Everyone played that game; nobody left the programme.

For graduation we staged the only physical exhibition by a Swiss school at that time, in Kunsthalle Basel. I said, ‘You are all afraid, but if we are afraid together, it’s better to exhibit the work than skip graduation. Let’s graduate.’ I’m very old-fashioned. I don’t think that we can really be an art school and not care about each other in a holistic way. I need to know if you’re having a good time. Joy and, let’s say, friendship are very important, and I think I’m very upfront about it. Friendship is probably the most important thing in life. An art school is not only teaching you skills, but also giving you peers who, along with the teachers, will be friends and a community for life.

Chus Martínez is director of the Institut Kunst Gender Natur HGK FHNW, Basel