Meetings, non-meetings, Partition plans and the stories in between

To say that Indian writer, journalist and activist Mahasweta Devi (1926–2016) was prolific is an understatement. During the course of her career she wrote over 100 novels (in Bengali). Plus more than 20 collections of short stories. Plus, of course, the journalism and the activism on the side. But nevertheless to the fore. ‘I think a creative writer should have a social conscience,’ she once said, when asked about her involvement in these various spheres of activity that others tend to view as discrete. And why did she do it all? What she did, she said, was the result of repeatedly asking herself a single question: ‘have I done what I could have done?’

It’s unclear as to whether or not Mahasweta’s motivational mantra was founded on the answer to that last question being a satisfied ‘yes’ or a motivating ‘no’: whether, if you like, the whole questioning and self analysis business represents the deployment of the carrot or the stick. Most likely it’s both. All Mahasweta says is that the journalism helped the activism (which focused on social justice in general and the rights of India’s tribal peoples in particular) because government officials were so terrified about what she might write next. And more pointedly, they were terrified about the possibility that whatever it was she might write about would feature themselves in some sort of negative light.

So presumably the whole self-questioning business is Mahasweta saying that she held herself to account in precisely the same way that she held others up to scrutiny. A restating of her belief in equality. Although that still doesn’t move us completely beyond her categorisation of journalism as a form of terrorism. To understand how this might play out, it’s perhaps helpful to look to the words of a prominent Indian writer and activist of a younger generation, Arundhati Roy (here speaking to the closing rally of the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 2003): ‘Our strategy should be not only to confront empire [which in this context we can take to mean oppressive forces in general], but to lay siege to it. To deprive it of oxygen. To shame it. To mock it. With our art, our music, our literature, our stubbornness, our joy, our brilliance, our sheer relentlessness – and our ability to tell our own stories. Stories that are different from the ones we’re being brainwashed to believe.’ To resist universalising narratives and insist on the right of individuals to tell their own stories. ‘I have always said that real history is made by ordinary people,’ Mahasweta once asserted.

Hilariously, given her own hyperproductivity, one of the better-known anecdotes about Mahasweta concerns her having asked, when she was a young girl, the most celebrated of all Bengali writers, Rabindranath Tagore (in whose school she studied), not to write so many books; she didn’t feel she would ever have the time to read them all. But perhaps that’s simply another way in which writing, or art, can be used to exert pressure, to lay siege.

Mahasweta’s short story ‘Pterodactyl, Puran Sahay, and Pirtha’ (1989) introduces ‘in abstract’, as she puts it, ‘my entire tribal experience’: a summary of her core engagement with the plight of India’s Adivasi, or tribal peoples. In it she inscribes the mechanisms that maintain the institutionalised oppression, exploitation and general degeneration of Adivasi (here centred around a fictional tribe, with fictional customs, located in the fictional village of Pirtha, all of it synthesised from Mahasweta’s actual experiences among various tribal peoples). And the ways in which the Adivasi have been written out of the map of the new(ish) nation of India (their lands appropriated, their languages ignored and their traditions and customs written off as premodern superstition). An India founded on narratives of freedom, postcolonial progress and a united nation-state. While deploring the fact that, as a result of all this, most Indians remain unaware of the tribal plight (one of Mahasweta’s missions was to make them aware of it), ‘Pterodactyl…’ also speaks to the difficulties, if not impossibilities, facing outsiders who seek accurately to represent or translate the cultural histories of those people without being caught up, consciously or unconsciously, in the endless cycle of exploitation that has put the Adivasi in this position in the first place. On the one hand she’s describing a kind of Gordian knot in which she wishes to protect a certain kind of cultural relativism, but equally wants to be able to communicate stories on a global level. On the other hand, it’s an argument for why fiction – or the distance from a particular reality that fiction allows – is sometimes needed to support journalism and activism. Even while conceding that this distance is in some ways problematic: that you are, in this instance, taking someone else’s stories and rendering them in your words. Or in words that are more efficient in speaking truth to power. Which leaves you implicated in that power structure itself (a position that the translation to English doubles down on).

To demonstrate this, there’s a passage in the middle of the story in which the author asserts that the more a decolonised and neoliberal India legislates in terms of ‘Constitution and Proclamation’ against the impoverishment and disenfranchisement of tribal peoples – in effect erasing their plight by law if not by action (it’s illegal, so it doesn’t exist) – the more their actual ongoing poverty, and any protest against it, ends up being the preserve of ‘art films’. The generally accepted realm of things that don’t ‘really’ exist. Films that inevitably serve the consciences of the people watching them more than they do the people in them (‘They [the tribal peoples] serve the upper echelons of society in glossy magazines,’ Mahasweta writes). ‘We are hungry, naked poor,’ says one of the tribal inhabitants of Pritha. ‘That will be known on the filims. But filim won’t say who made us hungry, naked, and poor. We don’t beg, don’t want to beg, will people understand this from those pictures?’ And in her highlighting of the difficulty the tribal person has in pronouncing the very word ‘film’, Mahasweta (and her translator) highlights the distance the medium has from this reality.

The passage about art films came to mind during March Meeting 2022, in Sharjah, titled ‘The Afterlives of the Postcolonial’. Not least because Mahasweta’s best-known translator (of ‘Pterodactyl…’, among other works), Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, was giving the keynote address. And because there were plenty of art films or discussion about them on view. And because many of the conflicts highlighted in ‘Pterodactyl…’ underlay much of the debate.

The meeting itself was staged as an encounter between the academic and the artistic. Spivak, whose own academic achievements include foundational work in deconstruction (she translated French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s key deconstructivist text De la grammatologie, 1967, into English) and subaltern studies (her seminal essay on the subject ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ was published in 1985), began by pulling the postcolonial apart, pointing out that the inequities of the caste system had existed in her native India long before any of the class systems imported by colonial powers, and that the construction of postcolonial nation-states contains just as much erasure as any colonisation (people at the top benefit, for people at the bottom nothing changes – “just dates and names”), and suggesting that at times for such nation-states the idea of the postcolonial becomes a cover for an exercise in blaming someone else for your own failings. And with that opened the door to a wider discussion about how any consideration of the postcolonial should also be a consideration of one’s own complicities or entanglements. Before moving on to state that, in an echo of Mahasweta’s dictums, any form of activism needs to be linked to lived experience, and every action needs to be connected to the pursuit of genuine social justice. Most indigenous languages, she pointed out, have no words for concepts like ‘colonialism’ or ‘deconstruction’. Which you might further interpret as a call for less theory and more practice. In connection with which Spivak frequently referenced her own work over the past three decades in the education of landless rural illiterates (adults and children) of West Bengal. Ironically, the theory-to-practice bit is more easily said than done. It loomed over the rest of the conference, in which theoreticians and practitioners (for the main, artists) struggled to connect, to find a common language.

Of course, that last sentence is something of a crude summary of an event at which artists such as Hrair Sarkissian and Carolina Caycedo presented compelling case studies of how to use art to take particular stories to a general audience, while Khalil Rabah did the same in the case of how the silenced can speak. And in which academics like Angela Davis highlighted the ways in which solidarities and sympathies can be found across apparently discrete struggles, in part within the framework of intersectionality (an analytical framework that examines how the complex of factors that make up social and political identity shape relative social discrimination and privilege). It’s a theme that was at once picked up and denied by Dalit scholar Suraj Yengde in a pithy yet moving analysis of India’s caste system, which included musings on whether or not Dalits had art (in the understanding ‘art’ people have of it). While the knowledge and ownership of history, and the problematics of restitution remained equally persistent themes.

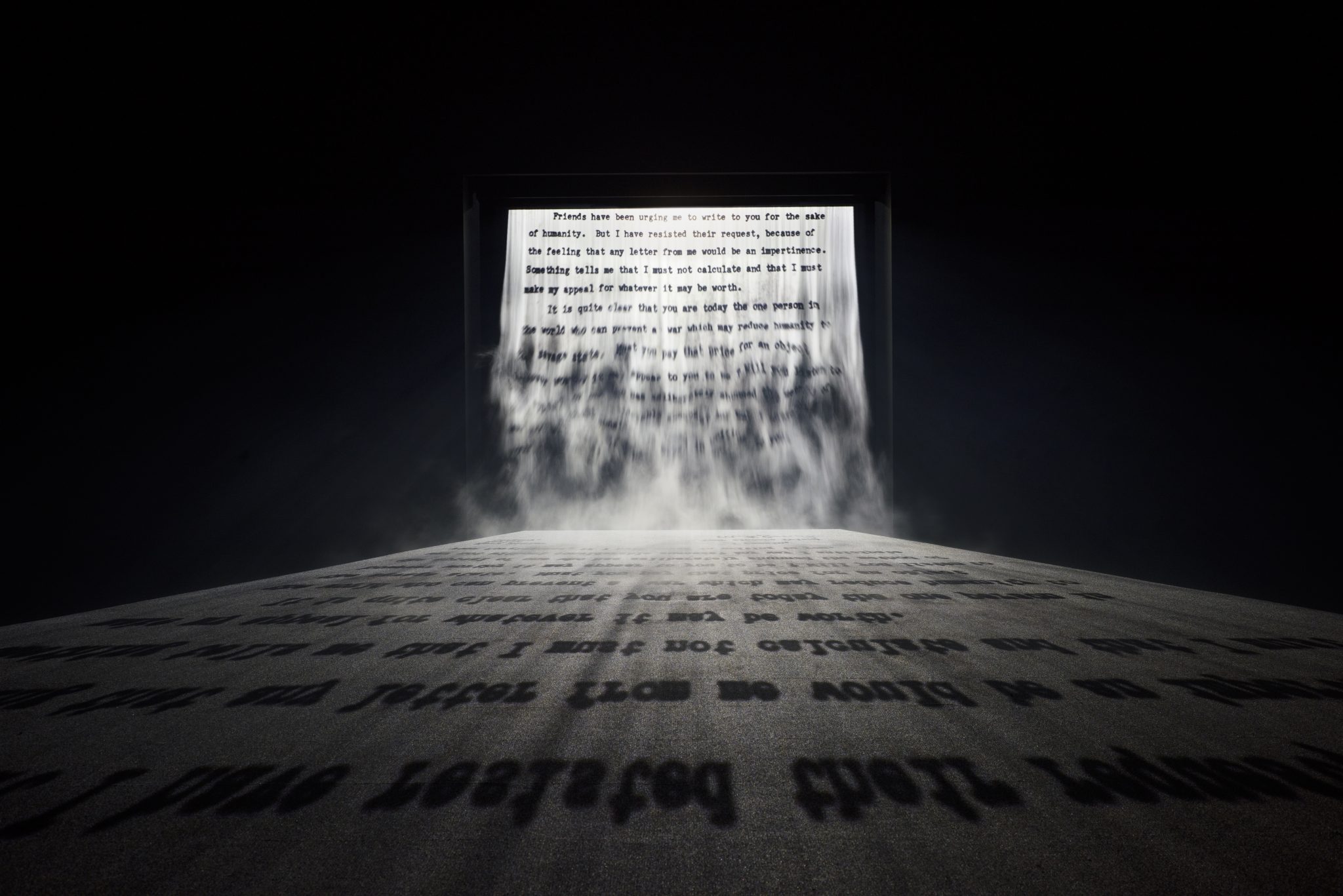

Some months later, the themes of visibility and invisibility, silence, the right to speak and stories not told turned out also to inform an exhibition curated by the Indian artist Jitish Kallat, titled Tangled Hierarchy and currently on show at the John Hansard Gallery, in Southampton, England. It’s staged to coincide with the 75th anniversary (this August) of one of the most traumatic moments in the history of the subcontinent, the partition of British India (in 1947) and the resultant creation of two independent states: India and Pakistan. A moment that led to multiple bloodbaths, a refugee crisis that left an estimated ten to twenty million people displaced and anywhere between two hundred thousand and two million people dead, and laid the seeds for the equation of religion to nationhood that continues to destabilise both nations to this day. And wrote parts of a country out of the map.

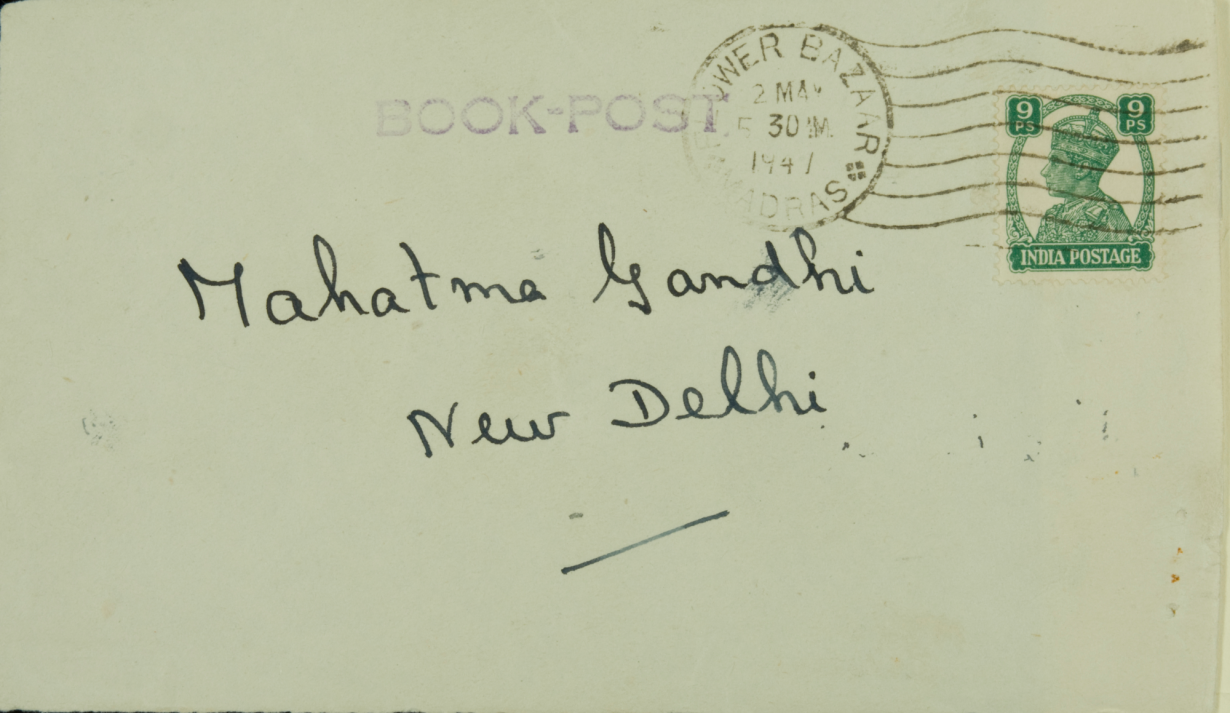

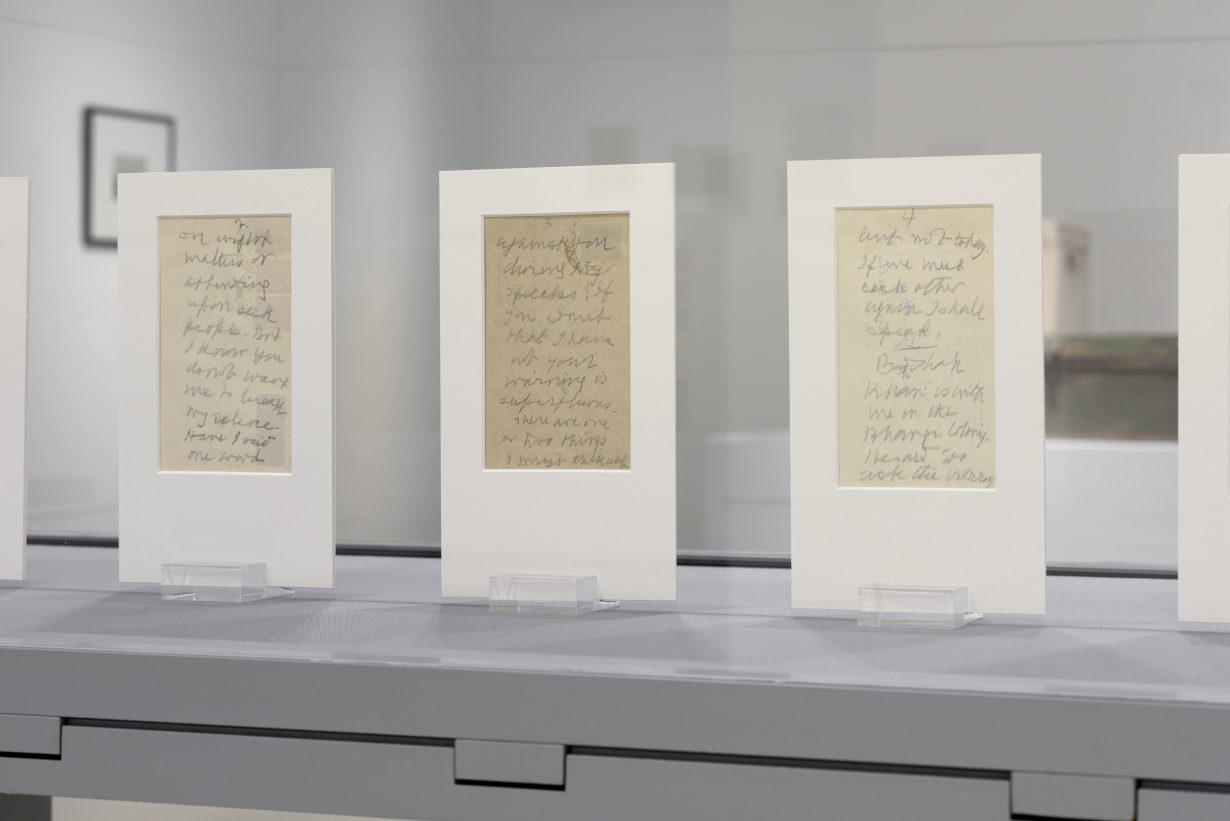

The exhibition revolves around five envelopes addressed to Mahatma Gandhi, on the back of which the ‘father’ of India had written notes to Louis Mountbatten (the last viceroy of India) at a meeting to discuss the immanent partition process. Gandhi himself couldn’t speak at the meeting, which took place on a Monday – 2 June 1947, the day before the Partition plan was formally made public – on account of his having undertaken a vow of silence on Mondays. Gandhi’s hasty-looking scribbles run horizontally across the series of five numbered envelopes (rather than continuing from one to the next), giving what Kallat terms, when we talk about the show, a mixture of casualness and deliberateness (‘a thoughtless word hardly ever escaped my tongue or pen’, Gandhi once boasted, while describing how silence helped him restrain and percolate his thoughts, getting him closer to their truths). The letters, in short, are small, seemingly trivial objects that nevertheless carry a great deal of weight.

‘I’m sorry I can’t speak,’ writes Gandhi. ‘When I took the decision about this Monday silence I did reserve two exceptions, ie. About speaking to high functionaries on urgent matters or attending to sick people. But I know you don’t want to break my silence… there are two things we must talk about, but not today. If we meet each other again I shall speak.’ Although the message appears straightforward you’re nevertheless wondering what Gandhi was really saying: that Partition (to which he was opposed) was unspeakable, Mountbatten was not a high functionary as far as Gandhi was concerned, the matter at hand was not urgent, his lack of speech was a reflection of the fact that Indians were not able to speak meaningfully on the subject of Partition or that he was humiliating his adversary with a display of his own humility (as he often did). Or more simply, that he underestimated the damage that Partition would cause. And why did Gandhi think that Mountbatten did not want him to break his silence? Out of respect for the former’s beliefs? Or because the Englishman was outlining the Partition plan and, knowing Gandhi’s opposition to it, he had decided in any case that there was nothing useful that Gandhi could say about it? We’ll certainly never know: Gandhi’s notes are the only record of the conversation that day. But given all that was to come in the wake of the Mountbatten-Gandhi meeting, there’s a part of you that’s left wondering (to paraphrase Mahasweta), did he do all that he could have done?

Mounted upright, in a glass cabinet, in the middle of the gallery, the five yellowed envelopes seem like the relics of an unknowable piece of performance art. Or the five fingers of a dead man’s hand. Where the gaps between the fingers are the space in which stories are generated.

This reading of the letters is, rather improbably at first, given further force by the neighbouring display of sporting spectacle. Paul Pfeiffer’s Caryatid (2008) is a three-channel looped video showing various footballers diving and writhing from the effects of tackles, which are themselves rendered invisible given that the artist has edited all the other players out of the shot. We don’t know if they are diving or genuinely fouled, acting theatrically or actually in pain. All of which speaks to a photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Games in a refugee camp at Kurkukshetra, Punjab, India (1947), located in the neighbouring gallery. In it, the refugees, a tangled, seemingly joyful mass of raised arms and flying limbs in which the object of the game is unclear and seems unrelated to their recently acquired status as refugees. A mirror of the tumult engulfing their country, perhaps, but not an image of the tumult itself. An echo perhaps of Mahasweta’s words: ‘filim won’t say who made us hungry, naked, and poor. We don’t beg, don’t want to beg, will people understand this from those pictures?’ Capturing the ‘real’ effects of Partition is left to two luggage trunks placed in front of it. Borrowed from the Partition Museum in Amritsar. Evidence as much as exhibit. But, on their own, just as mute as Cartier-Bresson’s photographs. Or Gandhi’s silence.

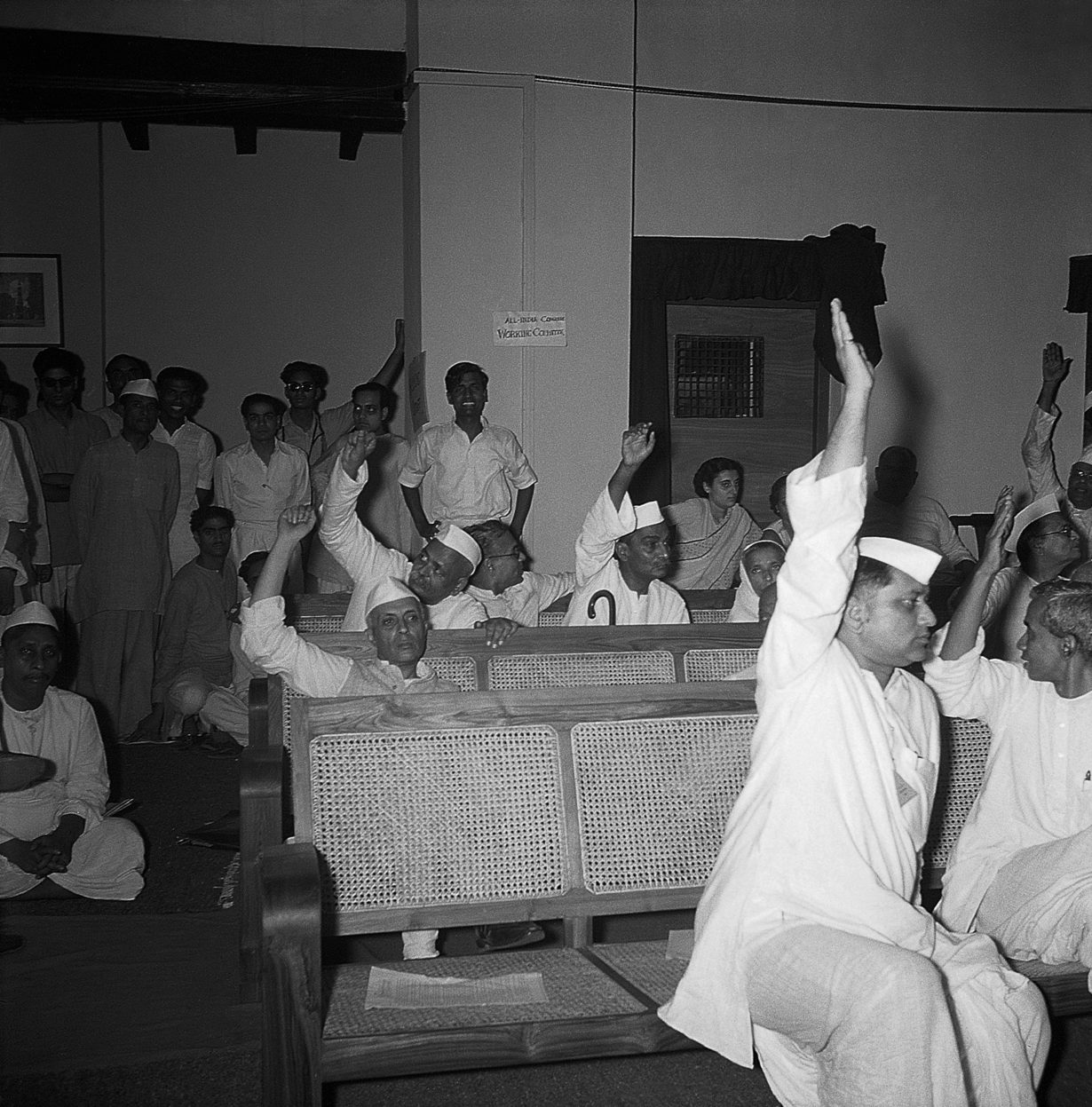

It’s hands aloft again in an archival photograph, taken by Homai Vyarawalla, of the All India Congress Committee meeting on 14 June 1947, at which a show of hands marks the party’s ratification of the Partition plan. India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, slumped on a rather empty bench centre-stage, and Indira Gandhi (Nehru’s daughter), who would later become the country’s first female prime minister, crouched in the background. Which in turn marked Congress’s split with Gandhi. Which in turn leads you back to those empty spaces on Nehru’s bench.

In a touch that seems typical of Kallat’s ability to include humour in serious discussion, that image is set among a series of works that explore phantom-limb syndrome (in which amputees continue to have a sensation of pain apparently emanating from their missing limb), notably a replica of Indian-American neuroscientist Vilayanur S Ramachandran’s ‘mirror box’ by artist Alexa Wright. The mirror box is a device he created to treat patients suffering from phantom limb pain in order to give them the visual and psychological impression that they had two limbs so that they might regain control over the missing one. A theme that is given a more expansive treatment in Kader Attia’s wide-ranging film Reflecting Memory (2016). The format seemed much like the March Meeting’s – a series of interviews, with academics, historians and psychologists (the theorists), as well as surgeons and patients (the practitioners), exploring the experience and aftereffects of loss, here ranging from the loss of a limb to the loss experienced during the Holocaust. What emerges is a reflection on the complex workings and effects of memory, the responsibilities of memory and the psychology that goes with it. Or if you like, the importance of being able to tell your own stories.

Amid all that there’s a notable interview with American art-historian Huey Copeland, who discusses the extent to which a trauma can’t be real unless you have evidence for it. A visual sign. He is speaking in particular of images of plantation labourers in the US, often used to illustrate lectures on slavery. Most of them, he points out, were taken after the abolition of slavery. There is no shortage of evidence of the actuality of slavery, he suggests; we don’t need pictures to prove it. What the use of these images of plantation workers really demonstrates, Copeland suggests, is that we do need a visual sign to make something real. They tell us, then, not so much about our past, but about our contemporary psychology. And our need for those filims. Which, in a way, and alongside entanglement, is what Kallat’s show is about.

So what’s left? A world that’s inherently complex. One in which we have to negotiate a tangled web of the real and the imaginary that can only be grasped through a web of narratives and the moments at which they connect. Or almost connect. A world in which truth is hard to find. A world in which we have to act in much the same way as Spivak (channelling, as she acknowledges, Derrida) describes in the afterword to her translation of three of Mahasweta’s stories, under the title Impossible Maps (1995; the collection in which ‘Pterodactyl…’ appears): ‘Since the general tendency in reading and teaching so-called “Third World” literature is toward an uninstructed cultural relativism, I have always written companion essays with each of my translations, attempting to intervene and transform this tendency. I have, perhaps foolishly, attempted to open the structure of an impossible social justice glimpsed through remote and secret encounters with singular figures; to bear witness to the specificity of language, theme, and history as well as to supplement hegemonic notions of a hybrid global culture with the experience of an impossible social justice.’ If that sounds at once like a paradox, that’s because it is – the Gordian knot about which Mahasweta writes. But it’s in that leap from the specific to the impossible that art must and can carve out a space.

Tangled Hierarchy, curated by Jitish Kallat, is on view at John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, England, through 10 September; Mahasweta Devi’s Our Santiniketan (Seagull) is newly published in a translation by Radha Chakravarty